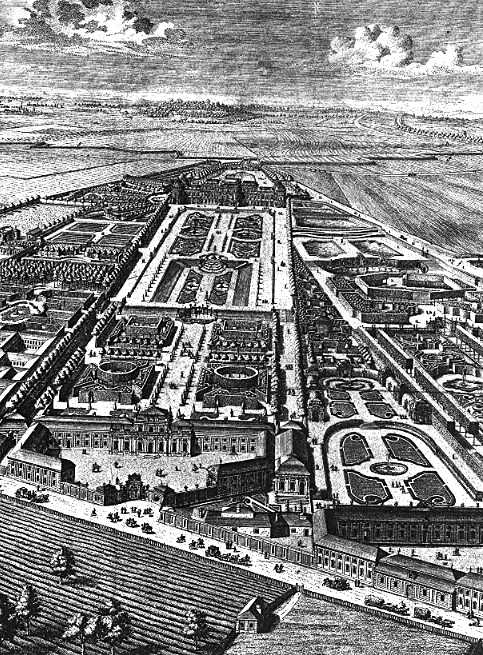

"The early eighteenth century was in the hands of princes and prelates whose wealth and ambitions were reflected in masterpieces commissioned to celebrate the pomp and splendor of their reign. Marvels of a dizzying grandeur were created in an exuberantly ornate style designated as Rococo."

"More discreetly, abbots, bishops and archbishops, often of royal lineage, sought to offer God and His followers palaces expressing their faith in ecstatic, even voluptuous, terms."

During the 1985/86 autumn/winter semester, Jacques-Edouard Berger gave a lecture series entitled "Baroque and Rococo Splendors". For the purposes of this program, we have chosen the lecture he gave on February 11, 1986 - "Rocaille and Rococo II: the putti's dance-in-the-round in honor of the greatness of God" - as an attempt to pay tribute to the great art historian that he was. Indeed, beyond sparking enthusiasm for art in general, it was in that role that he inspired appreciation for what, still today, is all too frequently considered a bastardized art movement, namely the Rococo style. What Mannerism is to the Renaissance, Rococo may be to the Baroque. In any case, Rococo inspired a virtuoso explosion with felicitous consequences for those princes and bishops who could indulge in the luxury of building or transforming their palaces and churches. Besides the greats of the period known to everyone, such as Caravaggio or Bernini, our overview highlights less familiar names such as Bergmüller and Sturm, to mention but one each of that era's great painters and sculptors. Let us now discover these marvels.

"travelling on to the gently sloping dales of Bavaria, where swarms of stucco putti joyously extol the divine order".

Truus et Philippe Salomon-de Jong, février 1997.

Quite to the opposite of the Rococo soul, the soul of the Baroque is characterized by austerity that inspires silence and meditation. By the same token, it is the aesthetic nature of the Baroque to underscore the basic lines and points of the message being conveyed. To visualize this, we have chosen several 17th-century paintings that stage the silence of the Baroque.

The basic theme of silence is vividly portrayed in the range of works going from Caravaggio to Georges de La Tour, for instance in the latter's

Magdalene with the Smoking Flame Another striking example is Magdalene Meditating, an early 17th-century work from the Neapolitan school. Following in the wake of Caravaggio, this school of silence would spread far and wide across Europe.

Another striking example is Magdalene Meditating, an early 17th-century work from the Neapolitan school. Following in the wake of Caravaggio, this school of silence would spread far and wide across Europe.

Claude Meylan's "Salomé" provides still another depiction of silence, of the most fundamental of dialogues (that of Life and Death). This work illustrates the repercussions of the message left by Caravaggio, a message of what is intrinsic to man, in a painting that - in the light-and-dark contrasts of grays surrounding the face of Salome - conveys the latter's newly awakened horror at the sacrifice of John the Baptist. During the Baroque period, this concern with the essence of life is to be found even in works by the more mundane artists. Indeed, among the mundane greats on the Baroque scene, it had become the fashion to adopt an economy of means, in an endeavor to attain a more informal intimacy, to create works of a more confidential tone. This can be seen, for instance, in Guido Reni's "Saint Joseph and Child", a work that, although unacclaimed by the contemporary world, did have its hour of glory during the 17th century. And why was this so? Because, at the time, Reni was far more famous than all the Caravaggios and La Tours of the world, who have since been rediscovered. Reni represented a high point in Baroque art history. Moreover, in this work he allowed himself the luxury of tackling an extremely rare subject. The very strangeness of its subject is what became its glory: instead of portraying Virgin and Child as was generally the case, it stages father and Child. Although renowned in particular for his bright colors and the elegance of his compositions, here Reni nevertheless sought to rein in the methods of his art the better to convey the intrinsic nature of this father-Child dialogue.

The great aesthetic impact of the Baroque made itself felt all the more in works dealing with such serious subject matter as the Christian epic. In this vein, the Pietà (Virgin Mary mourning over the dead body of Christ) was one of the major themes to be broached, precisely because, here again, Life and Death are allied. The theme involves a perspective of day and night, corresponding with the light-and-dark philosophic mood marking the entire 17th century. The Baroque approach to the Pietà centered on the theme's dramatic essence, as beautifully illustrated in the work of Andriaen van der Werff, a painter who, notwithstanding his Flemish origin, made a career for himself in Italy. Van der Werff's Pietà is entirely in black and blue: everything other than the Virgin's cloak - that is, everything other than this symbol of life - is painted in a camaïeu ranging from white to black, from the body of Christ to the darkness of the background.

Another stunning example is to be found in the Pietà of the Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Piazzetta: the light marking the great arch stretching the corpse in the foreground drives back the darkness, from where the work's feminine central figure seems to burst forth. Here again, the play of light and shadow translates a fundamental dialogue and, as such, proves itself intrinsically Baroque. These few examples of the 17th-century school of painting ranging from Caravaggio to Piazzetta illustrate an approach that was severe and contemplative, focussing on silence, on the essence of life. It was only natural for this same approach to carry over to Baroque architecture, which can thus also be characterized as austere and basic. To illustrate our point, we refer to the Il Gésu church in Rome, where the choir, realized (between 1678 and 1680) by Carlo Rainaldi, a pupil of Bernini, features an outstanding dialogue between horizontals and verticals: the great horizontal of the entablature contrasts with the verticals of the pillars supporting the play of perfect arches (as in the apse, the dome, and even the lantern). Rainaldi's choir beautifully exemplifies the economy of means that is a signature feature of the Baroque spirit.

Another striking example is Magdalene Meditating, an early 17th-century work from the Neapolitan school. Following in the wake of Caravaggio, this school of silence would spread far and wide across Europe.

Another striking example is Magdalene Meditating, an early 17th-century work from the Neapolitan school. Following in the wake of Caravaggio, this school of silence would spread far and wide across Europe.

Claude Meylan's "Salomé" provides still another depiction of silence, of the most fundamental of dialogues (that of Life and Death). This work illustrates the repercussions of the message left by Caravaggio, a message of what is intrinsic to man, in a painting that - in the light-and-dark contrasts of grays surrounding the face of Salome - conveys the latter's newly awakened horror at the sacrifice of John the Baptist. During the Baroque period, this concern with the essence of life is to be found even in works by the more mundane artists. Indeed, among the mundane greats on the Baroque scene, it had become the fashion to adopt an economy of means, in an endeavor to attain a more informal intimacy, to create works of a more confidential tone. This can be seen, for instance, in Guido Reni's "Saint Joseph and Child", a work that, although unacclaimed by the contemporary world, did have its hour of glory during the 17th century. And why was this so? Because, at the time, Reni was far more famous than all the Caravaggios and La Tours of the world, who have since been rediscovered. Reni represented a high point in Baroque art history. Moreover, in this work he allowed himself the luxury of tackling an extremely rare subject. The very strangeness of its subject is what became its glory: instead of portraying Virgin and Child as was generally the case, it stages father and Child. Although renowned in particular for his bright colors and the elegance of his compositions, here Reni nevertheless sought to rein in the methods of his art the better to convey the intrinsic nature of this father-Child dialogue.

