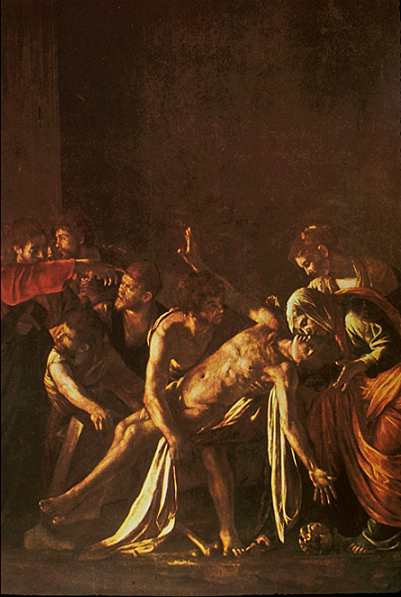

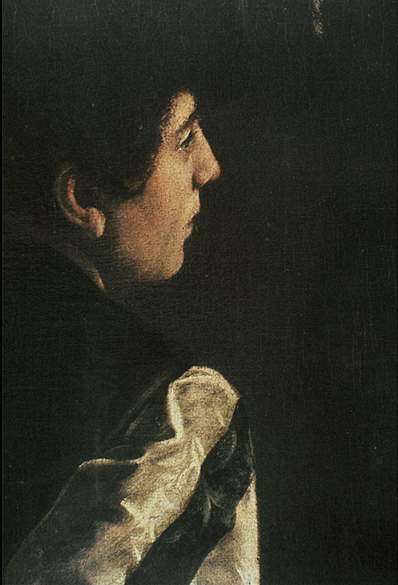

Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, Roma, San Luigi dei Francesi (the French church in Rome). Calling of Saint Matthew (detail), Roma.

Jacques-Edouard Berger's admiration for Caravaggio was boundless. In his role as professor of art history at the Lausanne Fine Arts College, he used this painter's oeuvre to initiate students to the realm of art. And on a study trip to Rome, the Caravaggio he presented to us "live" more than fully satisfied our newly awakened and enthusiastic scholarly expectations. Each subsequent lecture class cast new light on this great artist's oeuvre. On our way back from southern India, a surprise stopover in Rome gave us a few hours at San Luigi dei Francesi. By the time we had also indulged in a "tartuffe" (chocolate delicacy) at "Trescalini" on Piazza Navona, the magnificence of Caravaggio had made its way to our hearts on the same level as Shiva.

This approach to Caravaggio's work changed my way of living, seeing, thinking. My own zones of shadow and light unfolded, lending a dynamism to my life that, if not always easy to live with, developed into a not only exciting but, above all, vital new facet. The present Web program devoted to Caravaggio is my way of thanking Jacques-Edouard. The program texts and images are based on five of his lectures.

The painter is a medium, revealing - in the immensity of his consciousness - the very magma of our human quality, our strengths, weaknesses, the dark and light zones of our personality. To stand before a painting by Caravaggio is an experience that leaves an indelible mark. According to Berger, Caravaggio possessed a particularly vast range of knowledge - a wide span of feelings and possibilities, great self-knowledge and understanding of his fellow man; he was familiar with the laws governing human behavior, with good and evil. His extraordinary technical prowess enabled him to translate an overall grasp of life itself into a whole language, a new message. To see a Caravaggio is to allow our own vital space, as if by mirror effect, to start resonating, to open up onto this artist's visions and world. The experience provokes a revelation, an awakening to our own zones of light and darkness, a manner of participating in his rhythms, allowing time to flow at his tempo, travelling among vibrant blacks, allowing ourselves to be guided by a shaft of light. More still, a manner of breathing such light, of receiving Christ's vision through that of the artist. Caravaggio was endowed with a vast and deep-rooted understanding of all things human - the joys, the horrors, the cowardice, the tenderness, the gentleness of Man. In his empathy with life, and with death, all senses flayed, in the throes of a shriek, Caravaggio pulls us along beyond all that mires us down, to where redemption glimmers as a possible. He actually transposes us into such a state of receptivity that his message pierces us as forcefully as the light flashing from St. Matthew's eyes. Similar to the role played by the sculptor Unkei in Japanese Buddhist thought, Caravaggio is among the significant few to ferry Western painting and the message of Christ across the centuries. His works command our presence, inspiring the self-awareness necessary to open our minds and hearts to an adventure imbued with mysticism.

Line Chatelain

Madone du Magnificat, Botticelli

Botticelli's friend, Marsilio Ficino - a humanist, philosopher, and theorist - favored the Platonic method of attaining supreme beauty. In his Madonna of the Magnificat, for example, Botticelli had no need to reproduce a single face to depict his angels. In order to rival nature, he used the faces of several children or adolescents to reconstruct a perhaps impersonal, but nonetheless living, angel. An angel far more touching than the little rascals, with their dirty hands and impulsive gestures, who served as models to the painter and remained blissfully unaware of their own grace.

Botticelli's angels, built up out of memories and superposed layers of beauty, retain their whiteness, their meditative attitude, their silence: the five angels could be five dreams of the ideal adolescent.

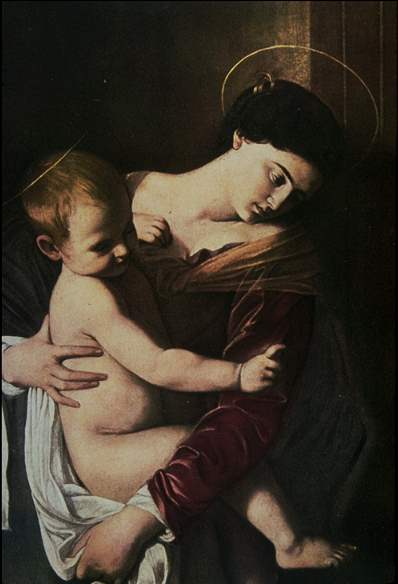

By contrast, Caravaggio was not inspired by utopia, by dreams. It was beyond his power to envision a saintly face such as depicted by a Botticelli or a Raphael. A madonna painted by Caravaggio - his Madonna of the Pilgrims (or Madonna of Loreto), for instance - had to come alive in flesh and blood, in her pain and suffering, in her light. Nor did Caravaggio invent his models, or even less, seek them out among the Roman nobility, flattering this or that daughter of a noble with the role of Lucretia or St. Anne. It was in lowly dives, in this or that inn, off the street that he sought them, a procedure that soon came to be considered as scandalous.

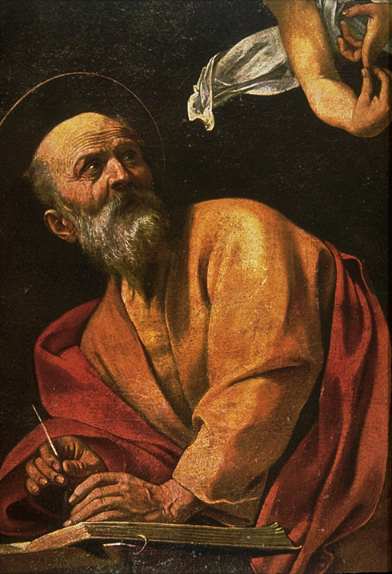

St. Matthew and the Angel, his first piece for the Contarelli Chapel (S. Luigi dei Francesi), in 1600, was removed on the day of the chapel's inauguration.

The man who had served as model for St. Matthew was one of the neighborhood's most ill-reputed drunkards: his black and neglected footnails in the foreground incurred such disapprobation that the painting had to be taken down immediately. Caravaggio set himself to the task of providing a second version. Death of the Virgin would be refused once the secret leaked out that the corpse of the Virgin was modelled on the corpse of a drowned girl pulled out from the Tiber.

Madone des Pélerins

Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, Roma, San Luigi dei Francesi (the French church in Rome). Calling of Saint Matthew (detail), Roma.

It is Caravaggio who invented "chiaroscuro" cast in the role of a work's principal dramatic agent. Other Italian painters who preceded him also attempted to portray night.

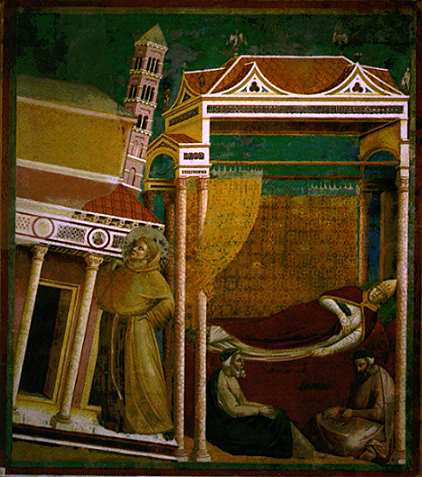

- Giotto at Assisi

Chronologically speaking, the first attempt is signed by Giotto. In the fresco cycle the Legend of St. Francis of Assisi, visitors to the basilica are struck by a painting of night: Innocent III's Dream

. In his dreams, the Pope is visited by St. Francis upholding the sagging church. How does Giotto depict night? He portrays the Pope stretched out on the bed of his bedroom, which is open in the manner of a stage setting. The scene is flooded with daylight, on the basis of a convention obeyed by this post-Medieval artist: only the fact that the Pope sleeps reveals that this is a night scene. - Piero della Francesca at Arezzo

The arrival of the Renaissance brought with it a growing search for verisimilitude. In his magnificent fresco series, the Story of the True Cross, Piero della Francesca attempts to portray night in the scene Constantine's Dream

. He does so by handling the scene in a camaïeu of grays, thus producing a monochrome effect of light that differs from Giotto's daylight. We do not yet find the light-and-dark effect that would suit this scene, which remains conventional. - Tintoretto in Venice

Night was increasingly portrayed during the surprising trend that followed upon the great age of the Renaissance, namely Mannerism (ca 1520 -1600). This school of thought focused on intellectual concerns and scholarly research. In such a spirit, the decors, atmospheres and particular incidents were left to the artists to decide.

