René Berger

Chevilly, mai 1997

In what terms then can we designate a site that, as dusk falls, stretches far beyond our field of vision, a site that dumbfounds the prestige "categorization" typifying our narrow cultural outlook? For as gigantic as it is, Angkor Wat has never offered access to any mortal Sun King: here divinity belongs to the gods, whose presence is intimated in the mirror images moat and sky throw back at each other.

Our cultural grids blur in the face of a site so inspiring as to expand beyond any demarcation line between real and unreal. Gradually we intuit, in ever more pregnant fashion, that here perhaps - and for the first time - discovery precedes acquired knowledge. Generally, the sum of our knowledge streams downwards from our education and milieu, as we learn to integrate it with an eye to developing a conceptual platform to serve as a "frame of reference" for our value judgements. But to set foot in Angkor is an upstream experience bringing the exalting feeling that here exists a presence that is nigh to contemporary.

The Khmer civilization is doubly paradoxical: born and developed within but a few centuries, it blossomed into a unique religious and artistic creation, only to be relegated to almost complete oblivion for a long period of time. Yet archaeologists have charted over a thousand monuments that are, today, scattered across Cambodia, not to mention those that have survived in Thailand and the rest of Southeast Asia. Now at last we are again allowed to marvel at one of civilization's wealthiest troves, not merely founded in full by art but even so-to-speak "impregnated" by it, considering how close it all came to being reduced to naught due to the vagaries of politics. Thus, it is much as if we were being offered a chance to witness, even participate in, a new birth. Such terms barely do justice to our awe upon seeing temple after temple emerge from the forest, their contours modelled by light and shadow and, from time to time, accented by the saffron swish of a passing monk's robe. One does not "pay visit" to Khmer temples. Rather, in their company, one aspires to the Hindu and Buddhist dimensions once boasted by famous as well as lesser known priests of these religions. Indeed, these would all have disappeared from the memory of man were it not for the far-reaching glow radiated by the Bayon Temple: its multitude of faces sweeping the horizon; its bas reliefs teeming with life at the core of their gleaming silence, and hosting the ineffably smiling apsaras who, as they flit by like a swarm of butterflies, testify to the visibility of the invisible. Countless figures anchored in stone, yet that project forward in an invitation to join the cosmic dance they at once animate and mediate. Now at last then, we can contemplate the earthly and divine space once belonging to the Khmer, outside and inside - as it were - merging under our gaze. Complementaries flower in stone scrolls that give off melodies, resonances, tones. The unheard of makes itself heard. Forms steal past our need to identify them, dragging us along, above and beyond our gaze, into the movement that is the site's basic unity.

However exalted - and exalting - they be, these sanctuaries cannot escape the earth that houses them, the winds that blow across them, all of which serve to feed the giant roots that entwine them to the point of bursting their walls and sculptures. Such terrestrial power takes us aback. Yet, reversing the phenomenon's metaphorical implications, might we not just as legitimately consider these effects of nature as acts of love, as if the roots could be said to hoist the temples up towards the tree foliage? As if, rather than the cataclysm that meets the eye, there could be said to exist a secret alliance between stones transformed into trees, and vegetation transformed into architecture?

In such fashion, the fury of the battles of yore is brought into harmony with the serenity of the gods, turbulency is calmed into order, and immanence and transcendence form a third unity forever veiled yet palpable. The prodigious grip of the elements holds sway, in the absence of any figures or witnesses, lest it be the maidens here and there holding out their flute to us: their smile promises the rebirth of creation, thanks to a single note of music springing forth from the lips of these, the mothers of tomorrow.

René Berger

Chevilly, 11 May 1997: Mother's Day

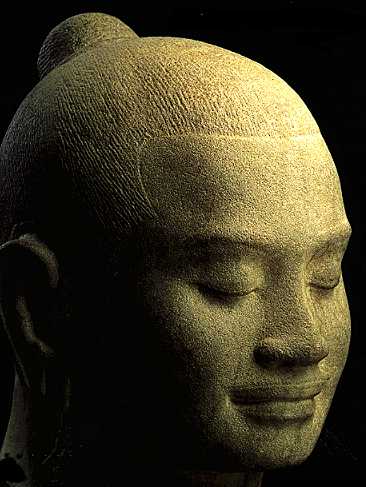

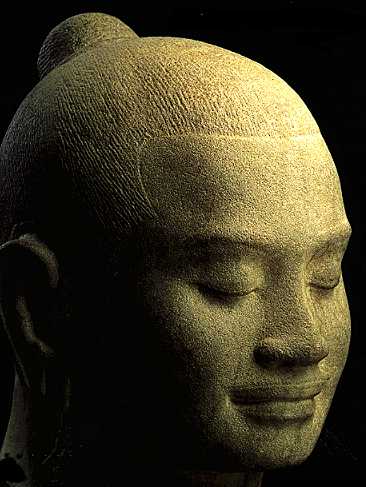

The idealized faces the sculptors of ancient Cambodia so skilfully managed to draw forth from stone represent strikingly realistic portraits that capture the majesty and impassivity of gods, as well as the compassion of divinities imbued with a gentle inner smile.

In their bas-reliefs, these artists devoted their talent not only to depicting the deities, but to realistically reproducing the secular world as well: the temple gallery walls are lined with military processions, raging battles, or simple everyday scenes carved with an amazing sense of movement and composition.

Starting with the first Preangkorean masterpieces - which can be traced from as early as the 6th century AD - and continuing during the Angkorean period from the 9th to the 15th centuries as well as during the Postangkorean period, Khmer stone sculptors looked to religion for inspiration. It is in glorification of their gods or deified kings that the artists, forever condemned to anonymity, created their temples, statues, and bas-reliefs. Indeed, their works represent genuine professions of faith and honor with respect to India's two main religions, Hinduism and Buddhism, introduced to Cambodia during the first centuries of the Christian era.

In the sanctuaries, the statues were sculpted in a contemplative sitting pose or standing upright, and were represented holding out in their hands the attributes by which they could be identified. They were expected to be inhabited by a deity (mainly Shiva and Vishnu, but Buddha too), from whose protection and blessing believers hoped to benefit.

It is the Brahmanist belief that Shiva, god of both regeneration and destruction, incarnates the cosmic order of things. The images of this god - dancing, with one head and two arms, with five heads

, sous la forme du Linga

, sous la forme du LingaIdol representing the phallus of Shiva, as a symbol of his creative power.

, etc... - translate his complexity. Shivaism remained the most steadfast of Cambodia's religions during the Preangkorean and Angkorean periods.

Vishnu, the god of preservation, also inspired a major religious movement. Iconographically, he is most often represented as a four-armed god, with at first a cylindrical mitre as headdress and, later, a sort of stone diadem. The discus, conch, mace, and sphere (symbolizing the world) are this god's emblematic attributes.

In Khmer tradition, Buddha is often depicted in a meditative pose, seated on a base in the form of either a spread out lotus or a nâga

Water spirit in the form of a serpent, generally many-headed.

serpent whose seven heads fan out above him to afford protection.

Olivier Saltet

Direct carving was the preferred method: after first roughly blocking out the form, the artist continued to refine it until form and volume met the standards set in various treatises on works of art, termed "çilpaçatras". The final artistic products could vary in size by from ten centimeters or so up to two meters.

L'équilibre dans l'espace

From the beginning, Khmer artists sought to liberate their works from the influence of the Indian models to be found carved in high relief along the temple walls, or propped against a stela.

The famous

From the beginning, Khmer artists sought to liberate their works from the influence of the Indian models to be found carved in high relief along the temple walls, or propped against a stela.

The famousLe célèbre Krishna du Mount Govardhana Krishna of the Wat Koh (end 6th century) was still executed in high relief. At this time already, however, the statues "in the round" of deities with two arms had but a strut under each hand to keep their balance. The four-armed Vishnus were encircled by support arches as props to their upper arms. In such masterpieces of free-standing sculpture as the goddesses Durga in the "Sambor Prei Kuk" style (first half of the 7th century) and Devi of the Koh Krein (7th century), the artist achieved flowing and sensuous contours that release the figures into space. This holds true as well of Harihara (end 7th century), a divinity who features aspects of both Vishnu and Civa.. This statue elegantly combines realism - the expressivity of the face, the shaping of the legs, the rendering of the material of the sampot

Short garment worn draped around the hips and knotted together at the front.

with the stylization featured in the figure's bust and hairdo.