The great aesthetic impact of the Baroque made itself felt all the more in works dealing with such serious subject matter as the Christian epic. In this vein, the Pietà (Virgin Mary mourning over the dead body of Christ) was one of the major themes to be broached, precisely because, here again, Life and Death are allied. The theme involves a perspective of day and night, corresponding with the light-and-dark philosophic mood marking the entire 17th century. The Baroque approach to the Pietà centered on the theme's dramatic essence, as beautifully illustrated in the work of Andriaen van der Werff, a painter who, notwithstanding his Flemish origin, made a career for himself in Italy. Van der Werff's Pietà is entirely in black and blue: everything other than the Virgin's cloak - that is, everything other than this symbol of life - is painted in a camaïeu ranging from white to black, from the body of Christ to the darkness of the background.

Another stunning example is to be found in the Pietà of the Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Piazzetta: the light marking the great arch stretching the corpse in the foreground drives back the darkness, from where the work's feminine central figure seems to burst forth. Here again, the play of light and shadow translates a fundamental dialogue and, as such, proves itself intrinsically Baroque. These few examples of the 17th-century school of painting ranging from Caravaggio to Piazzetta illustrate an approach that was severe and contemplative, focussing on silence, on the essence of life. It was only natural for this same approach to carry over to Baroque architecture, which can thus also be characterized as austere and basic. To illustrate our point, we refer to the Il Gésu church in Rome, where the choir, realized (between 1678 and 1680) by Carlo Rainaldi, a pupil of Bernini, features an outstanding dialogue between horizontals and verticals: the great horizontal of the entablature contrasts with the verticals of the pillars supporting the play of perfect arches (as in the apse, the dome, and even the lantern). Rainaldi's choir beautifully exemplifies the economy of means that is a signature feature of the Baroque spirit.

In total contrast to Baroque, the Rococo style dances, plays itself out completely. Its lilting tones sing with the passion of the castrati, glorifying God with the fervor of an entire era.

This very fervor comes through in the work of the Venetian painter

Jean-Baptiste Tiepolo

In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)

Caravaggio

Georges de La Tour

Guido Reni

Adriaen van der Werff

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta

Rainaldi

Giambattista Tiepolo

Filippo Juvarra

Carl-Philip von Greiffenclau

Eugene of Savoy

Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt

Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer

Rupert Neß von Ottobeuren

Schmuzer (also spelled Schmuzzer and Schmutzer)

Johann Georg Bergmüller

Johann Jakob Herkomer

Franz Xaver Schmädl

Ignaz Günther

Dominikus Zimmermann

Anton Sturm

Johann Effner

Johann Michaël Fischer

Josef Weinmüller

Johann Michael Feichtmayr (the Younger)

Karl-Eugen von Greiffenclau

, for instance in "la Montée au Calvaire (The Way to Calvary)" , one of the rare episodes of the Christian epic he chose to stage. What we see here goes counter to all that precedes it: gone from the scene are the dark-light essentiality, immobilism, silence and, above all, vital confidentiality between the viewer and the work. This work lives autonomously, exalting its own prowess, dancing and singing to its own glory.

Clearly, all the lines of this work progress upwards, towards the heights of Golgotha. The colors too - all the reds, blues, whites, golds, yellows, flesh colors in various shades - all progress upwards. The artist obviously enjoyed playing with space, producing something that is basically theatrical. In its contrast with the work of Caravaggio, Meylan, Guido Reni, van der Werff and Piazzetta, this painting serves as a masterful introduction to pictorial Rococo.

, one of the rare episodes of the Christian epic he chose to stage. What we see here goes counter to all that precedes it: gone from the scene are the dark-light essentiality, immobilism, silence and, above all, vital confidentiality between the viewer and the work. This work lives autonomously, exalting its own prowess, dancing and singing to its own glory.

Clearly, all the lines of this work progress upwards, towards the heights of Golgotha. The colors too - all the reds, blues, whites, golds, yellows, flesh colors in various shades - all progress upwards. The artist obviously enjoyed playing with space, producing something that is basically theatrical. In its contrast with the work of Caravaggio, Meylan, Guido Reni, van der Werff and Piazzetta, this painting serves as a masterful introduction to pictorial Rococo.

It also points the way to architecture: just as the Baroque paintings led us to the Il Gésu choir in Rome, so this painting by Tiepolo guides us to Rococo architecture, in particular as exemplified by Bavarian constructions. Here again, we will find ourselves far from the austere cult of the divine mystery. Instead, we will be confronted with works that translate a stylistic explosion accomplished with supreme mastery.

Name

Role

Caravaggio (1571-1610). Michelangelo Merisi da, called Caravaggio after the town from which his family came. Italian painter who revolutionized pictorial tradition with strong contrasts accenting the vivid realism of his scenes. Greatly influenced the development of European painting.

1593-1652 — French painter renowned for the unmistakable originality of his style: skillfully organized plays of light, austere realism, simplified volumes.

1575-1642 - Italian (Bolognese) painter.

Disciple of Carracci.

1659-1722 — Dutch painter.

1683-1754 — Italian (Venetian) painter, who had great influence on Tiepolo.

1611-1691 — Italian architect of the High Baroque.

1696-1770 — Italian (Venetian) painter, decorator, and etcher. In his large-scale frescoes, the great clarity of color and deft draftsmanship make his figures seem to "fly" in airy space.

1678-1736 — Italian architect (Late Baroque and Early Rococo).

Prince-Bishop of Würzburg.

1663-1736 — Prince of House of Savoy, general in the service of the Holy Roman Empire, notredfor his patronage of the arts.

1668-1745 — Austrian architect

1689-1751 — Bohemian architect (Late Baroque), who worked mainly in Prague where he finished (great dome and bell tower,1737-1751) the St. Nikolas Church of Mala Strana (Little Quarter), started by his father in 1703, and built St. Nikolas Church of the Old Town Square 1732-6.

24. November 1670 in Wangen im Allgäu; † 20. Oktober 1740 in Ottobeuren; auch Rupert II war der 52. Abt und Reichsprälat des Klosters Ottobeuren.

Brothers Franz (1676-1741), decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph (1683-1752, architect and decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph's son Franz Xaver (1713-1775), decorator/stuccoer

1688-1762 — Bavarian painter, teacher, printmaker and draftsman.

1648-1717 — Bavarian architect, painter, and stuccoer.

1705-1777 — Bavarian sculptor.

1725-1775 — Bavarian architect and wood carver.

1685-1766 — Bavarian architect.

1690-1757 — Bavarian sculptor and stucco artist.

1687-1745 — Bavarian architect (Munich court architect) and decorator.

1691-1766 — Bavarian architect.

Bavarian stucco artist

1709-1772 — Bavarian sculptor and decorator.

Prince-Bishop of Ottobeuren.

, one of the rare episodes of the Christian epic he chose to stage. What we see here goes counter to all that precedes it: gone from the scene are the dark-light essentiality, immobilism, silence and, above all, vital confidentiality between the viewer and the work. This work lives autonomously, exalting its own prowess, dancing and singing to its own glory.

Clearly, all the lines of this work progress upwards, towards the heights of Golgotha. The colors too - all the reds, blues, whites, golds, yellows, flesh colors in various shades - all progress upwards. The artist obviously enjoyed playing with space, producing something that is basically theatrical. In its contrast with the work of Caravaggio, Meylan, Guido Reni, van der Werff and Piazzetta, this painting serves as a masterful introduction to pictorial Rococo.

, one of the rare episodes of the Christian epic he chose to stage. What we see here goes counter to all that precedes it: gone from the scene are the dark-light essentiality, immobilism, silence and, above all, vital confidentiality between the viewer and the work. This work lives autonomously, exalting its own prowess, dancing and singing to its own glory.

Clearly, all the lines of this work progress upwards, towards the heights of Golgotha. The colors too - all the reds, blues, whites, golds, yellows, flesh colors in various shades - all progress upwards. The artist obviously enjoyed playing with space, producing something that is basically theatrical. In its contrast with the work of Caravaggio, Meylan, Guido Reni, van der Werff and Piazzetta, this painting serves as a masterful introduction to pictorial Rococo.