Tintoretto painted the Adoration of the Three Wise Men as an open stage where we see the Holy Family, the Three Wise Men and the usual worshippers, bathed and highlighted by an already distinctive light provided by a tiny night light hanging a few meters above the scene. There is an attempt here to convey reality, natural details, light, but without transgressing medieval conventions. - Jacopo Zucchi

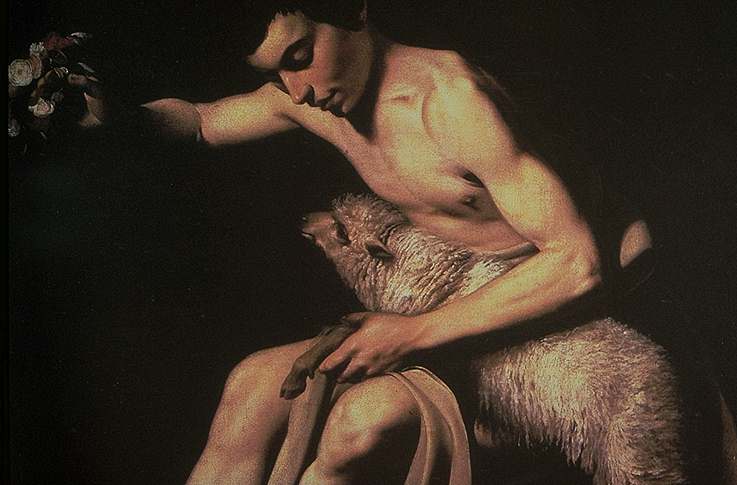

The consensus among art historians is that it was Jacop Zucchi who gave the world a first picture of night. His Psyche's Dream reveals an attempt, however modest, at distinguishing the zones of light and dark on the bodies of Psyché and Eros, to lend coherency to the depiction of night. - Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio John the Baptist,

, Bâle Kunstmuseum

Traditional representations of John the Baptist are of an adolescent, accompanied by a lamb, foreshadowing the Passion of Christ. But this portrait of him is a far cry from the Florentine and Roman High Renaissance portraits that make an ephebe of this saint, in Greek fashion. Here we have a 17th-century young man with obviously Italian features and a pallid complexion: the portrayal is forthright and eschews the idealism imposed on the plastic arts by prior generations, in particular with respect to pictorial language. This realist approach is a key concept for understanding Caravaggio's impact.

The most striking element of this painting is the light distribution. The background is plunged in total darkness. No trace of the setting is to be seen - no familiar objects or landscape or grotto situates this work in a defined site. It is as if a backdrop were stretched out behind the scene. The backdrop is in fact night - a deep brown night, almost black, where light brutally brings out the shoulder, leg, and profile of the adolescent, together with the body of the lamb. The technical name for painting using light effects is "chiaroscuro". It is Caravaggio who invented "chiaroscuro" cast in the role of a work's principal dramatic agent. Caravaggio, The Night Prince

In painting darkness and light, Caravaggio never worked mechanically. He had no interest in producing something new merely for the sake of novelty. His idea was to invent a new language, not in the cause of naturalism but in that of mysticism. Caravaggio renounced the epiphanies, the saintly icons multiplied by hundreds by the Mannerists; he was fed up with ascensions of the Virgin surrounded by angels and pink swirls. Caravaggio was a mystic, a believer whose faith was deep-rooted. His idea was to give Divine Will another mission, another instrument: light as the instrument of God's will. There is no light without shadow, no shadow without light. Caravaggio extricates man from shadow to bring him to light, and this light traces His message in the night. Caravaggio cannot be considered a realist painter, no matter how plebeian his models. The underlying aim is supernatural, spiritual. What lends life to anonymous creatures is the hand of God, as represented by a shaft of light that falls on the Chosen One.

This painter's orchestration of his compositions transforms the play of light and dark into a vital dynamic agent. The human body thus loses the basic role attributed to it by the Renaissance: in Caravaggio's work, light serves as a signifier. It traces reality, underscores and exalts it, serving principally to create dialogue between the figures, a dialogue of gazes. Light defines the relationship between the figures portrayed. The light sought out is a light born out of nowhere, a revelation of divine origin. Beyond the genre scenes and the chiaroscuro technique, the resulting oeuvre is imbued with mysticism. This light of divine origin traces reality, but also helps us to understand such reality. Nonetheless, this oeuvre cannot be labelled realist: indeed, he was attacked by art critics because "He does not know how to observe reality". For Caravaggio, the mission was to create a miracle, to reveal the hand of God.

29 September 1571: Michelangle Merisi is born in Caravaggio. His father, Fermo, is both architect and majordomo to Francesco Sforza, the Marquis of Caravaggio :

- 1584:

- at 13, he is apprenticed for four years to Simone Perterzano in Milan;

- having completed his apprenticeship, he works a few years probably in Milan or elsewhere in Lombard. - 1592:

- arrival in Rome at 21 - he works for Cavaliere d'Arpino

- leads an extremely frugal existence

- meets Valentin, an art dealer located near S. Luigi dei Francesi

- introduced to Cardinal del Monte - 1593:

- Boy Bitten by a Lizard

- takes up lodgings at the Cardinal's residence, receiving room, board, and a salary

- The Fortune-teller

- Basket of Fruit

- last secular works. - 1597, as of this year, Caravaggio devotes himself exclusively to religious paintings.

- 1598: receives a commission for 3 paintings for the Contarelli Chapel (S. Luigi dei Francesi) in Rome, illustrating the life of Saint Matthew

- 7 February 1600: complaint lodged against him for assault and battery against Flavio Canonico, sergeant at the Château Saint-Ange

- 19 November 1600: complaint lodged against him for assault and battery against the painter G. Spamba da Montepulciano

- 12 October 1604: denounced for throwing stones at the night watch, via del Babuino

- 1604: the painting Entombment

- 12 mai 1605:

- arrested for illegal carrying of firearms - 10 juillet 1605:

- imprisoned in Tor di Nonna for a womanizing episode. - 1605:

- during a "four to four" brawl, he kills Ranuccio Tammasoni da Terni.

- flees Rome for Palestrina, to the home of Prince M. Clonna, the Marquis da Caravaggio's brother-in-law.

- paints Death of the Virgin

- 1607:

- paints Seven Works of Mercy

- 1608:

- goes from Naples to Malta, where "he has good customers": the Knights of the Order of St. John.

- paints Beheading of St. John the Baptist

- 6 October: alerted by rumors from Rome, the knights carry out an investigation of Caravaggio; summoned to appear before the Order, he is expelled from their ranks and driven out of Malta on December 1.

- he reappears in Sicily, Syracuse, Messina, and Palermo. - 1609:

- the clergy of the Crociferi Church in Messina records the acquisition of the Raising of Lazarus

- Caravaggio reappears in Naples, where he is gravely wounded upon leaving the Cerriglio tavern. - juillet 1610:

- informed of his imminent pardon, Caravaggio sails off to Porto Ercole (Spanish enclave on Tuscan coast); he crosses over the boundary of the Papal States, where he is arrested and then released

- as narrated by Baglione in his chronicles of the period: "Once released, he could no longer find the felucca. Furious and desperate, he ran up and down the beach, sweltering under the sun and scanning the horizon for the boat carrying off all his meager belongings. At noon he suffered a fever attack and lay down. Without any human assistance, over almost three days, he died as he had lived, miserably. It was July 18th. In Rome, his pardon had been granted the day before!"

- A genius in all he created

- Leading a life of debauchery, drinking, and brawls

- Womanizer

- A murderer

- An exile, a wanderer, a solitary figure

- Revolutionary in everything he undertook

- A romantic figure before his time

- figure romantique avant l'heure

- Karl von Mandel, Giulio Mancini, Giovanni Baglion, exegetes of this artist, paint a black picture of Caravaggio as a social misfit with a turbulent and provocative character.

- Bellori: "His temperament encouraged his dark side, to match his turbulent and provocative nature."

- Poussin: Poussin: "He destroyed the art of painting."

- Cardinal del Monte: "He had as much trouble painting flowers as figures, since he lacked any preconceived distinction between the beautiful and the ugly, the noble and the base."

- It was not until the Milan exhibition of 1951 that, at last, this artist's oeuvre came to reveal the complexity of his personality:

- It became clear above all that he was intensely a product of his times;

- He was born in the year of the massacre on St Bartholomew's Day in Paris;

- He died in the year of the assassination of Henry IV.