As to the Buddhas, dressed in monk's robes, the figures were not propped against anything but their feet were sculpted in high relief.

By the 9th century, struts and support arches had disappeared. Statuary in the "Preah Ko" style (end 9th century)was created to stand freely in space. On the other hand, their bodies thickened: with swelling chests and widening hips, they were set on heavy legs. This tendency reflects the artistic striving to convey the ideal of power, resulting in a hieratic treatment verging on rigidity, as recognizable in the "Bahkeng style" (end 9th and beginning 10th centuries).

Hieratically and freely treated forms

During the first half of the 12th century, the powerful King Suryavarnam II commissioned the monumental temple of Angkor Wat, in honor of Vishnu. Les artistes de la période angkorienne portent alors à la perfection les normes héritées d'une tradition vieille de plusieurs siècles.

During the first half of the 12th century, the powerful King Suryavarnam II commissioned the monumental temple of Angkor Wat, in honor of Vishnu. Les artistes de la période angkorienne portent alors à la perfection les normes héritées d'une tradition vieille de plusieurs siècles.

The Angkor period artists availed themselves of the occasion by fulfilling to perfection artistic standards inherited over the centuries. The imposing architectural majesty of the temples inspired sculptors to handle the idols inhabiting them hieratically, thus endowing them with superhuman dimensions. The final effect was of a certain rigidity, as underscored by their very physique - square shoulders, thrust out chests, unmodelled legs - and by such vestiary details as their elaborate finery and the rectilinear pleats of their attire.

Feminine divinity.

and "apsaras"

Celestial dancer.

enliven the temple walls: at Angkor Wat, over 1700 have been inventoried, all of which delight viewers with their exquisite gracefulness, enhanced by the great variety of their attire and finery, and their cheerful demeanor. These feminine figures with their smiling faces are to be found under an arcature or amid a leafy decor; they appear individually or in groups, either in a state of silence or engaged in conversation. Here, one of them raises her finely defined head crowned by a three-pointed tiara, while her hand fondles a trailing strip of her dress. There, another raises a mirror to her face. And there, still another, having slipped a flower into her hair, puts her arms around her companion's shoulders.

The smile of Bayon

One of the greatest kings of Cambodia of yore, Jayavarman VII - an authoritarian and conquering monarch who was nonetheless an unshakeable and compassionate Buddhist as well - played a major role with respect to sculptural developments during the second half of the 12th century. A high point was achieved with the temple mountain of Bayon style, most renowned for its "smile of the Bayon" reflecting the Buddhist ideal of detachment. The "four-faced towers" to be seen on the temples of the era, and on the summit of the five gates of the new capital Angkor Thom, can be considered as both architecture and sculpture. These giant heads of Bodhisattva Bodhisattva

One of the greatest kings of Cambodia of yore, Jayavarman VII - an authoritarian and conquering monarch who was nonetheless an unshakeable and compassionate Buddhist as well - played a major role with respect to sculptural developments during the second half of the 12th century. A high point was achieved with the temple mountain of Bayon style, most renowned for its "smile of the Bayon" reflecting the Buddhist ideal of detachment. The "four-faced towers" to be seen on the temples of the era, and on the summit of the five gates of the new capital Angkor Thom, can be considered as both architecture and sculpture. These giant heads of Bodhisattva Bodhisattva In the Buddhist religion, "destined for enlightenment"..

Lokeçvara

In the Buddhist religion, the bodhisattva of compassion, lord of the world.

are over two meters high. They gaze out at the four points of the compass with faces that are not only serious and contemplative but, at the same time, endowed with an enigmatically bewitching smile.

With his eyes lowered and lost in inwardly-turned contemplation, the sculpted head of Jayavarman VII of Preah Khan (known as Kompong Svay) represents - more than any other work - the acme of universal sculpture. His countenance, gently brought alive by the slight smile on his lips, conveys for eternity the ideal of bliss and beauty towards which the sculptors aspired.

With his eyes lowered and lost in inwardly-turned contemplation, the sculpted head of Jayavarman VII of Preah Khan (known as Kompong Svay) represents - more than any other work - the acme of universal sculpture. His countenance, gently brought alive by the slight smile on his lips, conveys for eternity the ideal of bliss and beauty towards which the sculptors aspired.The onset of decline

When Cambodia converted to the Theravâda

When Cambodia converted to the Theravâda

Buddhism: Teaching of the Elders". Earliest form of Buddhism, also named "Lesser Vehicle".

school of Buddhism during the Postangkorean era, the iconography of sculpture "in the round" underwent radical change: the Brahmanist images disappearing from the scene were replaced almost entirely by images glorifying Buddha. During the 13th and 14th centuries, statuary continued to follow in the Bayon style tradition.

From the end of the 15th century, the Khmers gave up stone constructions. In line with this trend, artists cast their works in bronze and, above all, sculpted in wood their images "in the round" and reliefs on panels. Of the latter two, given their perishable nature, many have returned to dust in the meantime.

All its splendor during Angkorean times notwithstanding, the art of stone carving itself was to fall into oblivion over the next few centuries.

The Shivaist temple of Banteay Srei (968) is considered a jewel in the crown of Khmer art. A luxuriant wealth of decoration - stylized plant themes, friezes, arcatures, representations of humans and animals in relief or "in the round" - was carved out of a delicately nuanced pink sandstone

The Shivaist temple of Banteay Srei (968) is considered a jewel in the crown of Khmer art. A luxuriant wealth of decoration - stylized plant themes, friezes, arcatures, representations of humans and animals in relief or "in the round" - was carved out of a delicately nuanced pink sandstone . Never before - and never as dextrously - had artists brought to life the legendary scenes from the life of Shiva. The sumptuous bas-reliefs of the eastern pediment of the south "library", for instance, narrate the attack on Shiva's sacred mountain, the Kailas, by the demon Ravana. Luckily, this extraordinarily detailed masterpiece is in a particularly excellent state of preservation.

. Never before - and never as dextrously - had artists brought to life the legendary scenes from the life of Shiva. The sumptuous bas-reliefs of the eastern pediment of the south "library", for instance, narrate the attack on Shiva's sacred mountain, the Kailas, by the demon Ravana. Luckily, this extraordinarily detailed masterpiece is in a particularly excellent state of preservation.

The bas reliefs to be found at Angkor Wat also enjoy great renown among the treasures of Khmer art. The enormous compositions spread out along the outer wall galleries, some of which are up to 90 meters long, include scenes from the

last battles

The bas reliefs to be found at Angkor Wat also enjoy great renown among the treasures of Khmer art. The enormous compositions spread out along the outer wall galleries, some of which are up to 90 meters long, include scenes from the

last battles of the Ramayana

of the RamayanaOne of India's two great epics (along with the Mahabharata), relating the adventures of Rama. Allying with the King of the monkeys, Rama struggles to recover his throne and his wife Sita, abducted by the demon Ravana.

and Mahabharata

One of India's two great epics (along with the Ramayana), narrating the rivalry between the five sons of Pandu, the Pandavas, and their cousins, the 100 Kuaravas. In their struggle, the Pandavas were asisted by Krishna, an avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu.

epics, the great myth of creation known as the "churning of the Sea of Milk" to obtain the beverage of immortality ("amrita"), and King Suryavarman II setting out to war on a four-tusked elephant. With consummate mastery, the sculptors incised the outlines of the figures, bringing out their volumes and defining the intricate details of their faces, bodies, finery, battle chariots, and warriors-in-arms.

A universe of the gods, a world of men

At the temple mountain of Bayon, the gallery bas-reliefs not only narrate legends in the Brahmanist tradition, but also depict historic scenes: impatient to repel the Chams, the armies of Jayavarman VII

At the temple mountain of Bayon, the gallery bas-reliefs not only narrate legends in the Brahmanist tradition, but also depict historic scenes: impatient to repel the Chams, the armies of Jayavarman VII march off to battle. War vessels are engaged in naval combat. Further along, picturesque realism and even an occasional dab of humor characterize stone representations of everyday scenes that provide valuable insights into the life of the Khmers of yore. Peasants travelling

march off to battle. War vessels are engaged in naval combat. Further along, picturesque realism and even an occasional dab of humor characterize stone representations of everyday scenes that provide valuable insights into the life of the Khmers of yore. Peasants travelling  by cart are shown with their entire families. Also depicted are women holding their last-born on their hips, betters at a cockfight, a little girl stealing from a sleeping market stall keeper, etc....

by cart are shown with their entire families. Also depicted are women holding their last-born on their hips, betters at a cockfight, a little girl stealing from a sleeping market stall keeper, etc....