It also points the way to architecture: just as the Baroque paintings led us to the Il Gésu choir in Rome, so this painting by Tiepolo guides us to Rococo architecture, in particular as exemplified by Bavarian constructions. Here again, we will find ourselves far from the austere cult of the divine mystery. Instead, we will be confronted with works that translate a stylistic explosion accomplished with supreme mastery.

The 18th century

was the age of rocaille. It was also an era that witnessed the opening of frontiers, the first to become aware of what is now commonly termed "Europe". The 17th-century historical divisions of the Western world became a thing of the past, both culturally and politically, during the 18th century. Artists, musicians, men of letters, and the cultivated world in general all sought to erase national boundaries in order to achieve a European consensus in matters of taste. Since Rococo was in fashion during the 18th century, it became the first style to boast a "European" label.

At first, Rococo showed up above all in Venice, but hardly had it settled in there than it appeared in Northern Italy and, in no time at all thereafter, in France, from whence it spread all over Europe. In 1717, one of the fathers of rocaille/Rococo, the architect Filippo Juvarra In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)

Caravaggio

Georges de La Tour

Guido Reni

Adriaen van der Werff

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta

Rainaldi

Giambattista Tiepolo

Filippo Juvarra

Carl-Philip von Greiffenclau

Eugene of Savoy

Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt

Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer

Rupert Neß von Ottobeuren

Schmuzer (also spelled Schmuzzer and Schmutzer)

Johann Georg Bergmüller

Johann Jakob Herkomer

Franz Xaver Schmädl

Ignaz Günther

Dominikus Zimmermann

Anton Sturm

Johann Effner

Johann Michaël Fischer

Josef Weinmüller

Johann Michael Feichtmayr (the Younger)

Karl-Eugen von Greiffenclau

, undertook construction of the extraordinary

Basilica of Superga , on the outskirts of Turin. This basilica represents one of the first Rococo manifests. Only three years later (1720), the architect Johann Balthasar Neumann began building the "Residenz" (palace) of the Prince-Bishop Karl-Philippe von Greiffenclau, in

Würzburg.

, on the outskirts of Turin. This basilica represents one of the first Rococo manifests. Only three years later (1720), the architect Johann Balthasar Neumann began building the "Residenz" (palace) of the Prince-Bishop Karl-Philippe von Greiffenclau, in

Würzburg.

Thus, only three years separate the first Turinese model in this style and its - let us say Bavarian - application at Würzburg. This is striking proof of how open the national boundaries were during the 18th century. Again, four years later, and this time in Vienna, Prince Eugene (of Savoy) commissioned an enormous and ostentatious "Residenz" (palace). Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt

In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)

Thus, only three years separate the first Turinese model in this style and its - let us say Bavarian - application at Würzburg. This is striking proof of how open the national boundaries were during the 18th century. Again, four years later, and this time in Vienna, Prince Eugene (of Savoy) commissioned an enormous and ostentatious "Residenz" (palace). Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt

In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)

Caravaggio

Georges de La Tour

Guido Reni

Adriaen van der Werff

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta

Rainaldi

Giambattista Tiepolo

Filippo Juvarra

Carl-Philip von Greiffenclau

Eugene of Savoy

Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt

Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer

Rupert Neß von Ottobeuren

Schmuzer (also spelled Schmuzzer and Schmutzer)

Johann Georg Bergmüller

Johann Jakob Herkomer

Franz Xaver Schmädl

Ignaz Günther

Dominikus Zimmermann

Anton Sturm

Johann Effner

Johann Michaël Fischer

Josef Weinmüller

Johann Michael Feichtmayr (the Younger)

Karl-Eugen von Greiffenclau

, to whom he entrusted its construction, was one of the greatest architects of the period; he came up with a sort of double palace (upper and lower): the Belvedere . It was hence Hildebrandt who, in 1724, first brought the exuberant beauty of the Rococo style to Austria, a land whose frontiers now also stood open to this new language.

. It was hence Hildebrandt who, in 1724, first brought the exuberant beauty of the Rococo style to Austria, a land whose frontiers now also stood open to this new language.

In 1728, Margravine Wilhelmina of Bayreuth had the most beautiful theater of all of Europe built by the Galli de Bibienas, a family of architects and stage designers hailing from Northern Italy. No sooner was this Rococo jewel completed than similar theaters sprung up in respectively Dresden, Ulm, and Munich. In other words, the style spread like fireworks; all over Europe, it was copied and repeated. Even as far as Prague, where the architect Dientzenhofer undertook the Saint Nicholas Church of Mala Strana.

During the first half of the 18th century, Rococo passed on from the privileged sites of Venice and Turin to the furthermost ends of Europe: from Madrid to Prague, Naples to Tsarskoïe Selo, where Catherine the Great as well indulged her whims for several residences in utterly Rococo taste. Thus it can be said that truly all of Europe witnessed the cultural migration of what travelled under the aegis and emblem of Rococo.

Events

18th-Century Composers

1715: Death of Louis XIV

Dietrich Buxtehude —1637-1707 Elsinjoer, Lübeck

1715: Louis XV

Johann Krieger — 1652-1735, Nüremberg

1719: Defoe: Robinson Crusoe

Georg Muffat — 1653-1704, Megeve, Passau

1721: Montesquieu: Persian Letters

Johann Pachelbel — 1653-1706, Erfurt, Nüremberg

1722: J.S. Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier

Johann Nepomuk Fux — 1660-1741, Vienne

1730: Marivaux: Love in Livery

Franz Xaver Anton Murschhauser — 1663-1738, Alsace, Münich

1731: Abbé Prévost: Manon Lescaut

Johann Kaspar Ferdinand Fischer — 1670-1746, Rastatt, Bade

1734: Voltaire: Lettres Philosophiques

Johann Mattheson — 1681-1764, Hamburg

1740: Coustou: "Chevaux de Marly" group of statues

Johann Mattheson — 1681-1764, Hamburg

1745: Gluck: Ippolito

Johann Sebastian Bach — 1685-1750 Eisenach, Weimar, Leipzig

1746: Diderot: Pensées Philosophiques

Gottlieb Muffat — 1690-1770, Passau-Vienne

1749: Fielding: Tom Jones

Johann Ludwig Krebs — 1713-1780, Leipzig, Altenburg

1751: Encyclopedia I

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach —1714-1788, Leipzig, Potsdam, Hamburg

1754: Étienne Bonnot de Cadillac: Traité sur les Sensations

Johann Seger — 1716-1782, Bohême, Prague

1758: Jean-Jacques Rousseau - Lettre à d'Alembert

Georg Pasterwitz O.S.B. — 1730-1803, Kremsmunster, Passau

1762: Jean-Jacques Rousseau - The Social Contract

Johann Christian Kittel — 1732-1809, Erfurt

1763: Ange-Jacques Gabriel - the Petit Trianon (Versailles)

Frantisek Xaver Brixi — 1732-1771, Prague

1765: Jacques-Germain Soufflot - the Pantheon

Franz Joseph Haydn — 1732-1809, Vienne, Esterhaz

1767: James Watt - the steam engine

Joseph Lederer — 1735-1796, St Katharinenthal

1771: Gaspard Monge - analytic geometry

Johann Albrechtsbergere — 1736-1809, Klosterneuburg, Vienna

1773: Goethe - Goetz von Berlichingen

Jan Krtittel Vanhal — 1739-1813, Prague

1774: Death of Louis XV

Jan Krtittel Kuchar — 1751-1829, Prague

1775: Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais - The Barber of Seville

Justin Heinrich Knecht — 1752-1817, Biberach, Stuttgart

1778: Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon - Les Epoques de la Nature (in 5th vol. of 44 vols. "Histoire naturelle")

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart — 1756-1791, Salzburg, Vienne

1781: Rousseau - 1781 Rousseau: T

1782: Pierre Ambroise Choderlos de Laclos - Dangerous Connections

1783: Montgolfier bros./Pilâtre de Roziers' first balloon ascent

1785: The Marriage of Figaro

1785: Jacques-Louis David - Oath of the Horatii

1787: Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre - Paul et Virginie

1788: Foundation of "The Times"

1789: Antoine Lavoisier - Traité élémentaire de chimie

1789: Storming of the Bastille

At first, Rococo showed up above all in Venice, but hardly had it settled in there than it appeared in Northern Italy and, in no time at all thereafter, in France, from whence it spread all over Europe. In 1717, one of the fathers of rocaille/Rococo, the architect Filippo Juvarra In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)

Name

Role

Caravaggio (1571-1610). Michelangelo Merisi da, called Caravaggio after the town from which his family came. Italian painter who revolutionized pictorial tradition with strong contrasts accenting the vivid realism of his scenes. Greatly influenced the development of European painting.