I - The miraculous Caravaggio

Caravaggio's life during the 17th century is certainly among the most adventurous ever led by the world's great creators.

His life story takes place between shadow and light: a man of a passionate nature, he ran the gamut from provocation to murder. A reward was offered for his capture, sending him into perpetual flight and hiding. Yet none of this transpires in his oeuvre, which is doubtlessly the most profoundly fervent oeuvre in all of Baroque painting. This is the miracle of Caravaggio, the miracle of the sacred portrayed in dimensions he alone mastered.

II- Peterzano's workshop

Michelangelo Merisi was born on September 29, 1571, in the little village of Caravaggio in northern Italy. He was named after his birthplace, a procedure not unusual for the times. Enjoying a double status as both architect and majordomo to the Marquis of Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi's father was firmly ensconced in that noble household. The Marquis, a patron in the Renaissance tradition, had several artists at his beck and call. This tradition was quite common: Raphael, for instance, was also majordomo to the pope, as well as the latter's antique dealer, archaeologist, in addition to being in his employ as a painter. All too often, 19th-century art historians have portrayed Caravaggio as being of humble origin, when in fact, he came from an excellent family of artists. A family, moreover, whose social welfare was in the hands of an excellent marquis, who, in turn, considered himself a patron in the spirit of the 15th century rather than his own 16th.As was the fashion, Caravaggio began studying painting at an early age. Indeed, Renaissance and Baroque painters were often destined from birth to be artists, so that already during earliest childhood they learned how to grind pigments. Hence, as young adults, they knew their profession inside out. When Caravaggio was 13, the family decided he would devote himself to painting. He was sent to the painter Peterzano's studio, one of the good studios in Milan. "Good" in the sense that, because Peterzano himself was a poor painter, his apprentices had ample occasion to learn. Unlike talented painters, who tend to impose their vision of the art onto their pupils, the poor painter has nothing to impose. This allows his pupils to blossom out on their own, and to achieve a personal vision. Certainly, a poor pupil will become a poor painter, but the geniuses will accomplish their apprenticeship without suffering damage or influence, and having gained a command of the technique involved. This is the sort of education Caravaggio received.

III-

A life of misery

In 1592, Caravaggio arrived in Rome. Obviously, he would have been better off fulfilling some important local commissions first, so as to have a letter of recommendation from someone important, and to arrive in Rome at a more mature moment of his career.

But Caravaggio decided to settle in Rome immediately, at the age of 21: the age of his first paintings. Unsurprisingly, these met with little success. Rome was crawling with painters, ornamental decorators. Who needed this young man, an unbearable person on top of it all? Someone who openly professed to find the painting being done by his peers unacceptable, who was not impressed by the recognized masterpieces, who boasted he could do better than other artists. The life of misery that stretched out before him seemed romantic during his first years in Rome. A recommendation from his venerable master Peterzano won him employ with the Mannerist painter Giuseppe Caesare, also known as Cavaliere d'Arpino, an even less talented painter than Peterzano, but endowed with two features that were keys to his success: he worked dressed to the hilt, complete with lace cuffs and a sword at his side, and he worked at an incredible speed: two hours for a Saint Cecilia! Cardinals travelled from far and wide to see this phenomenon, as if off to a fair. Cavaliere d'Arpino took advantage of Caravaggio, obliging him to do all the boring work - the flower wreaths, the mascarons, the caryatids - and not paying him a cent for any of it. Caravaggio was totally destitute; rumor has it that he did portraits of the innkeepers to eke out a livelihood. Stealing to eat, squatting to sleep. But he did get lucky. One night, at Piazza Navona, the artist's district, he met a singular person, half French and half Italian, who went by the name of Valentin. Now this Valentin had a brilliant idea: the people who want to buy pictures are people with high-flown names and expensive clothes, and therefore loathe to come into contact with the dusty studios of artists. Why not use an elegant apartment, nicely furnished, where the work of a young painter could be put on display for contemplation by potential patrons? Valentin had invented the art gallery!

Among his first victims - for, obviously, he picked up the paintings for a song and then resold them at high prices - was the young Caravaggio, from whom Valentin commissioned light and charming subjects, sweet and gentle, nothing too brazen, of the sort so popular at the time.

IV- An enlightened patron

In this fashion, with Valentin as middleman, Caravaggio developed quite a substantial clientele. His customers included a certain Cardinal Del Monte, an enterprising individual said to be the most boring of prelates, but the most well-informed of art lovers. The Cardinal lured Caravaggio away from Valentin's stable of artists, offering him room, board, and a salary. But just when everything was going so well for this artist, comfortably installed under the wing of a generous patron, Caravaggio's passionate nature got the better of him and he began acting in most unruly manner. The first "scandal" dates to 1600. Of course, we art historians tend to speak of the greats as impassioned by their art, to which they devoted themselves day and night. But the truth of the matter is that Caravaggio was a drinker, a womanizer, a pugnacious individual who frequently ended up at the police station.V- An

excessive and violent temperament

Caravaggio's life was spent in permanent exile. He was obliged to flee Rome, despite the protection of the Cardinals Del Monte and Scipion Borghese. Murder had taken place. Bellori narrates: "Caravaggio, although occupied by his painting, still found time to keep up his troublemaking. After spending several hours of the day at his painting, he would swagger along the city streets, with a sword at his side, clearly proving he had other interests beyond his art."

In one brawl in the midst of playing a game of racquets (royal tennis), he ended up stabbing and killing his young opponent, sustaining some injury himself in the process. Numerous documents testify to the fact that Caravaggio killed Ranuccio Tomassoni da Terni on the Campo di Marzo, May 6, 1606.

He fled Rome, penniless and barely out of pursuit's reach; he found sanctuary in Zagarolo, under the protection of Duke Don Marzio Colonna, for whom he painted a Christ at Emmaus and and a half-length portrait of Mary Magdalene, works since lost. He next set off for Naples, where, having already made something of an artistic reputation for himself, he received several commissions. But his behavior kept getting worse, and he again committed murder - not once, but three times. Caravaggio had become a murderer. His life was fraught with danger despite attempts at his protection, and would, from then on, be spent in constant flight.

VI- A destroyer of the art of painting

SCaravaggio's delinquency lent credence to the criticism directed against his art: he had numerous detractors, from countless sources. Indignant and offended voices rose in clamororous disapproval. Among the most disparaging of his critics was Nicolas Poussin who, at the time, lorded over a coterie enthused by the sort of classicism for which Poussin himself was the high priest: a clear sense of proportions and calm. Contemplating Caravaggio's Death of the Virgin

Death of the Virgin" created a scandal. It was common knowledge that the artist had killed, that his soul was black, and that therefore his painting would be black. This painting in particular instigated all the debate over Caravaggio's verism. The Virgin is truly dead. Her body shows the marks of her death

, Poussin began to scream, shouting angrily: "I won't look at it, it's disgusting. That man was born to destroy the art of painting. Such a vulgar painting can only be the work of a vulgar man. The ugliness of his paintings will lead him to hell." Stinging criticism that would take much time to subside. For two centuries, Caravaggio's work lay forgotten, and it was not until the Milan exhibition of 1951, that his oeuvre went on display to a public at last become aware of the depth of artistry involved.

VII-

Enthusiastic admirers

Caravaggio's scandalous reputation earned not only wails of disapproval, but also cries of admiration, of unbridled enthusiasm. Baglione, the somewhat mannered chronicler of pre-Baroque Rome, asserts: "A head by his hand was more expensive than a large-scale composition by his rivals, so great was the public favor in which he basked." To which Baglione could not refrain from adding: "...public favor that judged with its ears rather than its eyes."

The admiration of the "pro-Caravaggio clique" painstakingly fostered by Cardinal Del Monte was sincere. Young painters made a point of paying visit to the artist. Navigating between admirers and critics, Caravaggio endeavored to carve out a career for himself. As much a man as a painter, his impassioned and quick-tempered nature unfortunately corroborated the appalled observations spread by his detractors.

VIII- A promising start

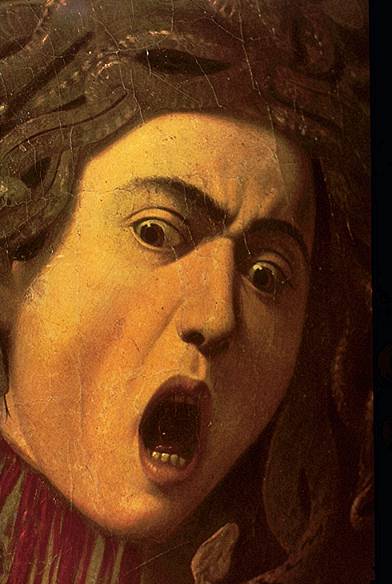

Commissioned to paint the ceremonial shield for an armor destined for the Grand Duke of Toscany, Caravaggio depicted a Medusa Head (detail)

Medusa Head, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi

Caravaggio's first self-portrait as an adolescent. One of this artist's first know works seems to have been a private commission by the Cardinal del Monte (according to Bellori), a Roman aristocrat, as a gift to the Grand Duke of Tuscany. The preceding era, which was Mannerist, had enjoyed spectacles. The 17th century would continue to wax enthusiastic, as is testified by the "carousels" (exhibitions or tournaments for horsemen) organized by Louis XVI at Versailles. The same sort of carousels took place in Florence as well. Extravagantsuits of armor and costumes were created for these equestrian shows, so that the spectators could feast their eyes on all the luxury and magnificence. For the Grand Duke of Tuscany, disguised as Perseus, a shield decorated with the head of Medusa was commissioned. The head was made of raging snakes. It is Baglione who recognized in this Medusa headthe first self-portrait

exuding violence and passion. His was the first Medusa head to inspire fear.