The same great era of Jayavarman VII saw the construction of the Terrace of Elephants

The same great era of Jayavarman VII saw the construction of the Terrace of Elephants bordering the remains of the ancient Palais Royal along an almost 300-meter stretch. The terrace walls and those lining the stairway perrons boast an impressive

bordering the remains of the ancient Palais Royal along an almost 300-meter stretch. The terrace walls and those lining the stairway perrons boast an impressive series of "garudas"

series of "garudas"Divine bird (half-eagle, half-man), enemy of the nagas and mount of the god Vishnu: Oiseau divin à corps humain, ennemi des serpents nâga et monture de Vishnu.

and lions as atlantes. Other bas-reliefs picture chariot races. Almost life-size elephants ridden by their "mahouts" and presented in profile

belong to hunting scenes executed in high relief.

belong to hunting scenes executed in high relief.- 1- Ak YumBeginning of 7th century, Hindu The first temple mountain and one of the earliest known sites in the area, preceding the first Angkor and thought to be central to the first ancient capital city. A small three tiered pyramid in brick with primary elements in sandstone, still mostly buried under the 11th century dike of the western baray. Inscriptions give the dates 609 AD, 704 AD and 1001 AD and reveal that the temple was dedicated to the god Gambhiresvara.

- 2- Prah Kô (Roluos Group)

879 AD, Indravarman I Hindu (Shiva) The funerary temple of Jayavarman II and his predecessors, enclosed within a moat of 400 by 500 metres. The foundation stele (an inscribed monolith) tells of the genealogy of Indravarman I, with a reference to the cult of the god king, and the foundation date of three statues of Shiva and Devi in 879 AD. The other face of the inscription dates from 893 AD under the reign of Yasovarman and describes certain dedications. The temple still has a large area of moulded stucco (a lime-based plaster mixture) remaining intact, though only just.- 3- Bakong (Roluos Group)

881 AD, Indravarman I Hindu (Shiva) A temple mountain enclosed by a laterite wall and two moats, the outer of which measures about 900 by 700 metres. The third such temple after Ak Yum and Rong Cheng (at Phnom Kulen to the north east) and the first to make extensive use of sandstone. The stele tells of the foundation of the linga (a stone phallus, representative of Shiva) in 881 AD. The brick towers have finely detailed sandstone elements and some remnants of stucco moulding. The central sanctuary in the Angkor Wat style, which was probably built two centuries after the main temple, was resurrected from a pile of rubble between 1936 and 1943.- 4- Lolei (Roluos Group)

893 AD, Yasovarman I Hindu (Shiva) Four brick towers (though perhaps originally six) set on a two tiered base in the middle of the Lolei Baray, (Indratataka), a large ancient reservoir of 3.8 by 0.8 kilometres. Excavation of the baray began, so the inscription tells us, five days after the consecration of Indravarman I at Bakong, in order to irrigate the capital city centred there. The temple, built subsequently, is dedicated to his memory.- 5- Phnom Bakheng

End of 9th century, Yasovarman I Hindu (Shiva) Located at the centre of the first capital of Angkor which formed a square of about 4km surrounded by a moat of which the south west quarter is still visible. The remains of an inner enclosure of 650 by 436 metres surrounds the base of the hill. A 'natural mound' five tiered pyramid temple, the bulk of which is hewn from the bed-rock and faced with sandstone. The location gives good views over the surrounding landscape, particularly at sunset.- 6- Phnom Krom

End of 9th century, Yasovarman I Hindu Perhaps the second of three temples built by Yasovarman I on the hills dominating the Angkor plain - the others on Phnom Bakheng and Phnom Bok. Badly deteriorated. Enclosed in a square laterite wall, three sandstone sanctuaries aligned north-south are dedicated to the Brahmanic trinity - Shiva between Vishnu (north) and Brahma (south). Good views over the Tonle Sap lake.- 7- Prasat Thma Bay Kaek

10th century. A ruined single square brick tower preceded to the east by a laterite terrace, situated between Baksei Chamkrong and the moat of Angkor Thom, 125 metres west of the main road. When cleared in 1945, five gold leaves arranged in a quincunx where found under the base step.- 8- Prasat Bei

10th century. Hindu (Shiva) Three small brick towers aligned north south on a common laterite base, 175 metres west from the above.- 9- Prasat Kravan

921 AD, Hashavarman I Hindu Five brick towers, aligned north - south on a common brick base, within a single enclosure and moat. The extensive brickwork restoration uses cement mortar where originally there would only have been a thin vegetal adhesive or clay slurry. The inscribed door frames mention the setting of a statue of Vishnu in 921. There are bas-reliefs representing Vishnu, and other representations of Lakshmi in the internal brickwork of the central tower, and of the northern most tower. Best in the morning sun.- 10- Baksei Chamkrong

947 AD, Hashavarman I, Rajendravarman II Hindu (Shiva) A temple mountain set back in the trees at the base of Phnom Bakheng, in materials typical of the 10th century. A brick tower opening to the east and originally decorated with stucco moulding surmounts four diminishing tiers in laterite, the upper most of which is moulded, enclosed within a brick wall which has virtually disappeared. Four axial stairs each ascend in a single flight.- 11- Mebon Oriental

952 AD, Rajendravarman II Hindu (Shiva) At the centre of the Eastern Baray and so originally only accessible by boat. All the characteristics of a temple mountain in brick and laterite but with a three metre high platform carrying five towers arranged in a quincunx rather than a central tiered pyramid. A large foundation stele describes the dedication to the king's parents. The east west axis of the temple aligns with the principal entry to the royal palace in Angkor Thom. Sandstone lintels are superbly detailed. Monolithic elephants stand at the four corners of each enclosure, those to the south west being particularly well preserved. Good in the late afternoon.- 12- Bat Chum

953 AD, Rajendravarman II Buddhist The first known Buddhist temple. Three brick sanctuaries with the main architectural elements in sandstone on a common moulded laterite base. Inscriptions give details of dedications to three Buddhist divinities and reveal the architect of the Eastern Mebon as its patron and builder.- 13- Pre Rup

961 AD, Rajendravarman II Hindu(Shiva) On the same north south axis as the Eastern Mebon which it follows by only 9 years. Similar in style and composition, though much grander. Again built almost entirely in laterite and brick but with the main architectural elements in sandstone. The lintels are finely detailed - some remain unfinished. The upper brick towers would have been adorned with stucco moulding. Probably central to the second capital which developed following its return from Koh Ker to where it moved between 921 and 944. It is thought that the royal palace was situated close by.- 14- Banteay Srei

967 AD, Rajendravarman II, Jayavarman V Hindu (Shiva) A temple in the forest 25 kilometres to the north east of Angkor Thom. A jewel to which the nature of the material used - a finely textured rose coloured sandstone - is perfectly suited. Monumental size and architectural theme give way to a miniature scale and a dense and exquisite detail in near perfect preservation. Dismantled and reconstructed between 1931 and 1936.- 15- Ta Keo

11th century, Jayavarman V, Suryavarman I Hindu (Shiva) An imposing five tier temple mountain built predominantly in sandstone and surrounded by a moat. Perhaps central to the next capital. Best approached from the original eastern entrance where the massive form of the temple is presented framed in trees at the end of the entrance causeway. The clear constructional intention is all the more visible since the decoration was never completed. Inscriptions on door frames of the eastern gopuras relate to dedications made in 1007.- 16- The Khleang

Beginning of 11th century, Jayavarman V, Suryavarman I The two Khleangs are similar buildings of uncertain function. The one to the north was built first - two inscriptions date from 1002 to 1049. Inscriptions within the south Khleang are similar to the oaths of functionaries engraved on one of the door jambs of the east gopura of the royal palace enclosure.- 17- Phimeanakas

11th century, Suryavarman I, Udayadityavarman II Hindu The Royal Palace of the next capital was enclosed within a five metre high laterite wall that is doubled by a second of later construction. At the centre of this enclosure is Phimeanakas, a three tiered rectangular pyramid built in laterite, which was perhaps a private royal chapel. The composition diminishes with height and so gives a false perspective - a characteristic device of the temple mountains.- 18- Baphuon