1593-1652 — French painter renowned for the unmistakable originality of his style: skillfully organized plays of light, austere realism, simplified volumes.

1575-1642 - Italian (Bolognese) painter.

Disciple of Carracci.

1659-1722 — Dutch painter.

1683-1754 — Italian (Venetian) painter, who had great influence on Tiepolo.

1611-1691 — Italian architect of the High Baroque.

1696-1770 — Italian (Venetian) painter, decorator, and etcher. In his large-scale frescoes, the great clarity of color and deft draftsmanship make his figures seem to "fly" in airy space.

1678-1736 — Italian architect (Late Baroque and Early Rococo).

Prince-Bishop of Würzburg.

1663-1736 — Prince of House of Savoy, general in the service of the Holy Roman Empire, notredfor his patronage of the arts.

1668-1745 — Austrian architect

1689-1751 — Bohemian architect (Late Baroque), who worked mainly in Prague where he finished (great dome and bell tower,1737-1751) the St. Nikolas Church of Mala Strana (Little Quarter), started by his father in 1703, and built St. Nikolas Church of the Old Town Square 1732-6.

24. November 1670 in Wangen im Allgäu; † 20. Oktober 1740 in Ottobeuren; auch Rupert II war der 52. Abt und Reichsprälat des Klosters Ottobeuren.

Brothers Franz (1676-1741), decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph (1683-1752, architect and decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph's son Franz Xaver (1713-1775), decorator/stuccoer

1688-1762 — Bavarian painter, teacher, printmaker and draftsman.

1648-1717 — Bavarian architect, painter, and stuccoer.

1705-1777 — Bavarian sculptor.

1725-1775 — Bavarian architect and wood carver.

1685-1766 — Bavarian architect.

1690-1757 — Bavarian sculptor and stucco artist.

1687-1745 — Bavarian architect (Munich court architect) and decorator.

1691-1766 — Bavarian architect.

Bavarian stucco artist

1709-1772 — Bavarian sculptor and decorator.

Prince-Bishop of Ottobeuren.

, on the outskirts of Turin. This basilica represents one of the first Rococo manifests. Only three years later (1720), the architect Johann Balthasar Neumann began building the "Residenz" (palace) of the Prince-Bishop Karl-Philippe von Greiffenclau, in

Würzburg.

, on the outskirts of Turin. This basilica represents one of the first Rococo manifests. Only three years later (1720), the architect Johann Balthasar Neumann began building the "Residenz" (palace) of the Prince-Bishop Karl-Philippe von Greiffenclau, in

Würzburg.

Thus, only three years separate the first Turinese model in this style and its - let us say Bavarian - application at Würzburg. This is striking proof of how open the national boundaries were during the 18th century. Again, four years later, and this time in Vienna, Prince Eugene (of Savoy) commissioned an enormous and ostentatious "Residenz" (palace). Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt

In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)

Thus, only three years separate the first Turinese model in this style and its - let us say Bavarian - application at Würzburg. This is striking proof of how open the national boundaries were during the 18th century. Again, four years later, and this time in Vienna, Prince Eugene (of Savoy) commissioned an enormous and ostentatious "Residenz" (palace). Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt

In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)

Name

Role

Caravaggio (1571-1610). Michelangelo Merisi da, called Caravaggio after the town from which his family came. Italian painter who revolutionized pictorial tradition with strong contrasts accenting the vivid realism of his scenes. Greatly influenced the development of European painting.

1593-1652 — French painter renowned for the unmistakable originality of his style: skillfully organized plays of light, austere realism, simplified volumes.

1575-1642 - Italian (Bolognese) painter.

Disciple of Carracci.

1659-1722 — Dutch painter.

1683-1754 — Italian (Venetian) painter, who had great influence on Tiepolo.

1611-1691 — Italian architect of the High Baroque.

1696-1770 — Italian (Venetian) painter, decorator, and etcher. In his large-scale frescoes, the great clarity of color and deft draftsmanship make his figures seem to "fly" in airy space.

1678-1736 — Italian architect (Late Baroque and Early Rococo).

Prince-Bishop of Würzburg.

1663-1736 — Prince of House of Savoy, general in the service of the Holy Roman Empire, notredfor his patronage of the arts.

1668-1745 — Austrian architect

1689-1751 — Bohemian architect (Late Baroque), who worked mainly in Prague where he finished (great dome and bell tower,1737-1751) the St. Nikolas Church of Mala Strana (Little Quarter), started by his father in 1703, and built St. Nikolas Church of the Old Town Square 1732-6.

24. November 1670 in Wangen im Allgäu; † 20. Oktober 1740 in Ottobeuren; auch Rupert II war der 52. Abt und Reichsprälat des Klosters Ottobeuren.

Brothers Franz (1676-1741), decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph (1683-1752, architect and decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph's son Franz Xaver (1713-1775), decorator/stuccoer

1688-1762 — Bavarian painter, teacher, printmaker and draftsman.

1648-1717 — Bavarian architect, painter, and stuccoer.

1705-1777 — Bavarian sculptor.

1725-1775 — Bavarian architect and wood carver.

1685-1766 — Bavarian architect.

1690-1757 — Bavarian sculptor and stucco artist.

1687-1745 — Bavarian architect (Munich court architect) and decorator.

1691-1766 — Bavarian architect.

Bavarian stucco artist

1709-1772 — Bavarian sculptor and decorator.

Prince-Bishop of Ottobeuren.

. It was hence Hildebrandt who, in 1724, first brought the exuberant beauty of the Rococo style to Austria, a land whose frontiers now also stood open to this new language.

. It was hence Hildebrandt who, in 1724, first brought the exuberant beauty of the Rococo style to Austria, a land whose frontiers now also stood open to this new language.

In 1728, Margravine Wilhelmina of Bayreuth had the most beautiful theater of all of Europe built by the Galli de Bibienas, a family of architects and stage designers hailing from Northern Italy. No sooner was this Rococo jewel completed than similar theaters sprung up in respectively Dresden, Ulm, and Munich. In other words, the style spread like fireworks; all over Europe, it was copied and repeated. Even as far as Prague, where the architect Dientzenhofer undertook the Saint Nicholas Church of Mala Strana.

During the first half of the 18th century, Rococo passed on from the privileged sites of Venice and Turin to the furthermost ends of Europe: from Madrid to Prague, Naples to Tsarskoïe Selo, where Catherine the Great as well indulged her whims for several residences in utterly Rococo taste. Thus it can be said that truly all of Europe witnessed the cultural migration of what travelled under the aegis and emblem of Rococo.

For their constructions, the kings, emperors, or princes of the time could call upon the greatest artists; thus, for instance, Tiepolo

for Würzburg. Those who were not kings, not even princes, but who wanted to keep in step with the times anyway, were obliged to resort to the students of the greats, perhaps the students of the students, and so forth. The artists they commissioned were nomads with no fixed address for their workshops but who, travelling across Europe, were in the habit of renting out their services. Hence, it was thanks in large part to these itinerant artists that the Rococo style spread throughout Europe in quite coherent fashion, and due to them as well that the newly enriched upper classes would gradually acquire a taste for such an extravagant style.

for Würzburg. Those who were not kings, not even princes, but who wanted to keep in step with the times anyway, were obliged to resort to the students of the greats, perhaps the students of the students, and so forth. The artists they commissioned were nomads with no fixed address for their workshops but who, travelling across Europe, were in the habit of renting out their services. Hence, it was thanks in large part to these itinerant artists that the Rococo style spread throughout Europe in quite coherent fashion, and due to them as well that the newly enriched upper classes would gradually acquire a taste for such an extravagant style.