Caravaggio's early works were secular. At the time, the public was tired of all the grand mythological and allegorically pietist scenes typical of the late Mannerist period. Art lovers were attracted to restful works. To meet this new demand, artists began working in a pre-Rousseau style, implying a return to fresh and truthful feelings. Valentin excelled at selling this sort of "genre painting". Caravaggio's contributions were:

- Boy with Fruit Basket

Boy with Fruit Basket, Rome, Galleria Borghese

- Boy Bitten by a Lizard

Boy Bitten by a Lizard, London, National Gallery

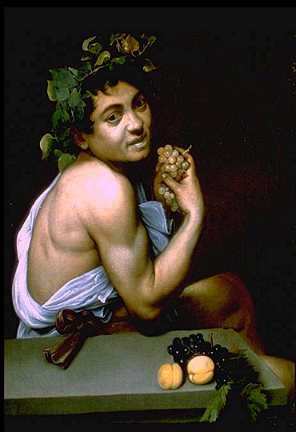

These were small paintings ("tableautins") suitable for the period habit of filling in the spaces between large-scale mythical works with such small pictures, turning picture walls into a frame-to-frame mosaics. Caravaggio's works fit right in with this fashion. Bacchus.

Bacchus, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi

This painting is what we can probably label as the first real "Caravaggio". His earlier works followed a relatively easy traditional format, executed rather dryly. But then he began seeking his models along the river banks, among the dregs of Roman society. With a subject such as Bacchus, the public felt uncomfortable with his choice. They felt even more ill at ease when it came to his use of such models to portray Jesus. An important point here is that Caravaggio repudiated what was considered good form at a time in his life when he could hardly allow himself to do so. To get his career underway, he should first have provided what was in demand, works in keeping with the taste of his times, and have waited until later before introducing inventions of his own. But this he refused, and his refusal turned each work he produced into a revolution. The results were a far cry from genre painting; rather, his painting represented a play on genre painting, underscored in each new work in an ever more brutal and impassioned manner. Finally, he asked Valentin to free him of the obligation of producing works on genre subjects. The real Caravaggio was in the process of being born, and Valentin, realizing this, asked for ever more works of the sort. In a fit of resentment, Caravaggio provided Sick Little Bacchus.

Sick Little Bacchus, Rome, Galleria Borghese, ca. 1593

IX- Compositions on a vaster scale

Michelangelo Merisi began replacing the solitary figures produced during his years of apprenticeship by compositions on a vaster scale. He created works with two, even three, figures, but still focusing on subjects light in spirit: The Fortune-teller

La Diseuse de bonne aventure, Paris, Musèe du Louvre

- the fact that the two figures are cut into half-lengths (instead of the more familiar full-length portraits)

- the fact of isolating the two figures (instead of the more familiar background landscapes showing off the artist's talent)

- the simplicity, i.e. vulgarity, of the setting - a plain whitewashed wall

- the unrealistic source of light

- strangely accented diagonal lines of force, coming from nowhere and heading nowhere

- the illogical positioning of the window. Critics noted: "He does not know how to observe reality."In point of fact, this is the first time that Caravaggio uses light as a signifier. Light here traces reality, underscores it, even exalts it. The shaft of light basically serves to create a dialogue between the two figures, a dialogue between two gazes. It defines the relationship between the two figures.

. At this point in his career, Caravaggio set out, at first quite discreetly, on what would be a lifelong quest: the search for light that, born from nowhere, represents a revelation of divine origin. His oeuvre outstripped genre painting or even pure chiaroscuro painting, gradually turning into the most mystical painting possible by the hand of man. The light in his oeuvre, taking its source in the divine, not only portrays reality but helps us understand the reality being depicted. Basket of Fruit

Basket of Fruit, Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana

, Narcissus

. Clearly, between his first genre painting and what we now see, the artist's intention had changed. The subject matter is new, reality is apprehended differently. Nonetheless, there remains a certain charm linked to paintings of genre subjects. Caravaggio would lose no time in erasing such facile seductions, turning out works less and less "pleasing" in the real sense of the word. These works would have fewer and fewer touches of bravado for bravado's sake, would come to depict the essence of their subject. Caravaggio did not remain an industrious artist-toiler in the pay of a gallery dealer, but became the protegé of a cardinal. This would lead the artist to religious paintings.

X- Profoundly mystical painting devoted to religion

Rest During the Flight into Egypt

Rest During the Flight into Egypt, Rome, Galleria Doria-Pamphili

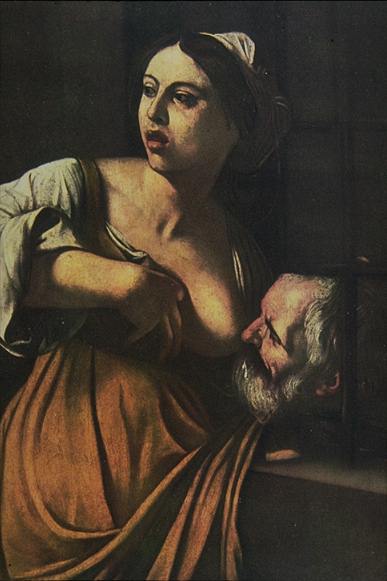

, Judith Beheading Holofernes.

Judith Beheading Holofernes, Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte antica, Palazzo Barberini

The amazing servant

, his impressive scar, and the horrible gaze of the old woman, Judith's impassive beauty provides a striking contrast reminiscent of the contrast between the angel and Joseph in "Rest During the Flight into Egypt". The beautiful head of Judith

The artist tried out several approaches: a bucolic approach in "Rest During the Flight into Egypt", expressionism in "Judith Beheading Holofernes". Here, in Repentant Magdalene (detail)

Penitent Magdalene, Rome, Galleria Doria-Pamphil

The subject was typical of the age of the Counter-Reformation. A richly dressed sinner abandons the very finery of her sins: her jewelry. She has broken them and set them aside to the left of the picture, thus composing a sublime still life, a "Vanitas". To the intoxication of wine, she prefers meditation, drawing near to God, as a new form of intoxication. She has shut herself off from the world in a deeply meditative stance, forming a marvelous ovoid, or fetal, shape, brought to life by the strange light that bathes her. Magdalene is preparing her rebirth; by the same token, both she and Caravaggio are being born to the world.

A detail of this marvelous painting...the gold chain...the string of pearls ... an earring that, strangely enough, reappears in almost all this artist's works, like some sort of occult signature. Baglione commented - somewhat nastily - that Caravaggio painted the flask of wine in order to prove to his customers that he had lost none of his painterly skills. The light that shines within the wine heightens its appeal, thus showing even more clearly how difficult it was for Magdalene to give it up.

, he affects a certain pietism, taking a classical approach to the subject of meditation and, in so doing, discovering his vocation. Caravaggio would paint the great mysteries of our faith, for he himself, deep down, was a believer. But he would do a great deal of soul searching in the process. Saint Catherine of Alexandria

Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Madrid, Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