Middle of 11th century, Udayadityavarman II Hindu (Shiva) A three tiered temple mountain to the south of the Royal Palace enclosure. It is the "impressive copper tower even higher than the tower of gold" (the Bayon) described by Tcheou Ta-Kouan, a Chinese diplomat visiting at the end of the 13th century. Probably the central temple of the fourth kingdom of Angkor.- 19- Prah Pithu

Beginning of 12th century, Hindu / Buddhist A collection of five small temples (one of which is Buddhist) and a terrace (a stone plinth originally supporting some form of lightweight structure) situated at the far north-east of the royal square. Unfortunately badly ruined, but the high platforms on which they are built and that which remains of their lower levels - the upper levels having disappeared - reveals a high quality of decoration and classifies them with the best period of classic art - that of Angkor Wat (first half of the 12th century).- 20- Angkor Wat

Beginning of 12th century, Suryavarman II Hindu (Vishnu) A pyramid temple in three tiers built on an artificial mound with four enclosures and opening unusually to the west, suggesting this was the funerary temple of Suryavarman II. The external wall forms a rectangle of 1025 by 800 metres which is enclosed by a moat 190 metres wide. Overall a square kilometre of bas-relief sculpture to view. Best in the late afternoon.- 21- Thommanon

Beginning of 12th century, Suryavarman II Hindu Extensively restored in contrast to Chau Say Thevoda just to its south. A single ruined laterite wall, 45 by 60 metres, surrounded by a moat and divided by two gopuras encloses both a finely detailed central sanctuary set on a 2.5 metre high moulded base and a single library.- 22- Chau Say Tevoda

Beginning of 12th century, Suryavarman II Hindu Similar in style to Thommanon, but in an advanced state of ruin. A raised causeway on three rows of piers links the temple via a cruciform terrace to the river. The foundation date is uncertain but the quality of decoration places it, with Thomanon, between the extreme limits of the Baphuon and Angkor Wat style, from the end of the 11th to the middle of the 12th centuries.- 23- Banteay Samre

Beginning of 12th century, Suryavarman II Hindu (Vishnu) Located 14 kilometres to the north east of Siem Reap. A finely proportioned temple from the classic period. Undated but perhaps a little later than Angkor Wat, the interior is similar in layout to Chau Say Tevoda with which it is perhaps contemporaneous. Dismantled and reconstructed between 1936 and 1944. The Samres were a people of mixed origin who were said to have lived at the base of the Kulen hills.- 24- Ta Prohm

1186 AD, Jayavarman VII . Buddhist A large Buddhist monastery of five enclosures. Unrestored and deliberately left to the elements with dramatic results - though many of the large trees which give the temple its character are dying. Dedicated to the mother of Jayavarman VII, the inscription tells us that within the walls were 12,640 inhabitants of which 13 were high priests, 2,740 officials, 2,232 assistants, and 615 dancers. Best in the morning.- 25- Bantéay Kdei

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Buddhist A temple of four enclosures, the outer measuring 700 by 500 metres, showing signs of at least two stages of construction in differing styles. Typical of Jayavarman VII, but in an advanced state of decay.- 26- Srah Srang

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII A large basin (the royal bath), 700 metres by 300, set on the axis of Banteay Kdei and bordered by stone steps. Originally excavated during the mid 10th century, to its west is an elegant terrace, and nearly at its centre a small island on which there are some sandstone remains.- 27- Prah Khan

1191 AD, Jayavarman VII Buddhist A royal city forming a rectangle of 700 by 800 metres surrounded by a moat and similar to Ta Prohm, but with only four enclosures. Opens to the east to a baray (at the centre of which is Neak Pean) via a terrace originally used as a boat landing. The large stele, discovered in 1939, tells us that the temple was dedicated to the king's father. It also refers to the small stone building within the fourth enclosure to the east (like the one at Ta Prohm) as 'a house of fire' - perhaps for visiting pilgrims. The many small holes in the stone of the central sanctuary could perhaps have been used to fix a bronze panelling. Larger holes seen elsewhere were generally used for lifting. Good at any time.- 28- Neak Pean

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Buddhist 'The entwined naga'. Built as an island, 350 metres square, in the middle of the Preah Khan Baray. A square central basin has at its centre a circular base for the sanctuary ringed with two entwined nagas (serpents). Four gargoyles in small sanctuaries discharge into smaller square basins to each side in a form which replicates the sacred lake of Anavatapta in the Himalaya, venerated for its powers of healing.- 29- Ta Som

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Buddhist To the east of the Prah Khan baray and almost on its central axis. Typical of the later period of the Bayon style with three enclosures similar to those at Ta Prohm and Banteay Kdei. The various buildings which still stand are in an advanced state of ruin.- 30- Ta Nei

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Buddhist In an isolated position to the north of Ta Keo. Relatively well preserved though deteriorating, the main temple has four cruciform entrance gopuras in sandstone connected by galleries with walls in laterite and vaulted sandstone ceilings. Corner pavilions, a central sanctuary and a library in the south eastern corner are also in laterite and sandstone. Inscriptions on door jambs give details of divinites to whom the temple was dedicated.- 31- Bayon

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Buddhist At the centre of the last city of Angkor and perhaps a microcosm of the kingdom with representations of all the major divinities - Buddhist to the south and east, and Hindu to the north and west. 200 large faces adorn the 54 towers signifying the omnipresence of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, the kingdom's principal divinity. There are indications that the temple was built in stages with much architectural indecision. Best early in the morning or, if you get the chance, by the full moon. Don't miss the bas-reliefs.- 32- Prasat Suor Prat

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Hindu (Vishnu) The towers of the rope dancers. Twelve sanctuaries in laterite and sandstone to the west of the royal terrace which perhaps had some ceremonial function.- 33- Banteay Prei

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Buddhist A small temple in the Bayon style to the north of Prah Khan. Two enclosures, the outer of which is surrounded by a moat.- 34- Krol Kô

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Buddhist A small temple of two enclosures. The central tower in the Bayon style is preceded by a library, built of laterite and sandstone, to the south of the axis.- 35- Ta Prohm Kel

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Buddhist A lone sandstone tower within a single ruined laterite enclosure. The stele discovered at Ta Prohm in 1928 gives details of 102 hospitals established by Jayavarman VII. This building is probably the chapel of one of these. One stands outside each of the cardinal gates to Angkor Thom.- 36- The Elephant Terrace

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII The foundation platform of the royal audience hall, described by Chou Ta-Kuan in 1296 -"In the counsel hall, the window frames are of gold: to the left and right are square pillars bearing forty or fifty mirrors, below them are elephants...". "Here, on the central perron amidst the ringing of conches, when the golden curtain was drawn aside by two servants, the king of Angkor, seated on a lion skin, appeared before his prostrated subjects." - G.P. Groslier.- 37- Terrace of the Leper King

End of 12th century, Jayavarman VII Named after the statue found there which is in fact of Yama, the god and judge of the dead. From epigraphic evidence, Georges Coedes suggests therefore that it may have been the location of Hemagri - the mount meru - where the "inspector of faults and qualities" perhaps once held court beneath a wooden edifice. Published in 1944 in Saigon, republished in 1948 and again in Paris in 1963, "The Monuments of the Angkor Group" by Maurice Glaize remains the most comprehensive of the guidebooks and the most easily accessible to a wide public, dedicated to one of the most fabled architectural ensembles in the world.

The Khmer, from origins to contemporary timesIf one is to believe the legend, the ancient dynasties of the Khmer empire were derived from the union of a Hindu prince, Preah Thong - who had been banished from Delhi by his father - with a "female serpent-woman", the daughter of the Nagaraja who was sovereign of the land. She appeared to him in radiant in beauty, frolicking on a sand bank where he had come to make camp for the night. He took her as his wife, and the Nagaraja, draining the land by drinking the water that covered it, gave him the new country, called it Kambuja and built him a capital.A variation, revealed on an inscription at Mison in Champa (mid Vietnam) and reproduced in various descriptions of Cambodia, substitutes for the prince the Brahman Kaundinya, who "married the nagi Soma to accomplish the rites" and, throwing the magic lance with which he was armed, founded at the point of its landing the royal city where Somavamsa, the race of the moon, would rule.

Another popular tradition, though less widespread, gives as the origin the coupling of the maharashi Kambu and the apsara Mera, whose union is symbolic of that between the two great races, solar (Suryavamsa) and lunar (Somavamsa). This survives particularly in the word Kambuja - son of Kambu - from where derives the name "Cambodian" by which we now call the present descendants of the ancient Khmer.