Due to Bavaria's geographic location, its roads became those most frequently travelled by these artistic nomads and, for some unknown reason, the village of Oberammergau

, at its center, their favorite stopover. Today, the facades of Oberammergau constitute one of the most extraordinary Rococo settings conceivable ... all in trompe l'oeil!

It would happen something like this: first we have the village. Secondly, a smoking room with cabbage soup wafting its delicious smell under the nose of a passing "skin-and-bones" figure, the itinerant artist. In his broken German, the artist proposes: "For a plate of soup, I'll paint you a window. For a week of sauerkraut, a façade. For a month's food and lodgings, the whole place!" As simple as that! Indeed, these artists could drum up quite a business for themselves, what with monumental staircases, balustrades, fake statues... The first to arrive were from Northern Italy, mainly the Piedmontese, followed by a generation of Tyrolians, and a third generation simply of Bohemians. This Piedmontese-Tyrolian-Bohemian conjunction is the origin of Rococo in northern Europe.

, at its center, their favorite stopover. Today, the facades of Oberammergau constitute one of the most extraordinary Rococo settings conceivable ... all in trompe l'oeil!

It would happen something like this: first we have the village. Secondly, a smoking room with cabbage soup wafting its delicious smell under the nose of a passing "skin-and-bones" figure, the itinerant artist. In his broken German, the artist proposes: "For a plate of soup, I'll paint you a window. For a week of sauerkraut, a façade. For a month's food and lodgings, the whole place!" As simple as that! Indeed, these artists could drum up quite a business for themselves, what with monumental staircases, balustrades, fake statues... The first to arrive were from Northern Italy, mainly the Piedmontese, followed by a generation of Tyrolians, and a third generation simply of Bohemians. This Piedmontese-Tyrolian-Bohemian conjunction is the origin of Rococo in northern Europe.

Having thus transformed an entire village, there was no reason these artists shouldn't work on the village church. After having served the bourgeoisie, why not serve the Lord? Hence, once the houses of Oberammergau , had been painted, attention turned to the village church. At a dizzying height above its high altar, some artist - undoubtedly Italian - painted a sort of pastiche of the baldachin (by Bernini) at St. Peter's Church of Rome. Thus Oberammergau, now boasting its own St. Peter's in miniature, could compare with the biggest basilica of the Christian world. And since this style inspired play with materials, the fresco was expanded to include sculpted wood and plaster decoration. These were in turn painted, so that, after some time, no one would be able to tell the real marble from the fake, the real fake marble from the fake real marble. And thus, gradually, illusionism began appealing not only to royal art patrons, but to the little villages of 18th-century Bavaria. From one end of Bavaria to the next, from the princes to the peasants, Rococo infiltrated the nooks and crannies of the land.

, had been painted, attention turned to the village church. At a dizzying height above its high altar, some artist - undoubtedly Italian - painted a sort of pastiche of the baldachin (by Bernini) at St. Peter's Church of Rome. Thus Oberammergau, now boasting its own St. Peter's in miniature, could compare with the biggest basilica of the Christian world. And since this style inspired play with materials, the fresco was expanded to include sculpted wood and plaster decoration. These were in turn painted, so that, after some time, no one would be able to tell the real marble from the fake, the real fake marble from the fake real marble. And thus, gradually, illusionism began appealing not only to royal art patrons, but to the little villages of 18th-century Bavaria. From one end of Bavaria to the next, from the princes to the peasants, Rococo infiltrated the nooks and crannies of the land.

How, one might wonder, could these little villages afford such luxury? The answer is twofold: In the first place, they were highly motivated. After centuries of religious unrest in Germany, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) somewhat structured the two main religions which, thanks to the treaty, managed to live more or less peacefully with each other. Thus there were provinces, principalities, even kingdoms and empires, that were fiercely Protestant, and others just as fiercely Catholic. Of the latter, Bavaria was the fiercest (still today, it staunchly defends Catholicism) and, as such, it sought to adopt the style celebrating that religion. Bavaria adopted Rococo in the manner one adopts a country, turning it into an emblem of both its faith and its patriotism. Secondly, and more pragmatically, 18th-century Bavaria was prosperous. Wise alliances had been forged there with the aristocracy and with the estate owners - in the main, convents and monasteries; also, the villages and property owners took a healthy stance towards money, so that Bavaria was able to get through the Westphalia Peace period without incurring the bankruptcy suffered by many of Germany's royal coffers. Hence, Bavaria was doing well for itself: a network of alliances, marriages, and a certain form of land speculation all combined to make its citizens rich - the princes, the abbots, the upper classes. Prince Karl-Philippe von Greiffenclau, to pick an example, who also held the title of bishop, was able to afford Würzburg , and to commission Tiepolo, clear across the world (that is, in Venice) for its decor. There was also the very wealthy abbot Rupert Neß of Ottobeuren, who undertook the renovation of the abbey church. Today the Ottobeuren Church

, and to commission Tiepolo, clear across the world (that is, in Venice) for its decor. There was also the very wealthy abbot Rupert Neß of Ottobeuren, who undertook the renovation of the abbey church. Today the Ottobeuren Church  is considered one of the most fabulous examples of rocaille style in all of Europe.

is considered one of the most fabulous examples of rocaille style in all of Europe.

The Wies village church, nicknamed die Wies. L'église die Wies , illustrates how the wealth of the upper classes, in this case unusually allied with the peasantry, contributed to the style's spread. In Wies, it was the monastery Steingaden and the farms that funded the church. In a period where the links with the monasteries were very close, the bourgeoisie knew just when the time was ripe to sell their lands, just as the peasants knew when it was ripe to buy them. Transaction by transaction then, the village became wealthy enough to treat itself to a church. No means were to be spared in the process, for they wished it to be the most beautiful and richest church of all.

Nor were any means to be spared in what it would take to attract people to church: the Cistercians of Salem built, at their own expense, the lovely Rococo church of Birnau, in the hopes of attracting a congregation from the neighboring town of Uberlingen, in order to sell them their surplus fruits, meat, and beer! Be that as it may, the result was the magnificent Church of Birnau.

, illustrates how the wealth of the upper classes, in this case unusually allied with the peasantry, contributed to the style's spread. In Wies, it was the monastery Steingaden and the farms that funded the church. In a period where the links with the monasteries were very close, the bourgeoisie knew just when the time was ripe to sell their lands, just as the peasants knew when it was ripe to buy them. Transaction by transaction then, the village became wealthy enough to treat itself to a church. No means were to be spared in the process, for they wished it to be the most beautiful and richest church of all.

Nor were any means to be spared in what it would take to attract people to church: the Cistercians of Salem built, at their own expense, the lovely Rococo church of Birnau, in the hopes of attracting a congregation from the neighboring town of Uberlingen, in order to sell them their surplus fruits, meat, and beer! Be that as it may, the result was the magnificent Church of Birnau.

Another example would be the religious community of Landsheim who, in a letter to the Bishop of Bamberg (a letter that truly exists!), claimed: "We are prepared to build a church right next to our fief, just outside on the uncultivated lands, a church so beautiful everyone will come to it! Thus we will honor both our Father and, by the same token, God. And we will attract so many people there. So we are ready to build such a church if you, Bishop of Bamberg, are willing to grant us the proceeds of the first ten years of church collections and profits." Vierzehnheiligen one of the most beautiful Rococo churches, is hence the fruit of negotiations between the Landsheim monks and the Bishop of Bamberg. As a final example, we have the monks of Andechs

one of the most beautiful Rococo churches, is hence the fruit of negotiations between the Landsheim monks and the Bishop of Bamberg. As a final example, we have the monks of Andechs , where a marvelous hop plant produced the best beer in all of Germany. Unluckily, there were no customers for it. What could be done with 2 million litres of beer a year? Build a pilgrimage church of course, and customers would flock in!

, where a marvelous hop plant produced the best beer in all of Germany. Unluckily, there were no customers for it. What could be done with 2 million litres of beer a year? Build a pilgrimage church of course, and customers would flock in!