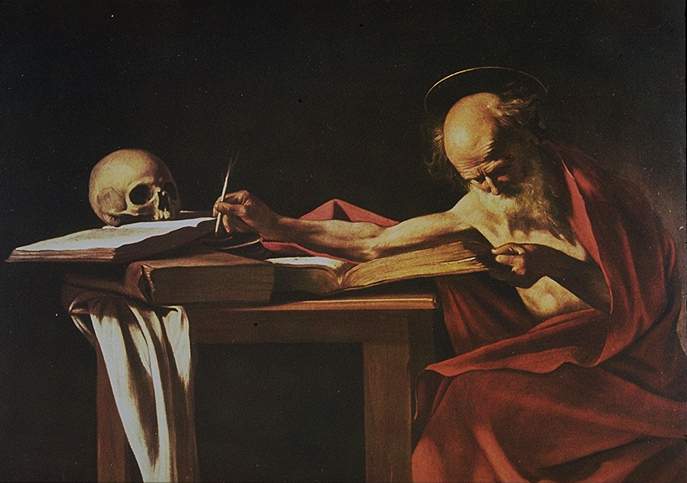

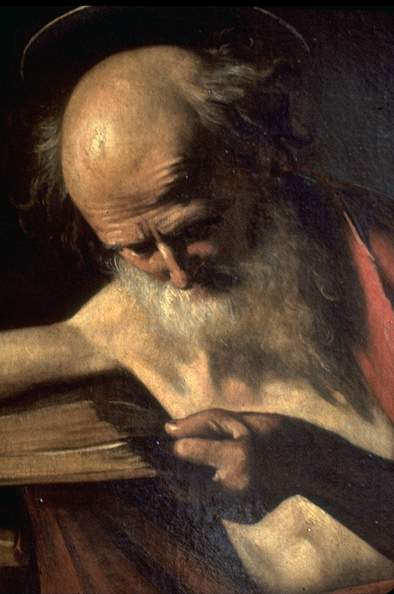

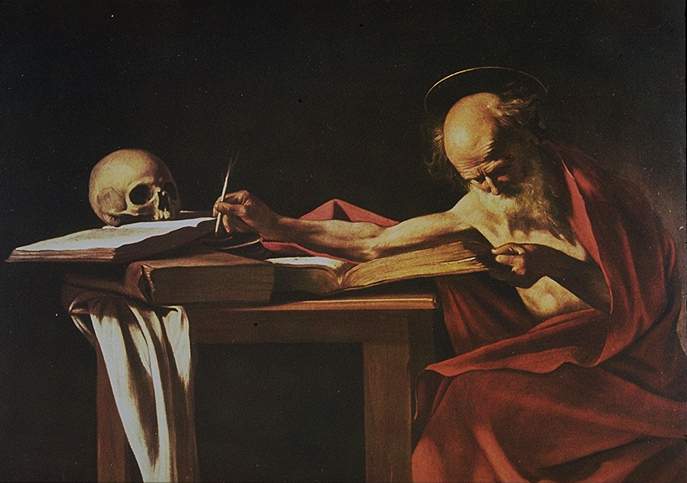

Saint Jerome, Rome, Galleria Borghese

Notice how both strain towards each other:

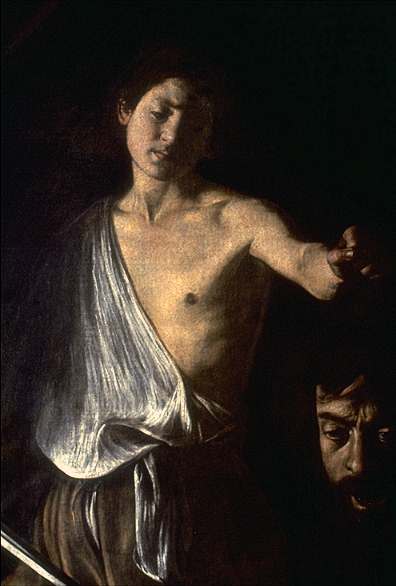

The theme itself was very popular during this artist's era, and was generally portrayed in grandiloquent fashion, mostly in pale pinks and blues, to match the taste of the day. Striving to transform mannerism into reality, here is what Caravaggio did with the theme: David with the Head of Goliath

David with Head of Goliath,Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

. The second version David with the Head of Goliath

David and Goliath, Rome, Galleria Borghese

Goliath

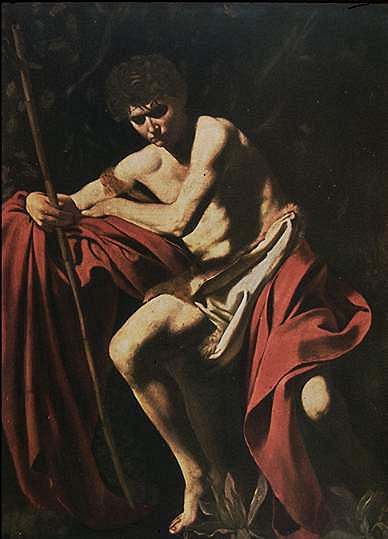

is absolutely hallucinatory. Thus it was through repetition of a subject - a subject vigorously pursued, scrutinized, and analyzed - that Caravaggio learned to bring out the most in himself as a painter. One of his favorite subjects was St. John the Baptist: whom he portrayed five times

- Saint John the Baptist, Rome, Musei Capitolini A St. John the Baptist

- Saint John the Baptist, Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Corsini A man in the street.St. John the Baptist is portrayed as older here, a man in the street, whose facial features bespeak a closed and commonplace mind. The round neckline of his attire reveals traces of a tan. This version was found to be shocking at the time.

- Saint John the Baptist, Rome, Galleria Borghese.An ambiguous portrait

- Saint John the Baptist, Kansas City, W. Rockhill Nelson Gallery of ArtSculpted out of shadow and light

- Saint John the Baptist

, each time seeking to outdo the last. Madonna of the Pilgrims

Madonna of Loreto, or Madonna of the Pilgrims, Rome, Sant'Agostino Church

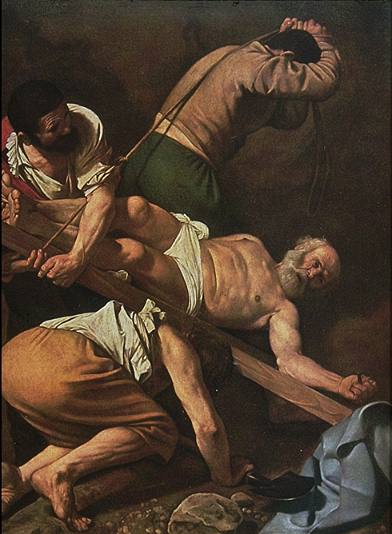

or the Madonna of Loreto. Although notorious for drinking, stealing, raping, looting, and murdering, Caravaggio continued to paint through thick and thin. Martyrdom of Saint Peter

Crucifixion of Saint Peter, Rome, Santa Maria del Popolo Church

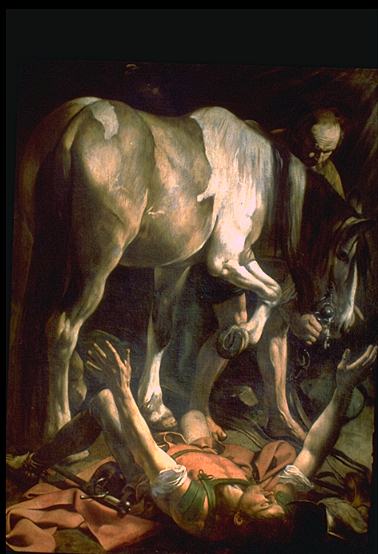

, Conversion of Saint Paul

Conversion of Saint Paul, Rome, Santa Maria del Popolo Church

Paul was a guardian-priest of the temple of Jerusalem, an originally Jewish city practicing the persecution of the early Christians. On the road to Damascus, Paul was struck by the divine light. Caravaggio succeeds in creating the illusion of a miracle, for it is a miraculous light that falls upon Paul. Where does it come from? From the phophorescent lighting of the horse's belly? The divine light breaks over the horse to better illuminate the figure on the ground. Just as in the painting of Magdalene, the composition closes into an ovoid shape, underscored by St. Paul's arms. We meet up again with the egg symbol here, and the idea of the rebirth of the primitive Christian tradition.

.

XI-L'exil

Entombment,

Entombment, Rome, Pinacoteca Vatican

Caravaggio had kept on painting during the days preceding the murder he was about to commit: near Cardinal del Monte's residence, a brawl of four against four took place over a game of racquets (royal tennis). Backed by Onorio Longo and Captain Antonio Bolognese, Caravaggio himself was wounded, but managed to kill Ranuccio Tommasoni de Terni ("Avvisi" di Roma, 31 May 1606). Hence, no sooner had commissions began pouring in than he was obliged to flee Rome. He found refuge in Palestrina, with Prince Marzio Collona, brother-in-law of Marquis di Caravaggio. October 6th found him in Naples, facing a long period of exile. Here he had to start all over again, but it was for this very reason - deprived as he was of all security, roots, and official protection - that he would produce his most overpowering paintings. What came at this point in his career surpassed all he had accomplished before.

The chronicler Babioni indicates that Caravaggio painted this work very quickly during his time of exile in Palestrina, in order to earn the price of his fare to Naples.

Madonna of the Rosary

Madonna of the Rosary, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

, Seven Works of Mercy

Seven Works of Mercy, Naples, Pio Monte della Misericordia Church

. We have, so far, mentioned the main stages in this painter's career: Milan, Rome, Naples. For the usual reasons, he subsequently was obliged to flee Naples; he set sail for Malta, where he became painter for the Grand Master of the Order of St. John who, it is said, admitted the artist to the Order. Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt

Musée du Louvre - Paris

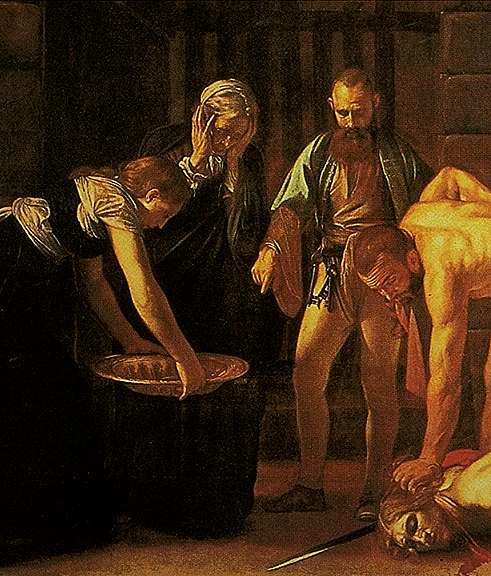

, Caravaggio's art was now at its zenith. While living peacefully on the island of Malta, under the protection of the Knights of the Order of St. John, he painted one of the most moving portrayals of John the Baptist ever achieved: The Beheading of St. John the Baptist

Beheading of St. John the Baptist, La Vallette (Malta), Cathedral St. John

, for the Cathedral of Valette. The rather worn theme of Salome and this saint, the dialogue between the woman and the severed head, attracted painters from the first primitives of the Roman era on through until Lucas Cranach (1472-1553) of the Mannerist period, but never before had the subject been handled at once so supremely and so damnably. As chronicled by Baglione, Caravaggio - having gravely offended one of the knights - was imprisoned, managed to escape and flee from Malta. He reached Sicily and settled in Palermo, from where he travelled for temporary stays in Messina and Syracuse.