Whichever version one takes, the mythical implication is undeniable and the truth remains - that the Khmer people are born of a joining of two distinct elements; Indian and native. They are not, as some would believe, simply a people of purely Indian or Hindu origin who had come, following migration, to settle in a region devoid of any inhabitants, or where the indigenous race had been eliminated by mass deportation.

Established since prehistoric times in the lower Mekong valley of the southern Indo-Chinese peninsula, that included not only present day Cambodia but also Cochinchina and parts of Siam and Laos, they were in fact a mixture - from an ethnological rather than a linguistic point of view - of people from lower Burma and various barbarous people from the annamitic chain, themselves in turn quite probably deriving from Negroid and Indonesian roots. The Indian contribution apparently resulted from a natural expansion towards the east for commercial, civil and religious reasons rather than for any brutal political motivation.

Moreover, with the fall of the Khmer empire - that so captures the imagination in the extent and apparently abrupt timing of its destruction - came perhaps a total decline and abandonment of the capital, but, mysteriously, not the entire extinction of the race. With a little help from France and a clear understanding of the glory of their past, these people soon regained an awareness of their value and began to rise again, having never ceased to exist. Having retained their fundamental characteristics - their traditions, their religion and their language - their artistic talents need only the opportunity to revive.

Some physical catastrophe, earthquake, flood, or a drying up of the country's economy has been suggested, and though it is difficult to accept that an earthquake could leave so many stone structures standing, there are however indications, such as the filling of the enormous basins and low areas of Angkor Thom and its suburbs, that render the suggestion of an overflow of the Great Lake or the rupture of some dike plausible - and it is common that such disasters usually result in epidemic and devastation. Likewise, the collapse of a perfected hydraulic system that gave life and fertility to the region could have quickly transformed to inhospitable areas of land that had until then been populated and plentiful.

But human causes suffice. Although only five centuries separate us from the date of Angkor's abandonment as capital, it should not be forgotten that a hard and far less glorious time followed the four century period - from the 9th to the 13th - of her splendour. Already exhausted by builder kings seeking to ensure their posthumous glory, the Khmer people could no longer offer resistance to a series of bloody wars followed no doubt by the systematic transfer of the population to slavery. Ruin came, but not total extinction.

CAMBODIA AND THE CAMBODIANS

The geographical framework of the ancient Khmer empire is reflected in that of its monuments. Although these are found grouped in a particularly dense manner in the Angkorian region to the north of the Great Lake, one can however include in totality more than a thousand remains scattered over the whole of the area between the gulf of Siam and Vientiane on the one side and between the Mekong delta and the valley of Menam on the other - that is to say in Cambodia itself, the major part of Cochinchina, lower and middle Laos, eastern Siam and a part of the Menam valley. The changes that occurred over the centuries came not from any lack of unity in the population, but rather from a contrast of a physical nature between the dry regions to the north of the chain of the Dangrek mountains and the fertile plains to the south.

Present day Cambodia is found bordered by the Gulf of Siam to the south-west, Laos to the north and Vietnam to the east and south-east. Its main artery is the Mekong valley, which crosses from north to south. This is joined at Phnom Penh by the Tonle Sap, spreading to the north-west in a large plain of water that extends for some 140 kilometres by 30 and irrigates the surrounding plains.

The Tonle Sap - once a maritime gulf that now forms a lake - has the peculiarity that each rainy season, from May to October, its waters are no longer able to flow into the flooding Mekong and become choked, rising by ten metres and so forming a huge regulatory basin, whose surface area triples that of the dry season. Large water festivals with canoe races during November's full moon mark the end of this period, and the King, in a symbolic ritual, presides over the reversing of the current.

Each annual deluge sees the Tonle Sap rise still further, completely flooding the forested zones that border its banks and ensuring a particularly abundant source of nourishment to its fish - so making it the richest fish pond in the world.

Cambodia lies between 10 and 14 degrees latitude north, and the climate nears the equatorial with an almost constant temperature. The contrast between the dry season and the season of the heavy rains is, however, quite marked, and although the average temperature of the year is 28 degrees, the nights of December and January - that are particularly fresh - see the temperature fall to around 20 degrees, while the months of April and May are distinguished by a torrid heat reaching 35 degrees in an atmosphere charged with storms which never break.

Although under the influence of the monsoons, the country is protected from the coast by chains of mountains ranging from 1000 to 1500 metres in height - notably the Elephant mountains, where the Bokor altitude station is located - giving it a less humid and unhealthy climate than Cochinchina. Here the skies are often quite fresh and clear - and extremely favourable to moonlit nights.

With its eight million inhabitants for an area of 180,000 square kilometres, Cambodia is an under-developed country with little cultivation. Thin agricultural resources are complemented with fishing, a little rearing of cattle and some forestry, while a large part of its area is mostly covered with unbroken forest and bush, and remains deserted.

Rice and fish are the staple diet, and the harvest is regulated by the rhythm of the rains and floods. The fish are plentiful - even in the paddy fields where they hibernate in the underground mud during the dry months to re-emerge with the first rains. On the Tonle Sap, during the dry season, entire villages are established on the open lake - their belongings suspended from poles with the racks of drying fish.

The rural Cambodian lives a rudimentary existence, by the water if possible, in straw huts or in wooden houses raised from the ground on posts of two metres in height. He is sheltered from the animals and the floods and keeps his meagre livestock under his home. With just enough work to be able to pay his taxes and support his family he lives preferably in the middle of his small-holding, and, without much of a taste for business, is content to let the Chinese or Vietnamese deal with the surplus produce from his paddy or sugar palm, pigs, chickens or the fruits of his garden.

The extensive crossbreeding over the centuries - the happiest of which has resulted, particularly in the towns, from a mixing with the Chinese - does not appear to have fundamentally changed the nature of the people. Cambodians are broad and muscular (standing on average 1m.65), are brachycephalic and generally dark in colour. The nose is broad, the lips are thick and the eyes straight and fairly narrow. The hair is worn short, even on the women. When they feel that one shows them some interest, they are hospitable and sweet natured.

Sensitive and religious, the family centres its life on the pagoda, where the male youth is obliged to spend some of his time. Generous towards their priests - the innumerable monks whose bright orange robes animate the landscape and to whom subsistence is readily assured - they take every opportunity to venerate the Buddha and gain merit, marking the year with numerous festivals to satisfy a distinct taste for leisure.

The national religion is Buddhism of the Small Vehicle, or Theravada, of the Pali language - which is also practised in Ceylon, Burma, Thailand and Laos. The monastic life here plays the principal role and the popular faith, while rudimentary and sometimes tinted with remains of ancient superstition, is based on the transmigration of the soul and the search for personal salvation through work during the course of an existence in which each action is accounted for in the regulation of the future. After death the body is carried to the pyre, and the cremation ends with either the deposit of the ashes in a small funerary monument (Cedei) or their scattering on sacred ground.

Ancient CambodiaOur knowledge of ancient Cambodia derives from three sources; - the interpretation of the bas-reliefs, the writings of Chinese travellers and the reading of the inscriptions on stone. Nothing remains of the tinted parchment manuscripts, written in chalk, or the latania leaves on which the inscribed characters were blackened with a pad. These essentially perishable records were able to resist neither fire, the humidity nor the termites.A. THE BAS-RELIEFS

The scenes sculpted on the bas-reliefs - in particular at the Bayon - often show almost exactly, if one has the time to study them closely, a picture of daily rural life that has barely since changed. One can see there the same kinds of dwellings, the same carts or canoes, the same costumes, the same instruments for cultivation, hunting, fishing or for music, the same habits and the same manual trades.

B. THE CHINESE CHRONICLES

The most complete of the Chinese chronicles - and the most descriptive - are those of Tcheou Ta-Kouan who, in 1296, just after the first wars with the Siamese and at the beginning of the period of decadence, accompanied a Sino-Mongole envoy to Angkor. His "Memoirs on the Customs of Cambodia", translated by Paul Pelliot and published in the Bulletin of the École Française d'Extrême-Orient of 1902, give an idea of the conditions of life in Cambodia at the end of the 13th century. He says of the inhabitants:

"The customs common to all the southern barbarians are found throughout Cambodia, whose inhabitants are coarse people, ugly and deeply sunburned. This is true not only of those living in the remote villages of the sea islands, but of the dwellers in centres of population. Only the ladies of the court and the womenfolk of the noble houses are white like jade, their pallor coming from being shuttered away from the strong sunlight.