So we see that not all these churches were erected in a strictly spiritual spirit. There is also a decidedly earthly aspect to what, once realized, came to represent among the most beautiful architectural settings, sculptures and wood carvings in the world. To put it simply, in Bavaria there is a marvel to admire every five kilometers!

for Würzburg. Those who were not kings, not even princes, but who wanted to keep in step with the times anyway, were obliged to resort to the students of the greats, perhaps the students of the students, and so forth. The artists they commissioned were nomads with no fixed address for their workshops but who, travelling across Europe, were in the habit of renting out their services. Hence, it was thanks in large part to these itinerant artists that the Rococo style spread throughout Europe in quite coherent fashion, and due to them as well that the newly enriched upper classes would gradually acquire a taste for such an extravagant style.

for Würzburg. Those who were not kings, not even princes, but who wanted to keep in step with the times anyway, were obliged to resort to the students of the greats, perhaps the students of the students, and so forth. The artists they commissioned were nomads with no fixed address for their workshops but who, travelling across Europe, were in the habit of renting out their services. Hence, it was thanks in large part to these itinerant artists that the Rococo style spread throughout Europe in quite coherent fashion, and due to them as well that the newly enriched upper classes would gradually acquire a taste for such an extravagant style.

Due to Bavaria's geographic location, its roads became those most frequently travelled by these artistic nomads and, for some unknown reason, the village of Oberammergau

, at its center, their favorite stopover. Today, the facades of Oberammergau constitute one of the most extraordinary Rococo settings conceivable ... all in trompe l'oeil!

It would happen something like this: first we have the village. Secondly, a smoking room with cabbage soup wafting its delicious smell under the nose of a passing "skin-and-bones" figure, the itinerant artist. In his broken German, the artist proposes: "For a plate of soup, I'll paint you a window. For a week of sauerkraut, a façade. For a month's food and lodgings, the whole place!" As simple as that! Indeed, these artists could drum up quite a business for themselves, what with monumental staircases, balustrades, fake statues... The first to arrive were from Northern Italy, mainly the Piedmontese, followed by a generation of Tyrolians, and a third generation simply of Bohemians. This Piedmontese-Tyrolian-Bohemian conjunction is the origin of Rococo in northern Europe.

, at its center, their favorite stopover. Today, the facades of Oberammergau constitute one of the most extraordinary Rococo settings conceivable ... all in trompe l'oeil!

It would happen something like this: first we have the village. Secondly, a smoking room with cabbage soup wafting its delicious smell under the nose of a passing "skin-and-bones" figure, the itinerant artist. In his broken German, the artist proposes: "For a plate of soup, I'll paint you a window. For a week of sauerkraut, a façade. For a month's food and lodgings, the whole place!" As simple as that! Indeed, these artists could drum up quite a business for themselves, what with monumental staircases, balustrades, fake statues... The first to arrive were from Northern Italy, mainly the Piedmontese, followed by a generation of Tyrolians, and a third generation simply of Bohemians. This Piedmontese-Tyrolian-Bohemian conjunction is the origin of Rococo in northern Europe.

Having thus transformed an entire village, there was no reason these artists shouldn't work on the village church. After having served the bourgeoisie, why not serve the Lord? Hence, once the houses of Oberammergau

, had been painted, attention turned to the village church. At a dizzying height above its high altar, some artist - undoubtedly Italian - painted a sort of pastiche of the baldachin (by Bernini) at St. Peter's Church of Rome. Thus Oberammergau, now boasting its own St. Peter's in miniature, could compare with the biggest basilica of the Christian world. And since this style inspired play with materials, the fresco was expanded to include sculpted wood and plaster decoration. These were in turn painted, so that, after some time, no one would be able to tell the real marble from the fake, the real fake marble from the fake real marble. And thus, gradually, illusionism began appealing not only to royal art patrons, but to the little villages of 18th-century Bavaria. From one end of Bavaria to the next, from the princes to the peasants, Rococo infiltrated the nooks and crannies of the land.

, had been painted, attention turned to the village church. At a dizzying height above its high altar, some artist - undoubtedly Italian - painted a sort of pastiche of the baldachin (by Bernini) at St. Peter's Church of Rome. Thus Oberammergau, now boasting its own St. Peter's in miniature, could compare with the biggest basilica of the Christian world. And since this style inspired play with materials, the fresco was expanded to include sculpted wood and plaster decoration. These were in turn painted, so that, after some time, no one would be able to tell the real marble from the fake, the real fake marble from the fake real marble. And thus, gradually, illusionism began appealing not only to royal art patrons, but to the little villages of 18th-century Bavaria. From one end of Bavaria to the next, from the princes to the peasants, Rococo infiltrated the nooks and crannies of the land.

How, one might wonder, could these little villages afford such luxury? The answer is twofold: In the first place, they were highly motivated. After centuries of religious unrest in Germany, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) somewhat structured the two main religions which, thanks to the treaty, managed to live more or less peacefully with each other. Thus there were provinces, principalities, even kingdoms and empires, that were fiercely Protestant, and others just as fiercely Catholic. Of the latter, Bavaria was the fiercest (still today, it staunchly defends Catholicism) and, as such, it sought to adopt the style celebrating that religion. Bavaria adopted Rococo in the manner one adopts a country, turning it into an emblem of both its faith and its patriotism. Secondly, and more pragmatically, 18th-century Bavaria was prosperous. Wise alliances had been forged there with the aristocracy and with the estate owners - in the main, convents and monasteries; also, the villages and property owners took a healthy stance towards money, so that Bavaria was able to get through the Westphalia Peace period without incurring the bankruptcy suffered by many of Germany's royal coffers. Hence, Bavaria was doing well for itself: a network of alliances, marriages, and a certain form of land speculation all combined to make its citizens rich - the princes, the abbots, the upper classes. Prince Karl-Philippe von Greiffenclau, to pick an example, who also held the title of bishop, was able to afford Würzburg

, and to commission Tiepolo, clear across the world (that is, in Venice) for its decor. There was also the very wealthy abbot Rupert Neß of Ottobeuren, who undertook the renovation of the abbey church. Today the Ottobeuren Church

, and to commission Tiepolo, clear across the world (that is, in Venice) for its decor. There was also the very wealthy abbot Rupert Neß of Ottobeuren, who undertook the renovation of the abbey church. Today the Ottobeuren Church  is considered one of the most fabulous examples of rocaille style in all of Europe.

is considered one of the most fabulous examples of rocaille style in all of Europe.

The Wies village church, nicknamed die Wies. L'église die Wies

, illustrates how the wealth of the upper classes, in this case unusually allied with the peasantry, contributed to the style's spread. In Wies, it was the monastery Steingaden and the farms that funded the church. In a period where the links with the monasteries were very close, the bourgeoisie knew just when the time was ripe to sell their lands, just as the peasants knew when it was ripe to buy them. Transaction by transaction then, the village became wealthy enough to treat itself to a church. No means were to be spared in the process, for they wished it to be the most beautiful and richest church of all.

Nor were any means to be spared in what it would take to attract people to church: the Cistercians of Salem built, at their own expense, the lovely Rococo church of Birnau, in the hopes of attracting a congregation from the neighboring town of Uberlingen, in order to sell them their surplus fruits, meat, and beer! Be that as it may, the result was the magnificent Church of Birnau.

, illustrates how the wealth of the upper classes, in this case unusually allied with the peasantry, contributed to the style's spread. In Wies, it was the monastery Steingaden and the farms that funded the church. In a period where the links with the monasteries were very close, the bourgeoisie knew just when the time was ripe to sell their lands, just as the peasants knew when it was ripe to buy them. Transaction by transaction then, the village became wealthy enough to treat itself to a church. No means were to be spared in the process, for they wished it to be the most beautiful and richest church of all.

Nor were any means to be spared in what it would take to attract people to church: the Cistercians of Salem built, at their own expense, the lovely Rococo church of Birnau, in the hopes of attracting a congregation from the neighboring town of Uberlingen, in order to sell them their surplus fruits, meat, and beer! Be that as it may, the result was the magnificent Church of Birnau.