Raising of Lazarus

Raising of Lazarus, Messina, Museo Regionale, 1609

, Adoration of the Shepherds

Adoration of the Shepherds, Messina, Museo Regionale

. The rumor of his imminent pardon reached Caravaggio. We have followed this artist from site to site and stage to stage, discovering an artist ever more imbued with the religious mystery he so masterfully painted and so fervently conveyed.

Indeed, the works he produced were so deeply mystical and essential, testifying to such a true sense of the sacred and, above all, such a heartfelt comprehension of the message of Christianity, that the Roman people were ready to forgive Caravaggio all. In a happy frame of mind, the artist set off for Naples without remembering to officially declare himself a passenger. In other words, he became a stowaway, and, in order to ensure his fare, was obliged to hand over his possessions as security. This was something he was not prepared to do and, stupidly attacking one of the sailors, he brought down upon himself the wrath of the entire crew. Wounded, he left the ship at Porto Ercole where, furious and desperate, he ran up and down the beach under a scorching sun, trying to pinpoint on the vast sea the vessel sailing off with his belongings. By noon, fever forced him to lie down and there, after three days, without the least human assistance, he died in the same fashion as he had lived his life, namely all alone. This took place on July 18th.

Historical context

Happenstance granted Caravaggio his first major commission, in 1598. Matthieu Cointrel (a Frenchman whose name became Italianized as Matteo Contarelli), who became cardinal under Pope Gregory XIII, was having the Church of S. Luigi Dei Francesi rebuilt, and the Contarelli Chapel added to it. Muziano and Cavaliere d'Arpino (Giuseppe Cesari, late Italian Mannerist painter) worked on this renovation, but in the meantime Matteo Contarelli passed away. The person appointed to execute the latter's will, a certain Virgilio Crescenzi, was put in charge of the project's continuation. In 1596, feeling the project had been too greatly slowed down, the clergy of S. Luigi dei Francesi expressed their annoyance to the Pope. The Pope replied by contacting Crescenzi, asking that things be speeded up and, upon the recommendation of Cardinal del Monte, commissioning Caravaggio to provide three paintings for the chapel.The cycle inaugurated in 1601 caused such a scandal that one panel was totally refused. These three works, based on the life of St. Matthew, in themselves summarize Caravaggio's entire output: the painter in all his facets is present in the Contarelli chapel.

First, however, let us consider two major trademark features of the Caravaggio "revolution":

- This painter's orchestration of his compositions transforms the play of light and dark into a vital dynamic agent. The human body thus loses the basic role attributed to it by the Renaissance.

- His approach repudiated the Mannerist trend which featured a multiplicity of exaggerated and sophisticated formulas in order to escape the overly rigid aesthetic values of the Renaissance. In fact, the Mannerist artists succeeded only in multiplying certain constraints, while Caravaggio dared to cut all ties to the past.

St. Matthew and the Angel

Matthew is shown as he counts his earnings, while awaiting the ferry boat. The scene takes place in a sulfurous atmosphere where the only scenic elements are a table bearing the coins being counted by a young man. A usurer stands by the youth's side to keep track of his countings. Two ornately-dressed young men cast a distracted look to the side, where two figures are entering the room. An arm stetches out towards Matthew, and one hears: "You are Matthew, Matthew you will follow me." The outstretched hand is repeated in Matthew's raised hand. Two hands: one serves to designate, and the other to reply to the designation. Nothing more. The miraculous aspect of this painting is that something is actually in the process of happening: Christ has just walked in and designated Matthew. Light precedes, follows, and accompanies Christ's arm. The two have come to an understanding. There is nothing obvious about the miracle here, for Caravaggio wanted it to be subtle. The first person entering - St. Peter - hides the Christ figure, while the young men hide the figure Matthew; and yet, gaze meets hand. The miracle here lies in the chiaroscuro. The miracle by Caravaggio.

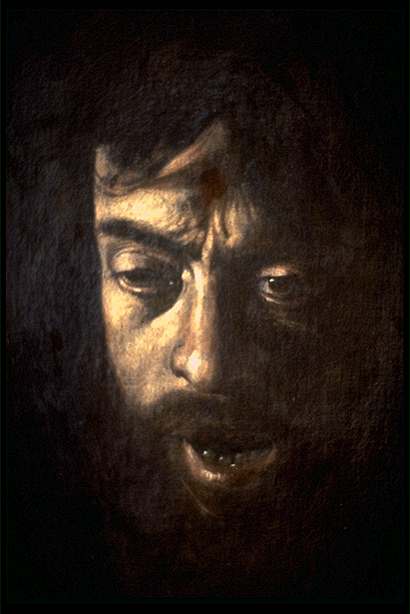

No one could know it was Christ who was entering the room: he is shown entering without fanfare, mingling in with an everyday reality that continues. Matthew's face

is transfigured; it is a handsome face with bright eyes, lips curled into almost a smile. He feels truly designated. As for the Christ

figure, we search the composition to find it and, when we do, we are struck by the way it emanates an at once sacred and altogether human fervor. It is among the most religiously persuasive and generous portrayals of Christ in all of Western painting, miraculously conveying the goodness, openspirit, and light of His gaze. How ironic that this man, notorious for the debauchery of his life,should be able to paint the truths of humanity and the generosity of Christ better than anyone else. In his comprehension of Christ, Caravaggio is on a par with the great mystics of all time. Before this painter, no one had ever managed to depict the calling of St. Matthew in terms so faithful to the Scripture. As is only natural, certain figures block the revelation being made, and these do not belong to the central mystery. The young man

in the foreground

turns his head, for he has heard a noise. His companion casts an astonishingly empty look at the newcomer. The gazes of the two well-dressed young men conceal the meaningful gazes of Matthew and Christ. Christ's eyes are the eyes of Matthew, and Matthew's eyes

breathe the light of the eyes of Christ.

.

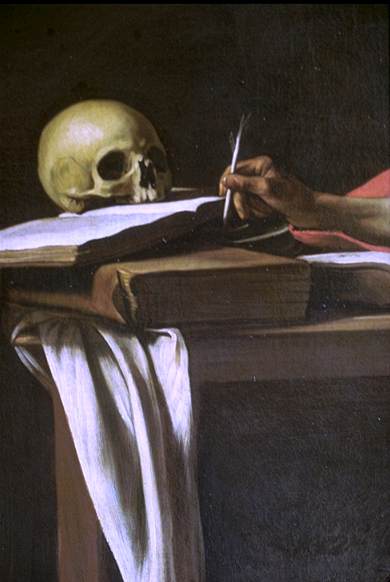

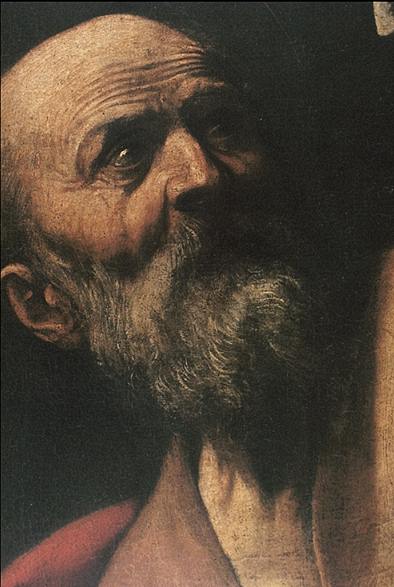

St. Matthew and the Angel

The angel who inspires him matches Matthew, for this is no literary angel, but an angel for ferrymen.

Has anyone ever painted such an unsaintly St. Matthew, such an unangelic angel? Matthew earned his living as a ferryman; he was no literary or scientific figure. He wrote his Gospel without any Ph.D.; indeed, he looks as if writing does not come easily to him. Caravaggio applied himself to convey the thickness of Matthew's joints, the heaviness of his hands, the weight of his shoulders, his "squirming" at the writing table.

Matthew's hands are rough and calloused, as if he hardly could be expected to hold a quill

. The angel who inspires

him matches Matthieu

. The angel even has a ferryman's face! Despite Matthew's clumsiness, we can see his good will. The swirling nature of the angel is all the more miraculous, for he brings the revelation of the Word to someone attempting to write. The dialogue comes alive with immense tenderness, with intensely emotional and fervent feeling. Matthew's face

, with its coarse skin and wild beard, lights up and casts a gaze of thankfulness towards the angel.