"Generally speaking, the women, like the men, wear only a strip of cloth, bound round the waist, showing bare breasts of milky whiteness. They fasten their hair in a knot, and go barefoot - even the wives of the King, who are five in number, one of whom dwells in the central palace and one at each of the four cardinal points. As for the concubines and palace girls, I have heard that there are from three to five thousand of them, separated into various categories, though they are seldom seen beyond the palace gates. When a family has a beautiful daughter, no time is lost in sending her to the palace.

"In a lower category are the women who do errands for the palace, of whom there are at least two thousand. They are all married, and live throughout the city. The hair of their forehead is shaved high in the manner of the northern people and a vermilion mark is made here and on each temple. Only these women are allowed entry to the palace, which is forbidden to all of a lesser rank.

"The women of the people knot their hair, but with no hairpin or comb, nor any other adornment of the head. On their arms they wear gold bracelets and on their fingers, rings of gold - a fashion also observed by the palace women and the court ladies. Men and women alike are anointed with perfumes compounded of sandalwood, musk and other essences.

"Worship of the Buddha is universal...".

C. THE INSCRIPTIONS

The epigraphy is less anecdotal in nature and describes the other Cambodia, particularly its history, offering a more serious documentation. Together with the studies in the history of art it has enabled the accurate dating of the monuments.

Inseparable are the names of Barth, Bargaigne, Kern and Aymonier, then of Louis Finot and of Georges Cœdes, all of whom dedicated themselves to their task with an impressive methodology and a rigorous discipline. Due to the number of discoveries their science soon became of major importance.

The earliest known inscriptions date from the 7th century and relate to the central Indian "Saka" era. Later than the Christian era by 78 years, this must have been introduced to the Indian Archipelago and Indo-China by Hindu astronomers.

"From the beginning" - we are told by Mr Cœdes - "they simultaneously used two languages - a scholarly language, Sanskrit, reserved for the genealogy of royalty or dignitaries, for the panegyric of the monuments' foundation or for that of the revered donors - and a common language, Khmer or Cambodian, reserved for the disposition of the foundation and the listing of servants or objects donated to the temple. Sanskrit texts are only written in verse: these are the compositions that the Indians call 'Kavya'".

Sanskrit ceased to be the scholarly language used in Indochina when, towards the 14th and 15th centuries, the Brahmanic and Mahayana (or Large Vehicle) Buddhist religions were replaced by Hinayana (or Small Vehicle) Buddhism, and the language used became Pali, also of Hindu origin. As for the old Khmer, Mr Cœdes remarks that "it differed far less from present day Cambodian than the language of Chanson de Roland differed from French".

The inscriptions were engraved with a burin or etcher's chisel in letters of less than a centimetre in height on steles, on tablets and on the door openings of the sanctuaries. The steles, whose location varied between monuments, generally stood in a special shelter, either as rectangular slabs with two inscribed faces or as bornes with four sides, in a hard, polished stone and fixed to the ground or to a base by means of a tenon. Many were found in open countryside.

The text on the jambs of the door openings often covered most of their surface. Towards the end of the classic period it became usual to recount in one or many lines the setting of a statue - a god or a divinity - in the sanctuary, either in reserving a smooth place in the decorative surface of the stone or in scraping a patch clear: this is also true for the identification of certain scenes in the bas-reliefs. Finally, on many of the blocks, roughly inscribed characters can be seen which must have been made by the masons.

HistoryChinese texts first referred to Fou-Nan, in the first denomination of what was later to become the kingdom of Cambodia, at the beginning of the Christian era - then little advanced since, in the 3rd century, "the people of the country were still naked". In its geographical location, however, it was the natural stop-over between India and China, and this contact with the two large Asiatic civilisations was to assure its rapid transformation with the impression of their double influence.

From the 3rd to the 5th century the clearly Hindu kingdom of Fou-Nan acquired a large territorial boundary - whose dynastic traditions Mr Cœdes attributes to the court of the Pallavas - establishing the capital in the region of Ba Phnom in the south-eastern part of present day Cambodia. Rich and powerful, it maintained steady relations with the Chinese - a fact proven by numerous ambassadorial missions.

Towards the middle of the 6th century, however, the feudal states became unsettled, and the most powerful of them, the Tchen-La or Kambuja (Cambodia as such), proclaimed its independence and gradually enlarged - to Fou-Nan's disadvantage - to eventually take her capital after three quarters of a century of battle during the life of Isanavarman. Gaining the throne around 615, he reigned until 644 and founded the new capital of Isanapura - probably at Sambor-Prei Kuk near Kompong Thom.

A little afterwards, and for the whole of the 8th century, the kingdom divided into two rival states; - the coastal or lower Tchen-La, comprising Cochinchina and the lower Mekong basin to the south of the chain of the Dangrek mountains, - and the inland or upper Tchen-La corresponding to the territories situated to the north of these as far as upper Laos. During this period the lower Tchen-La suffered invasion from Java and Sumatra, where the Malayan empire of Shrivijaya had become powerful. Indeed from Java, at the beginning of the 9th century, came the king - evidently there in exile - who was to re-establish the unity of the kingdom and initiate the so called "angkorian" period.

Appealing to the ancient dynasties he ruled under the name of Jayavarman II, and, proclaiming Cambodia's independence from Java, began to investigate a site for his capital - no longer in the lower Mekong basin, but in the region to the north of the Great Lake or Tonle Sap. After a trial period on the plain he cast his interest to the chain of the Mahendra (Phnom Kulen) which, with its vast eastern plateau of 10,000 hectares, offered remarkable conditions for defence against invasion. It was therefore here that, in the year 802, he established the siege of his State and laid the foundations for a new cult - that of the god king or Devaraja - by establishing, on his pyramid of Rong Chen, the first Royal Linga.

After fifty years of reign that had allowed him to unify the country, Jayavarman II, perhaps discouraged by the difficulties of access and the poor potential for the cultural development of the settlement he had chosen - and its distance from the Great Lake - descended once again to its northern shores. He died around 850 at Hariharalaya, the region of Roluos also adopted by first his son and then his nephew, Indravarman I. It was this king who built the artificial pyramid of Bakong - the first sandstone monument - and founded there in 881 the linga Shri Indresvara.

In the last few years of the 9th century, his son Yasovarman, judging his power to be sufficiently stable and seeking to create something of more permanence, finally abandoned the temporary nature of the nomadic settlement to create a veritable "puri", with defined limits and endowed with all the prestige of a capital worthy of its name. This was Yasodharapura, the first Angkor, where the "Vnam Kantal" or "Central Mount" of the inscriptions - identified after fervent research by Mr Goloubew with the hill of Phnom Bakheng - served as a base for the linga Shri Yasodharesvara, the master idol of the kingdom.

Angkor was to remain the capital during the following centuries of battle and glory, except for a period of 23 years from 921 to 944, when the king moved to Chok Gargyar (Koh Ker), a hundred kilometres to the north-east. His nephew Rajendravarman returned to Angkor and "restored the holy city that had long remained empty", building the temples of the eastern Mebon and of Pre Rup, and leaving for war with Champa where he sacked the temple of Po Nagar.

Around the 11th century, at the time when the temples of Ta Keo, Phimeanakas and the Baphuon were being built, it seems that the limits of the city were modified and that, by shifting slightly to the north, it no longer had Phnom Bakheng as its centre, but corresponded noticeably thereafter to the layout of the future Angkor Thom. During this period a foreign dynasty took the throne. Perhaps of Malayan origin, the usurper - Suryavarman I - soon enlarged the kingdom to encompass the whole southern part of Siam or Dvaravati.

The first half of the 12th century was dominated by the reign of one of the principal kings of Cambodia - Suryavarman II - whose immense architectural realisation of Angkor Wat was to mark the apogee of classical Khmer art. After having being allied with the Chams against the Annamites (Vietnamese) he then turned against them, winning a brilliant victory and gaining part of Champa.

Revenge was not long in coming, and a period of troubled times followed the death of the king, some time after 1145. Power was again seized by an usurper, and in 1177 a surprise attack by the Chams ended in the fall and the sacking of Angkor, followed by general devastation.

The invader, however, subject in his turn to a complete defeat, was expelled by Jayavarman VII who was crowned king in 1181 at the age of about 55. Champa was put under the control of the Khmer and governed by the brother-in-law of the victor who, following his conquests, then extended his power as far north as Vientiane on the Mekong and west to the basin of the Menam.