Another example would be the religious community of Landsheim who, in a letter to the Bishop of Bamberg (a letter that truly exists!), claimed: "We are prepared to build a church right next to our fief, just outside on the uncultivated lands, a church so beautiful everyone will come to it! Thus we will honor both our Father and, by the same token, God. And we will attract so many people there. So we are ready to build such a church if you, Bishop of Bamberg, are willing to grant us the proceeds of the first ten years of church collections and profits." Vierzehnheiligen

one of the most beautiful Rococo churches, is hence the fruit of negotiations between the Landsheim monks and the Bishop of Bamberg. As a final example, we have the monks of Andechs

one of the most beautiful Rococo churches, is hence the fruit of negotiations between the Landsheim monks and the Bishop of Bamberg. As a final example, we have the monks of Andechs , where a marvelous hop plant produced the best beer in all of Germany. Unluckily, there were no customers for it. What could be done with 2 million litres of beer a year? Build a pilgrimage church of course, and customers would flock in!

, where a marvelous hop plant produced the best beer in all of Germany. Unluckily, there were no customers for it. What could be done with 2 million litres of beer a year? Build a pilgrimage church of course, and customers would flock in!

So we see that not all these churches were erected in a strictly spiritual spirit. There is also a decidedly earthly aspect to what, once realized, came to represent among the most beautiful architectural settings, sculptures and wood carvings in the world. To put it simply, in Bavaria there is a marvel to admire every five kilometers!

"Anyone who ever stood on the threshold of a rocaille-style church in ever so Catholic Bavaria was entitled to expect the strangest revelation.".

A short peek at each of the following six examples reveals one or another of their outstanding features:

- Ilgen - Wallfahrtskirche Mariä Heimsuchung

This small rustic ensemble was built in 1721 by an architect as unknown then as he has remained over the centuries, a certain Schmutzel. A master of rococo rusticity, Schmutzel excelled in particular at harmonizing colors. Here he used an off-white, an almost lemon yellow, and a caramel tone - shades that hardly go together, but that he managed to translate into an aesthetic effect bordering on a perversion of taste. The three colors are allowed to subtly interplay with each other, until they resolve into the ceiling of pure white. Schmutzel underscores the architectural and spatial impact of this field of white by leading up to it in a series of wreaths, mascaroons, cartouches, and strings of putti, all of which leave off at the wall tops. Upon entering this little church of Ilgen, we see how the surprising polychromatic harmony joins with the upward thrust of the vibrating wall elements and, in their resolution within the white of the ceiling, thus engaging our gaze in that direction. - Steingaden - Pfarrkirche Johannes der Taüfer

The decor here is more dynamic, turbulent, and surprising than any you might ever imagine. The colors - daringly pinker than to be found in the boudoir of a marquess, bluer than blue - are handled so dynamically it makes our eyes blink to look at them! The truth is that the artist, Johann Bergmüller In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)Name

Caravaggio Role

Caravaggio (1571-1610). Michelangelo Merisi da, called Caravaggio after the town from which his family came. Italian painter who revolutionized pictorial tradition with strong contrasts accenting the vivid realism of his scenes. Greatly influenced the development of European painting.Georges de La Tour 1593-1652 — French painter renowned for the unmistakable originality of his style: skillfully organized plays of light, austere realism, simplified volumes.Guido Reni 1575-1642 - Italian (Bolognese) painter. Disciple of Carracci.Adriaen van der Werff 1659-1722 — Dutch painter.Giovanni Battista Piazzetta 1683-1754 — Italian (Venetian) painter, who had great influence on Tiepolo.Rainaldi 1611-1691 — Italian architect of the High Baroque.Giambattista Tiepolo 1696-1770 — Italian (Venetian) painter, decorator, and etcher. In his large-scale frescoes, the great clarity of color and deft draftsmanship make his figures seem to "fly" in airy space.Filippo Juvarra 1678-1736 — Italian architect (Late Baroque and Early Rococo).Carl-Philip von Greiffenclau Prince-Bishop of Würzburg.Eugene of Savoy 1663-1736 — Prince of House of Savoy, general in the service of the Holy Roman Empire, notredfor his patronage of the arts.Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt 1668-1745 — Austrian architectKilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer 1689-1751 — Bohemian architect (Late Baroque), who worked mainly in Prague where he finished (great dome and bell tower,1737-1751) the St. Nikolas Church of Mala Strana (Little Quarter), started by his father in 1703, and built St. Nikolas Church of the Old Town Square 1732-6.Rupert Neß von Ottobeuren 24. November 1670 in Wangen im Allgäu; † 20. Oktober 1740 in Ottobeuren; auch Rupert II war der 52. Abt und Reichsprälat des Klosters Ottobeuren.Schmuzer (also spelled Schmuzzer and Schmutzer) Brothers Franz (1676-1741), decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph (1683-1752, architect and decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph's son Franz Xaver (1713-1775), decorator/stuccoerJohann Georg Bergmüller 1688-1762 — Bavarian painter, teacher, printmaker and draftsman.Johann Jakob Herkomer 1648-1717 — Bavarian architect, painter, and stuccoer.Franz Xaver Schmädl 1705-1777 — Bavarian sculptor.Ignaz Günther 1725-1775 — Bavarian architect and wood carver.Dominikus Zimmermann 1685-1766 — Bavarian architect.Anton Sturm 1690-1757 — Bavarian sculptor and stucco artist.Johann Effner 1687-1745 — Bavarian architect (Munich court architect) and decorator.Johann Michaël Fischer 1691-1766 — Bavarian architect.Josef Weinmüller Bavarian stucco artistJohann Michael Feichtmayr (the Younger) 1709-1772 — Bavarian sculptor and decorator., was familiar with painting: something that comes as no surprise, for he had worked as a local assistant to Tiepolo at Würzburg. Over the organ case (itself an incredible candy box in white and gold stucco), Bergmüller covered a large surface with a fresco depicting the creation of the Steingaden Church in the 8th century. It shows the Duke and the architect of Steingaden, and a plan of the church about to be remodelled. Strangely, the artist resorted to light and dark effects, leaving the construction site in darkness and the event itself, that is the Duke's acceptance of the construction plan, in such a light shade it almost conveys the idea of a miracle. Contrary to appearances, the wooden ramp between the organ case and the painting is not in the least architectural: it is pure illusionism. The artist was both clever and daring enough to distance the painting from the organ caseKarl-Eugen von Greiffenclau Prince-Bishop of Ottobeuren. by drawing a line - in this case, the ramp - between them. This depiction of a heavy wooden element, with dark shadows underneath it, is a manner of exorcising the organ case and enabling the motif to reappear a bit higher up, in the church's dedication ceremony.

by drawing a line - in this case, the ramp - between them. This depiction of a heavy wooden element, with dark shadows underneath it, is a manner of exorcising the organ case and enabling the motif to reappear a bit higher up, in the church's dedication ceremony.

- Ettal - Klosterkirche

The rich confessional booths here are beautiful enough to make you want to confess! Although the native Bavarian architect/decorator/stuccoer Joseph Schmuzer (in collaboration with his son Franz Xaver Schmuzer) was responsible for this church's restoration and redecoration in the late 1740s (due to fire damage), the confessionals were executed after his death, in time for the restored church's consecration in 1762. The stunning booths are carved out of a very rare and precious wood, above inlaid boxes of incredible beauty and inventiveness.

were executed after his death, in time for the restored church's consecration in 1762. The stunning booths are carved out of a very rare and precious wood, above inlaid boxes of incredible beauty and inventiveness.