Martyre de Saint Matthieu

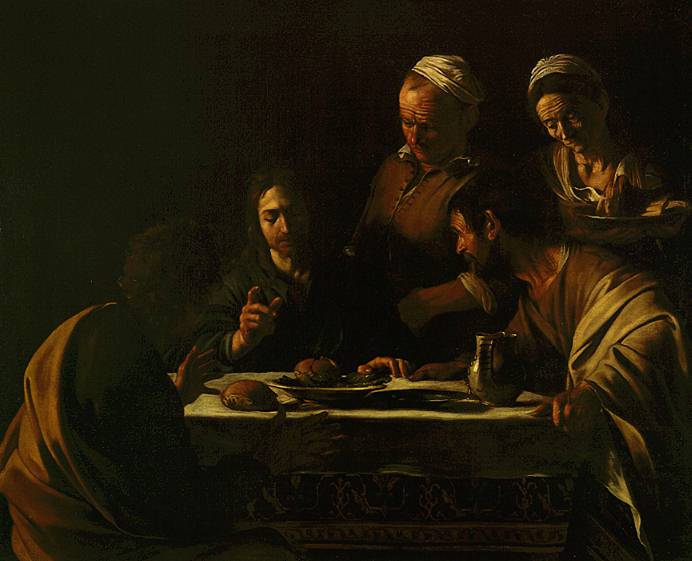

Supper at Emmaus, London, National Gallery.

Light is used for dramatic effect. The food set out on the table shows that Caravaggio still enjoyed doing still lifes. Here, the crisply roasted chicken, the roll, the crumbs, the basket of fruit all participate in the artist's staging of a still life, his staging of colors. The red of Christ's robe matches the duller red of the innkeeper's tunic. Light is used for dramatic effect here: Christ's shadow is transformed into a halo in the negative in a manner that underscores this figure in the midst of the composition.

Supper at Emmaus, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera

All trace of painterly self-indulgence has been erased. Caravaggio took up this subject again in 1610, the year of his death. We see the same Christ, the same table, same still life, same associates. But this version is in an entitely different register. The table, built up out of horizontals, is handled anamorphically All trace of painterly self-indulgence has been erased with respect to what is shown on the table and the expressions on the various faces. The camieu (form of 'grisaille' of a single color but in varied tones) runs from olive green to sand, in a whole range of tones, including black. Nothing is added for effect. The only color is the bluish gray of Christ's robe. The economy of means found in this painting prepares the way for Caravaggism: it comprises all that the young Velasquez, Zurburan, George de la Tour, Le Nain, or Vermeer would take up. Interestingly, Vermeer and Caravaggio both knew exactly how to make a camaieu of grays using a bright blue. One wonders whether Vermeer ever caught a glimpse of this painting?

David avec la tête de Goliath, Vienne, Kunsthistorisches Museum.

A sibylic gaze, the gaze of a prophet. Illuminated by a shaft of supernatural light, David steps out from the night, his expression emptied of all content by a divine vision. He casts about a sibylic gaze, the gaze of a prophet. Holding the enormous and very human head of Goliath in his hand, David himself seems to be holding death in abeyance. Goliath seems on the verge of howling with anger and rage. Both faces - basking in light in somewhat similar fashion - form a staggering dialogue. The marvelously built up composition represents an iconographic reversal: David seems frail in the face of the enormity of Goliath's head, yet projects - in the horizontality granted to his arms, shoulders, and sword - restrained and decisive strength. The most handsome face of David, carved out by the violent lighting full of shadow, is typical of this artist's clearly defined chiaroscuro. His apparel, a cloth drape, is almost absurdly chiselled out, too strongly. The opposition between black and white bestows a form of presence on David, a suit of armor so to speak. Did Caravaggio paint this work to produce certain effects? Detail of David's

, head, of Goliath

. The belt

. Note the transition from white to ocher in the drape, the technical skill, the speed of the brush. Some of the brushstrokes, taken individually, foretell what would show up in the work of a Velasquez, a Franz Hals. Notice the freedom, the skillfulness of the brushstrokes.

David with the Head of Goliath, Rome, Galleria Borghese.

The dialogue here is between the youth of the living figure and the maturity of the dead one. In this version, the expressions on the faces of David and Goliath are more problematic, tenser. David has triumphed, but is it really a triumph? He conveys pain and anguish in the face of Death, in the face of the mortal blow he just has dealt. Unlike the Vienna version, he is not at all triumphant here; he seems almost at a loss over the responsibility of taking someone's life. Tension-filled melancholy transpires. Chiaroscuro is taken to extremes. Note the visionary manner in which the body is handled, the way it has been deliberately distorted so that the figure seems even frailer.

The expression on David's face shows commiseration, pity. Usually, David does triumph, but here he seems on the verge of crying over what he just did. Notice how the scene as a whole has been simplified. Everything has become more hieroglyphic. David has none of the allure shown in the preceding version. We are presented with meditative sadness, a total lack of setting, the immensity of the night, and a tautened dialogue between the youth of the living figure and the maturity of the dead head. Clearly, this version follows suit and perfects the preceding one.. The

cloth draping

here, in black and white, is among the most beautiful ever achieved by Caravaggio. Goliath

is no longer a simply frightening mask: surprisingly, the expression on his face is more of resignation, as if he were expressing, from the realm of the dead, his acceptance of his own death. The details are so compelling that art historians tend to consider the head as a self-portait

. Did Caravaggio actually wish to immortalize himself behind the features of Goliath, between the latter's great pain and the furious Medusa's terrible shriek of revolt? Be that as it may, one thing is sure: once one has seen this face, been captured by its gaze, it remains unforgettable.

Saint John the Baptist,, Rome, bibliothèque Capitoline.

A St. John the Baptist reminiscent of a Greek shepherd.

Saint John the BaptistBasel, Kunstmuseum, Provenance details not yet established.

Traditionally, John the Baptist is portrayed as an adolescent, accompanied by a lamb, prefiguring the Passion of Christ. This version is a far cry from the High Renaissance portraits in Florentine and Roman art, which present the saint as an ephebe in the Greek manner. The young man shown here is typically 17th-century Italian, with a pallid complexion, handled with no concessions and devoid of the idealism imposed on art by preceding generations. John the Baptist is portrayed in the realist fashion that would become the signature style of Caravaggio. What strikes our attention the most in this work is the way light is distributed. The background is plunged in total darkness. No hint of the setting: a site empty of any familiar objects, landscape, or grotto. It is as if a backdrop had been unfurled behind the figure, a backdrop representing night. In the midst of this dark brown, almost black night, the light aggressively makes certain elements stand out: the youth's shoulder, leg, and profile, together with the body of the lamb. The technical term for this painting with light effects is "chiaroscuro". Caravaggio is the inventor of chiaroscuro used as the main agent of the drama the artist depicts on canvas.

Saint John the Baptist, Rome, Palazzo Corsini

A man in the street. St. John the Baptist is portrayed as older here, a man in the street, whose facial features bespeak a closed and commonplace mind. The round neckline of his attire reveals traces of a tan. This version was found to be shocking at the time.

Saint John the Baptist, Rome, galerie Borghèse.

An ambiguous portrait. The seductive allure of the first version has been completely abandoned here, but this time the face is surprising: it bears the empty expression of someone whose eyes never registered anything. As if he were in a stupor, in the word's etymological sense, but at the same time hollow, ready to resonate. This is an extremely ambiguous portrait.

Saint John the Baptist, Kansas City, W. Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum.

Here, the figure's heroism is more marked, space is taken up in more definite fashion. The play of light and shadow allows the ambiguity of the saint to come through on his face. His face seems peaceful, but the clearcut demarcation between shadow and light lends it violence. It is as if the figure were sculpted out of shadow and light. This version is considered the most similar to Michelangelo in its monumentality. But unlike the latter's epic genius, the monumentalism in this work by Caravaggio takes place in silence. A work of total silence, total serenity, despite the dramatic effects of light and dark.

Era of the Baroque (based on lecture-class notes by Jacques-Edouard Berger). The term first appeared in a dictionary in 1690

- From the Portuguese: barocco

- From the Spanish: berrueco (imperfect pearl)

- In the 18th century: synonym for bizarre

- In the 19th century: granted its current meaning - a strict and austere style- by Jacob Burckhardt:

Temporal context:

- Begins in 1585, when Cardinal Felice Peretti became Sixtus V.

- Ends in 1680, with the death of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Site: Rome. The Holy See. Historical/intellectual context:

- The Sack of Rome by Charles V.

- The Church crisis.

- The Reformation.

- The Counter-Reformation.

- Coalition of orders around the pope.

- Founding of the Jesuit Order «perinde ac cadaver»

- The personality of each pope.

- the church dogma and doctrines were redefined

- abuses of power and special privileges were abolished

- the authority of the Holy See was established

- apropriate instruments were set up - the Roman College, 1556

The Baroque spirit first made itself felt in the 15th entury with such key figures as Girolamo Savanorola, St. Vincent Ferrier, St. Bernardine of Siena. It asserted itself most fully in the 16th century with the creation of various orders: the Capuchin Order (1525), the Theatines, the Barnabites, the Ursulines and, above all, as of 1540, the Jesuits - founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola and approved by Paul III.