At the same time and with prodigious activity, Jayavarman VII raised Cambodia from its ruins and reconstructed its capital Angkor Thom, surrounding it with a high wall breached by five monumental gates - he rebuilt the central temple of the Bayon, built or restored to completion the monuments of Prah Khan, Ta Prohm and Banteay Kdei, as well as others of less importance, and furnished the country with numerous hospitals.

Such effort, coming after so many bloody battles, could not but drain the facilities and energy of the nation - so that from the beginning of the 13th century, after the death of this last great king, the Khmer people fell to inertia. Gradually its princes were stripped first of their ancient conquests by their Thai neighbours, and then of their heritage. Already in 1296 the Chinese envoy Tcheou Ta-Kouan gave some indication of this growing pressure, which must have resulted in the 15th century abandonment of Angkor and the establishment of the Cambodian kings on the banks of the lower Mekong.

To continue with the history of Cambodia from this time would be to leave the bounds of this study, since the period from the 15th century to modern times has little to offer the history of archaeology. The regions of Siem Reap and of Battambang, annexed with no right by the Siamese, were restored to Cambodia in 1907. The year 1907 is not only a date of political importance - it is also since this restitution that the French scholars and architects, encouraged by the sovereign who succeeded to the throne, have been able, by methodical research and the precise technique of anastylosis, to revive the ancient relics of a glorious civilisation.

ReligionThe religious history of ancient Cambodia is founded on syncretism. From the time of Fou-Nan until the 14th century, Brahmanism and Buddhism - the two great Indian religions - co-existed. Imported to Indochina at the latest towards the beginning of the Christian era, their dual influence is evident time and again in angkorian architecture and epigraphy.

The Khmer kings, while not seeking to impose their personal beliefs, generally seemed to have shown great religious tolerance. Sylvain Levi moreover makes the observation that the two religions, originally foreign to the country, must rather have seduced the middle aristocracy as the manifestation of an elegant and refined culture than to have penetrated to the depth of the masses. Even now there remains a caste of priests - the "Bakou" - who carry the Brahmanic cord. Practising the official religion they play an important role, guard the sacred sword and preside at certain traditional festivals.

This fusion of the two religions did not however preclude occasional acts of fanaticism, manifest in the systematic mutilation of the stone idols that were butchered with the carvers tool or re-cut to suit the form of the opposing faith - the stele of Sdok Kak Thom describes for instance how "king Suryavarman Ist had to raise troops against those who tore down the holy images", while in the 13th century there was a relentless and violent Shivaïte reaction against the works of Jayavarman VII.

The oldest known known archaeological remains in Fou-Nan are Buddhist, suggesting that Buddhism probably preceded Brahmanism. If so, then this would have been in the form of Hinayana or the Small Vehicle (though in Sanskrit) rather than Mahayana or the Large Vehicle. Not appearing in any certain manner until the end of the 7th century, this latter must have gained favour during the angkorian period in parallel with the official Brahmanism, which usually predominated.

At the dawn of the 9th century, the accession to the throne of Jayavarman II - from Java - and the establishment of his capital in the region to the north of the Tonle Sap was to mark the establishment of a new cult that was to continue until the decline of the Khmer empire - that of the Devaraja or the god-king, symbolised in the linga that was considered as an incarnation of Shiva.

Set on a "temple-mountain" or a tiered pyramid raised at the centre of the capital, this image must have been revered in the residence itself of the living king. The inscription of Sdok Kak Thom again gives us the filiation of a whole family of priests who, for more than two centuries, were responsible for maintaining the observation of the newly established ritual.

In Cambodia there was also the privilege of apotheosis, which could benefit not only the king but also certain figures of high delineage - sometimes even during their lifetime - from where came the use of the "posthumous names" indicating the celestial abode of the deceased monarch, each one being assimilated to his chosen god.

Towards the end of the 12th century, the Buddhist king Jayavarman VII, in order to assure perpetuity to the symbolic cult of the Devaraja, instituted the similar cult of the Buddha-king at the Bayon - the central temple of Angkor Thom - manifest in the portrait statue that was found broken at the bottom of the well (and which has now been restored). This form of adaptation, however, was not to last, and from the 13th century, following a return to Shivaïsm, the Buddhism of the Large Vehicle - of the Sanskrit language - was replaced by that of the Small Vehicle - of the Pali language - to which Cambodia has remained faithful.

HINDU BELIEFS

"While for other human beings" - we are told by Sylvain Levi - "senses are witnesses that provide unquestionable assurance, for the Hindu they are but the masters of error and illusion.... The vain and despicable world of phenomena is ruled by a fatal and implacable law - each act is the moral result of a series of immeasurable earlier acts, and the point of departure for another series of immeasurable acts which will be indefinitely transformed by it... Life, when so considered, appears as the most fearful drudgery - like an eternal perpetuity of false personalities, to come and to go without ever knowing rest. So the sovereign perhaps then became none other than the Deliverance, the sublime act by which all causative forces became eliminated, and which ceased once and for all for a system given the creative power of the illusion."

Such is the framework in which the two main Indian religions were to develop. Introduced to Cambodia it would seem evident that in their transcendent form they could only touch an elite, and were never to penetrate to the masses. The crowds, when admitted to enter the temples, came not in order to worship some or other god of the Hindu pantheon, but rather to prostrate themselves before their duly deified prince or king.

BRAHMANISM

Brahmanism appeared in India several centuries before Christ and was itself derived from Vedism, based on the adoration of the forces and phenomena of nature. Determined by the "Brahmana", its ritual is strongly coloured with symbolism and associated with a particularly crowded polytheism.

At its summit is the "Trimurti", the supreme trinity that synthesises "the three active states of the universal soul and the three eternal forces of nature. Brahma, as activity, is the creator, - Vishnou, as goodness, is the preserver, - and Shiva, as obscurity, is the destroyer" (Madrolle).

BRAHMA

In India, as in Cambodia, Brahma has never been a primary divinity despite his apparent supremacy as creator of the world. He is represented with four arms and four opposing faces, two by two, symbolic of his omnipresence. Sometimes he is seated on a lotus whose stem grows from the navel of Vishnou, reclining on the waves. His wife or feminine energy ("sakti") is Sarasvati, and his mount is the sacred goose or "Hamsa" - "whose powerful flight symbolises the ascension of the soul to liberation" (Paul Mus).

Vishnou and Shiva, on the other hand, predominate. After having been associated with Vishnou in the same image during the pre-angkorian period - split by half vertically in the form of Harihara - Shiva initially clearly prevailed. Towards the end of the 11th century until the time of Angkor Wat, however, it would seem that he was ousted by Vishnou.

VISHNOU

Vishnou, the protector of the universe and of the gods, generally stands with a single face and four arms, carrying as attributes the disc, the conch, the ball and the club. His wife is Lakshmi, the goddess of beauty. One can often see her between two elephants who, with raised trunks, spray her with lustral water. The mount of the god is the sun bird, Garuda, who has the body of a man and the talons and beak of an eagle and is, as genie of the Air against the genies of the Waters, enemy since birth of nagas or serpents.

In the form of the Brahman dwarf Vamana, Vishnou crosses Heaven, the Earth and the intermediate atmosphere in three steps to assure possession of the world to the gods. Between each cosmic period (Kalpa), while the world sleeps, the god slumbers on the serpent Ananta, carried by the ocean waves. On awakening he is reincarnated, as man or beast, to triumph over the forces of evil, each time starting a new era. These are the "avatars", or the descents of the god to earth, the principal of which number a dozen.

THE AVATARS OF VISHNOU

In the form of the tortoise, Vishnou participates in the popular "Churning of the Ocean", taken from the Bhagavata Pourana and common in iconography - the gods and the demons dispute the possession of the amrita, the elixir of immortality, and the tortoise serves as a base for the mountain forming a pivot.

As the man lion, Narasimha, Vishnou claws the king of the Asuras, Hiranya-Kasipu, who dared to challenge his supremacy.

But in particular it was Rama and Krishna, the two human incarnations of whom the Indian poets wrote, that provided the sculptors of the walls and frontons of the temples with an endless supply of subject matter. The two main epics of the Ramayana and of the Mahabharata, we are told by Keyserling, "are to the Hindus what the Book of Kings was to the exiled Jews - the chronicle of a time when they were a force to be reckoned with on earth while also in closer contact with the celestial powers." They were devoted to the legends because "they had no sentiment about historical truth - for them the myth and the reality were but one and the same. Soon the legend is judged as reality and the reality condensed in the legend. The facts by themselves are irrelevant".