All this was accomplished thanks to several faithful greats:

- St. Charles Borromeo in Italy

- St. Thomas of Villeneuve in Spain

- Saint Bartholomew of the Martyrs in Portugal

- St. Francis of Sales in France as well as: St. John of the Cross (Spain), St. Theresa of Avila, St. Francis Xavier (one of the greatest Christian missionaries) and the support of several steadfast popes:

- Pope Pius V (Michaele Ghislieri: 1556-1572 - appointed inquisitor general by Paul IV, reformer of the papal government in Rome, inventor of the index ("Index librorum prohibitorum").

- Pope Gregory XIII (Ugo Buoncompagni: 1572-1585) rectifier of the reformed calendar ("Gregorian calendar"), founder of the Roman College, contemporary of Saint Bartholomew.

- Pope Sixtus V (Felix Peretti, 1585-1590) life enemy of Gregory XIII, sent away from the Curia (body of congregations, tribunals and offices from which pope governs Roman Catholic Church).

- Pope Clement VIII (Ippolito Aldobrandini, 1592-1605)

- Pope Leo XI (Alessandro de' Medici: 1605)

- Pope Paul V (Camillo Borghese: 1605-1621)

- Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini: 1623-1644)

- Pope Innocent X (Giovanni Battista Pamfili: 1644-1655) nuncio (papal legate accredited to civil government) in Naples, Cardinal from 1629,Pope from 1644 -1655, Condemns Jansenism as heretical in 1653.

- Pope Alexander VII (Fabio Chigi: 1655-1667) These then are the people who built the new Rome. To this day, the city's immortal monuments bear the coats of arms of these historical figures.

The Supremacy of Caravaggism

Southern Europe:

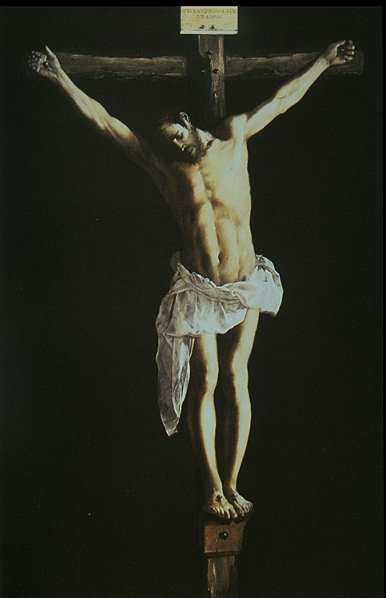

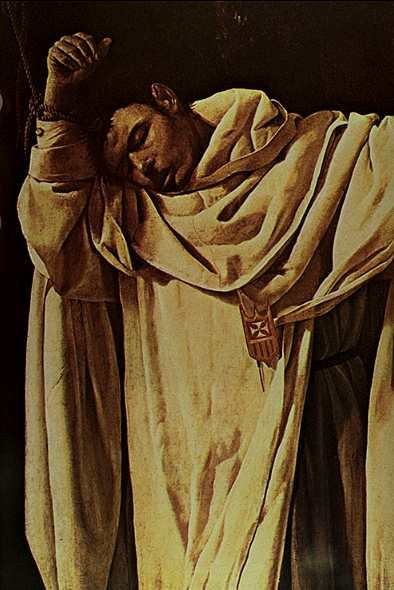

Zurburan 1598 - 1664

Francisco de Zurbarán

Born in Spain, at Fuente de Cantos, Badajoz.A little known, secretive artist who left us neither a self-portrait nor any correspondence.His works were scattered upon the Napoleonic invasion, and his series were dismantled upon the closing of the convents.Only the Jeronymite monastery at Guadalupe (Estremadura) managed to hold on to his works.He worked in Seville, under the wing of Pedro Diaz de Villanevra. His 1627 "Christ" (Chicago, Art Institute) was widely acclaimedby the Sevillians, thus establishing a solid reputation. In 1634, he took up residence in Madrid, where he worked with Velasquez in decorating the new royal palace - Buen Retiro in Madrid - with a series of paintings. He was named official painter to the king.Upon returning to Seville, he encountered great jealousy and animosity from his fellow painters. Commissions slowed down...There is no denying that tastes were changing, and that now Murillo was finding favor with the public.Thereupon, he began working for the Spanish colonies, especially Peru (Lima) through members of his second wife's family.Several works:

- Christ en croix mourant - Chicago, Art Institute

- Exposition du corps -Paris, Louvre Museum

- L'atelier de Nazareth- Cleveland, Museum of Art

- Saint Casilde - Madrid, Prado Museum/a>

- Hercule et le lion de Némée - Madrid, Prado Museum

- Saint François en prière - London, National Gallery

- Le bienheureux Sérapion - Hartford, Conn., Wadsworth Museum

- Apparition de saint Pierre crucifié à saint Pierre Nolasque

- Nature Morte

- Hercule et le lion de Némée - Madrid, Prado Museum

Central Europe: La Tour 1593 - 1652 [1] ,"Trufamond" - 1579 -1650

Bigot, Théophile, known as"Trufamond"

- - 1579: born in Arles- local training as a painter

- 1621-1634: his name appears in the Roman archives, more precisely in the records of the Académie de Saint-Luc

- commissioned to do three paintings for Santa Maria Church in Aquiro

- three attested works in the Giustinani Collection

- passes away in Arles

- presently, his catalogue raisonné lists some forty works

- Vanity, Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Corsini

- Saint Jerome, Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Corsini

- Saint Sebastian

Several works:

Northern Europe: ter Brugghen 1598 - 1629

Hendrick Ter Brugghen

- 1588: Born in Deventer; a pupil of Bloemaert.

- 1604: Journey to Italy, where he would remain ten years in Rome, and return via Milan; first of the northern painters to discover Caravaggio.

- 1616: Joins the St. Luke Guild in Utrecht.

- 1629: Passes away in Utrecht.

In this painting

The Concert, 1626-1627, London. National Gallery.

[1] Les clés du regard

The catalogue of works "Tout l'oeuvre peint de Caravage" in the " Classiques de l'Art" series published by Flammarion inventories 73 works. In "Caravage" published by Gallimard/Electra, Mina Gregori presents 87 of the painter's works. The present program offers 37 of Caravaggio's works (provenance updates according to Mina Gregori's "Caravage", Gallimard/Electra, Paris, 1995)

- Secular works: Caravaggio, painter of genre (everyday life) scenes. Rome

Medusa Head Shield

- Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi (ca. 1597-9)

Boy with Fruit Basket

- Rome, Galleria Borghese (1593-94)

Boy Bitten by a Lizard

- London, National Gallery 1595-96 (cf. also 1596-97, Florence, Fondazione Roberto Longhi)

Bacchus

- Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi (ca. 1596-97)

Sick Little Bachus

- Rome, Galleria Borghese (ca. 1593)

The Fortune-teller

- Paris, Musée du Louvre (1596-97) (cf. also 1593-94, Pinacoteca Capitolina)

The Cardsharps

- Fort Worth (Texas), Kimbell Art Museum (ca. 1594)

Narcissus

- Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Corsini (ca. 1598-99)

Basket of Fruit

- Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana (ca. 1597-98)

- First religious paintings - Great figures :

Rest During the Flight into Egypt ">

">

- Rome, Galleria Doria-Pamphili (ca.1595-1596)

Judith Beheading Holofernes

- Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini(1597-98)

- Recurrent themes:

- St. John the Baptist :

1602, Rome, Musei Capitolini

1603-04, Kansas City, W. Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art

ca. 1603-04, Rome

, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica Palazzo Corsini

1609-1610, Rome, Galleria Borghese

Basel, Kunstmuseum

- David avec la tête de Goliath:

(cf. also, Madrid, Prado, 1597-98)

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum (1607)

Rome, Galleria Borghese (1610)

- (Last) Supper at Emmaus:

London, National Gallery (1601)

Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera (1606)

- Solitary figures period::

Penitent Magdalene

- Rome, galerie Doria-Pamphili (1594-95)

Saint Catherine of Alexandria

- Madrid, collection Thyssen (1597)

Saint Jerome

- Rome, galerie Borghèse (1606) (cf. also 1608, La Vallette(Malta) Cathedral St. John)

- The San Luigi dei Francesi cycle: the life of St. Matthew

Calling of Saint Matthew

(1599-1600)

- Martyrdom of Saint Matthew

(1599-1600)

Saint Matthew and the Ange

(1602)

- Mature period:

- Rome:

Madonna of Loreto, or Madonna of the Pilgrims

- Eglise Sant' Agostino

Crucifixion of Saint Peter

- Eglise Santa Maria del Popolo

Conversion of Saint Paul

- Eglise Santa Maria del Popolo

Entombment

- Pinacothèque Vaticane (1602-04)

Death of the Virgin

- Paris Musée du Louvre (1601-1605)

- Naples:

Madonna of the Rosary

- Vienne, Kunsthistorisches Museum (1606-1607)

Seven Works of Merc

- Naples, Pio Monte della Misericordia Church(1607)

- La Vallette (Malta):

Décollation de saint Jean-Baptiste

- La Valette, Malte, Cathédrale Saint-Jean (1608)

- Sicily:

Beheading of St. John the Baptist

- Messine, Musée Régional (1608-09)

Adoration of the Shepherds

- Messine, Musée Régional (1609)