Krishna remains quite human. Exchanged as a child he escaped death at birth to lead a bucolic existence in the forest. Of Herculean strength, he drags a heavy mortar stone to which he has been attached by his step mother, felling two trees along the way. As an adolescent of great beauty he charms the shepherds and shepherdesses and protects them and their flocks from a storm by raising mount Govardhana with one arm. Mounted on Garuda he triumphs in his battle against the asura Bana, but generously spares the asura his life at Shiva's will.

It is at the request of the gods, who urge him to rid the world of the demon Ravana, that Vishnou manifests himself as Rama, son of the king of Ayodhya. Winning a contest in which he has to shoot a bird behind a moving wheel with an arrow, he gains the hand of the beautiful Sita, the adopted daughter of the king of Mithila. Then sadly exiled by her father he goes, with his brother Lakshmana, to live as an ascetic in the forest, accompanied by his wife. There they are subject to attack by the rakshasas. Sita, first saved from the hands of one of them, Viradha, is then taken by their king Ravana - particularly menacing with his multiple arms and heads - who carries her to the island of Lanka (Ceylon) while the two brothers are lured by an enchanted gazelle with a golden coat. Alerted by the vulture Jatayus, who tries in vain to prevent the kidnapping, they set off to recover Sita, meeting with the white monkey Hanuman who takes them to his king Sugriva - whom they find grieving in the forest, having been ousted from his throne by his brother Valin. They form an alliance with him. Valin is killed by an arrow from Rama during a struggle, and Sugriva, heading his army, leaves for the attack of Lanka.

Hanuman, who is sent ahead to investigate, finds the despondent Sita in the grove of asoka trees where she is guarded by the rakshasis (female demons) and exchanges a ring with her to prove the success of his mission to Rama. He leaves, but not before torching the palace of Ravana, and the monkeys, having first constructed a dike to cross the channel of water separating them from their enemies, begin the multiple episode struggle - with the furious scrum dominated by the duel between Ravana on his chariot drawn by horses with human heads and Rama, also mounted on a chariot or on the shoulders of Garuda. A son of Ravana, the magician Indrajit, restrains Rama and Lakshmana with arrows which transform into serpents and encoil them - but Garuda, swooping from the sky, saves them. Victory finally goes to Rama, who rescues the unhappy Sita. However, suspected of being corrupted, she is put to the test of fire. Proven innocent by this ordeal she is solemnly returned by the god of fire, Agni, to her husband - who is finally restored to the throne of his fathers.

SHIVA

In the Trimurti it is Shiva who, with Brahma at his right and Vishnou at his left, has to be considered as the supreme god, of whom the others are but the emanation and reflection.

Sometimes he is the great destroyer, the genie of the tempest and of destructive forces - though more so in India than in Cambodia, where he is rarely presented in a bad light - while elsewhere as the protector he is benevolent, the god who conceives and creates. He is also the first of the ascetics, going naked to rub himself in the cinders of a dung fire, living on charity and practising meditation - the source of perfection.

In his human form he usually has a single face with a third eye placed vertically in the middle of the forehead and his hair raised in a chignon, showing a crescent - but he sometimes also has multiple heads. His arms likewise vary in number, his principal attribute is the trident and his torso is crossed with the Brahmanic cord. He determines destiny with his dance - the frenetic rhythm of the "tandava". His sakti or feminine energy can also herself be sweet or ferocious - sweet she is Parvati, the goddess of the Earth, or Uma, the Gracious, whom one can often see sitting on Shiva's knee when he is throned on mount Kailasa or riding his usual mount, Nandin the sacred bull - ferocious, she is Durga the Aggressor who, with her lion, overcomes the demon buffalo.

The cult of Shiva is no less reserved - particularly in its symbolic representation, the creative power expressed by the "linga" - though there is no particular reason to dwell upon the phallic nature of this image which, for the oriental spirit, goes far beyond questions of human sexuality.

The linga is formed in a cylinder of carefully polished stone, with rounded corners at its top, rising from a base that is first octagonal in section and then square. It represents, according to the legend, the sheath of Vishnou (octagonal), and then of Brahma (square), protecting the earth from contact with the sacred pillar which, descending from the sky as a column of flame, would drive itself into the soil. Only the cylindrical section projects from the pedestal. This is covered with a channelled stone (snanadroni) that has a projecting beak forming a gully that is always orientated to the north. The priest anoints it with lustral water which flows over it in a symbolic ritual destined to bring rain and fertility to the lands.

From the union of Shiva and Parvati are born two sons - Skanda, the god of war whose mount is the peacock or the rhinoceros - and Ganesha, the god of initiative, intelligence and wisdom. Popular in Cambodia, he has the head of an elephant and the body of a man - usually plump and coiled with the Brahmanic cord. Normally seated, he dips his trunk into a bowl resting in one hand, while with the other he holds the tip of one of his broken tusks. His mount is the rat. Legend has it that, originally a handsome young man, he was one day standing guard at his mother's door and prevented his father from entering who, enraged, decapitated him. At the insistence of Parvati, Shiva consented to give him the head of the first living being that presented itself - which was an elephant.

INDRA AND SOME SECONDARY DIVINITIES

An ancient superior god of vedism, Indra remained the principal of the secondary divinities. He is sieged in paradise on the summit of Mount Meru and, armed with a thunderbolt or "vajra", he rouses the storms that generate the life-giving rains. His mount is Airavana, the white elephant born of the churning of the Sea of Milk, who generally has three heads.

Kama

The god of love, he is a handsome adolescent with a sugar cane bow and lotus stem arrows. His spouse is Rati and his mount is the parrot.

Yama

The Law Lord or supreme judge, who presides over the underworld. He is mounted on a buffalo or rides an oxen drawn chariot.

Kubera

The god of riches, he is dwarfed and deformed. He is commander of the "Yaksha" or Yeaks, the grimacing giants with bulging eyes and prominent fangs that one finds particularly as dvarapalas or guardians, armed with clubs at the sanctuary doors.

Finally are the countless demigods, found in profusion in the decoration of the temples. Amongst others are the benevolent deva, eternally in battle with the asura, ogres and demons - the apsaras, flying celestial nymphs, born of the Churning of the Sea of Milk, they animate Indra's sky with their dancing - there are also the devata of the bas-reliefs who stand, richly adorned and motionless, holding flowers - and the nagas, the stylisation of a multi-headed cobra, descendants of Nagaraja, the mythical ancestor of the Khmer kings, and genies of the water.

BUDDHISM OF MAHAYANA OR THE LARGE VEHICLE

It would be wrong to believe that the first Buddhism eliminated the preceding divinities of the Brahmanic pantheon - quite the contrary - for the most part it assimilated them, though giving them a role that was secondary to that of the Buddha. The conquest however was more apparent than real, and in India soon became a cause of weakness.

"The Large Vehicle" - we are told by Madame de Coral-Remusat - "develops the supernatural aspect of the Buddha - it involves a whole pantheon of bodhisattvas or future Buddhas, then the Dhyani-Bouddhas or Buddhas in Contemplation. To the belief in Nirvana, advocated by the Hinayana, the Mahayanists add an infinite Paradise - the "Pure Earth" where the soul is reborn according to its merit".

The "Lotus of the Good Law", the canonical reference, describes the genesis of the formation of these bodhisattvas who are the saints of the new religion. Arriving at the very threshold of Nirvana through meditation and understanding, they defer their own deliverance in order to dedicate themselves to the salvation of others through teaching.

In Cambodia, Avalokitesvara or Lokesvara is the spiritual son of the transcending Dhyani-Buddha Amitabha - the image of whom he carries on his chignon. He personifies, as Paul Mus has explained "the notion of providence, unknown to primitive Buddhism". He is the "Lord of the World" from whom all gods emanate, himself the god of morality and graciousness - a masculine replica of Kouan-Yin, the other dominant figure in far eastern Buddhism. His attributes are often comparable to those of Shiva. Sitting or standing on a lotus blossom that elevates him above the world, he generally has four arms. His attributes are the flask, the book, the lotus and the rosary - but the number can vary from two to six or twelve and more. The face often has a third eye on the forehead and the heads can be multiple and in tiers. In the living architecture of the towers of the Bayon, by the turning of his four faces to the four cardinal points, he is omnipresent.