- Füssen - Kloster St. Mangus

The stucco work in this tiny church, designed by Johann Schmindel In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)Name

Caravaggio Role

Caravaggio (1571-1610). Michelangelo Merisi da, called Caravaggio after the town from which his family came. Italian painter who revolutionized pictorial tradition with strong contrasts accenting the vivid realism of his scenes. Greatly influenced the development of European painting.Georges de La Tour 1593-1652 — French painter renowned for the unmistakable originality of his style: skillfully organized plays of light, austere realism, simplified volumes.Guido Reni 1575-1642 - Italian (Bolognese) painter. Disciple of Carracci.Adriaen van der Werff 1659-1722 — Dutch painter.Giovanni Battista Piazzetta 1683-1754 — Italian (Venetian) painter, who had great influence on Tiepolo.Rainaldi 1611-1691 — Italian architect of the High Baroque.Giambattista Tiepolo 1696-1770 — Italian (Venetian) painter, decorator, and etcher. In his large-scale frescoes, the great clarity of color and deft draftsmanship make his figures seem to "fly" in airy space.Filippo Juvarra 1678-1736 — Italian architect (Late Baroque and Early Rococo).Carl-Philip von Greiffenclau Prince-Bishop of Würzburg.Eugene of Savoy 1663-1736 — Prince of House of Savoy, general in the service of the Holy Roman Empire, notredfor his patronage of the arts.Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt 1668-1745 — Austrian architectKilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer 1689-1751 — Bohemian architect (Late Baroque), who worked mainly in Prague where he finished (great dome and bell tower,1737-1751) the St. Nikolas Church of Mala Strana (Little Quarter), started by his father in 1703, and built St. Nikolas Church of the Old Town Square 1732-6.Rupert Neß von Ottobeuren 24. November 1670 in Wangen im Allgäu; † 20. Oktober 1740 in Ottobeuren; auch Rupert II war der 52. Abt und Reichsprälat des Klosters Ottobeuren.Schmuzer (also spelled Schmuzzer and Schmutzer) Brothers Franz (1676-1741), decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph (1683-1752, architect and decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph's son Franz Xaver (1713-1775), decorator/stuccoerJohann Georg Bergmüller 1688-1762 — Bavarian painter, teacher, printmaker and draftsman.Johann Jakob Herkomer 1648-1717 — Bavarian architect, painter, and stuccoer.Franz Xaver Schmädl 1705-1777 — Bavarian sculptor.Ignaz Günther 1725-1775 — Bavarian architect and wood carver.Dominikus Zimmermann 1685-1766 — Bavarian architect.Anton Sturm 1690-1757 — Bavarian sculptor and stucco artist.Johann Effner 1687-1745 — Bavarian architect (Munich court architect) and decorator.Johann Michaël Fischer 1691-1766 — Bavarian architect.Josef Weinmüller Bavarian stucco artistJohann Michael Feichtmayr (the Younger) 1709-1772 — Bavarian sculptor and decorator., is on a par with what one could find in an imperial palace. This small room is enlarged by a fake balustraded floor, in turn occupied by strikingly imaginative figures representing the four parts of the world (West, Asia, Africa, and America). These four parts of the world are set on the four room quoins, above which cherubs have been painted as if supporting the ceiling. The ceiling, moreover, depicted as if in prolongation of the architecture, depicts a weathercock whose body corresponds with a gold arrow indicating another part of the world. What could be more illustrative of the illusionist science so in favor during the 18th century?Karl-Eugen von Greiffenclau Prince-Bishop of Ottobeuren. - Rottenbuch - Pfarrkirche Mariä Geburt

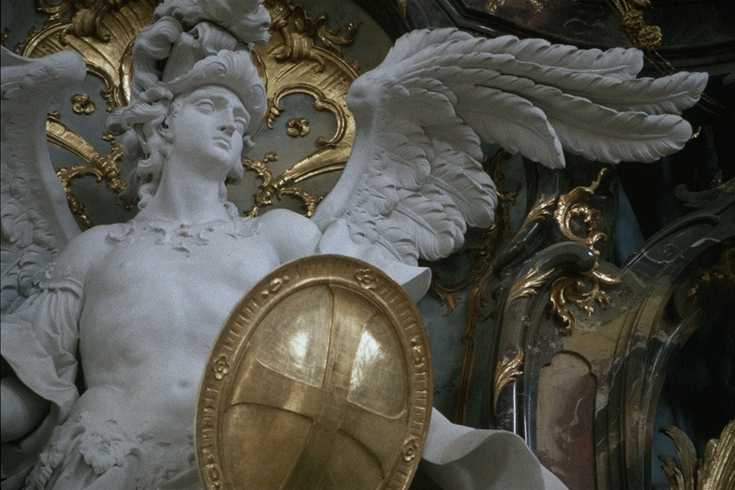

This church, redecorated by the stuccoer-decorator Joseph Schmuzer and his son Franz Xaver Schmuzer, boasts a particularly fabulous element: its stucco pulpit by Franz Xaver Schmädl (1747) is no doubt the most beautiful pulpit of Bavaria. A large angel guards the entry to it, while its balustrade is an outstanding example of marble and bronze trompe l'oeil. The figures of the four church Fathers, encircled by angels, are seated in the pulpit, and the entire arrangement dissolves into the pulpit canopy. The feeling is that the divine spirit breathes in this work, that the swoosh of its wings over the priest's head during mass puts the pom-poms and guirlands into sway.

is an outstanding example of marble and bronze trompe l'oeil. The figures of the four church Fathers, encircled by angels, are seated in the pulpit, and the entire arrangement dissolves into the pulpit canopy. The feeling is that the divine spirit breathes in this work, that the swoosh of its wings over the priest's head during mass puts the pom-poms and guirlands into sway.

- Weyarn - Stiftskirche St. Peter

The two sculptures to be seen in this church are particularly splendid examples of rocaille style. The wood carver Ignaz Günther In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)Name

Caravaggio Role

Caravaggio (1571-1610). Michelangelo Merisi da, called Caravaggio after the town from which his family came. Italian painter who revolutionized pictorial tradition with strong contrasts accenting the vivid realism of his scenes. Greatly influenced the development of European painting.Georges de La Tour 1593-1652 — French painter renowned for the unmistakable originality of his style: skillfully organized plays of light, austere realism, simplified volumes.Guido Reni 1575-1642 - Italian (Bolognese) painter. Disciple of Carracci.Adriaen van der Werff 1659-1722 — Dutch painter.Giovanni Battista Piazzetta 1683-1754 — Italian (Venetian) painter, who had great influence on Tiepolo.Rainaldi 1611-1691 — Italian architect of the High Baroque.Giambattista Tiepolo 1696-1770 — Italian (Venetian) painter, decorator, and etcher. In his large-scale frescoes, the great clarity of color and deft draftsmanship make his figures seem to "fly" in airy space.Filippo Juvarra 1678-1736 — Italian architect (Late Baroque and Early Rococo).Carl-Philip von Greiffenclau Prince-Bishop of Würzburg.Eugene of Savoy 1663-1736 — Prince of House of Savoy, general in the service of the Holy Roman Empire, notredfor his patronage of the arts.Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt 1668-1745 — Austrian architectKilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer 1689-1751 — Bohemian architect (Late Baroque), who worked mainly in Prague where he finished (great dome and bell tower,1737-1751) the St. Nikolas Church of Mala Strana (Little Quarter), started by his father in 1703, and built St. Nikolas Church of the Old Town Square 1732-6.Rupert Neß von Ottobeuren 24. November 1670 in Wangen im Allgäu; † 20. Oktober 1740 in Ottobeuren; auch Rupert II war der 52. Abt und Reichsprälat des Klosters Ottobeuren.Schmuzer (also spelled Schmuzzer and Schmutzer) Brothers Franz (1676-1741), decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph (1683-1752, architect and decorator/stuccoer, and Joseph's son Franz Xaver (1713-1775), decorator/stuccoerJohann Georg Bergmüller 1688-1762 — Bavarian painter, teacher, printmaker and draftsman.Johann Jakob Herkomer 1648-1717 — Bavarian architect, painter, and stuccoer.Franz Xaver Schmädl 1705-1777 — Bavarian sculptor.Ignaz Günther 1725-1775 — Bavarian architect and wood carver.Dominikus Zimmermann 1685-1766 — Bavarian architect.Anton Sturm 1690-1757 — Bavarian sculptor and stucco artist.Johann Effner 1687-1745 — Bavarian architect (Munich court architect) and decorator.Johann Michaël Fischer 1691-1766 — Bavarian architect.Josef Weinmüller Bavarian stucco artistJohann Michael Feichtmayr (the Younger) 1709-1772 — Bavarian sculptor and decorator., was one of the greatest geniuses of European Rococo (certainly on a par with Serpotta for Sicily). He was commissioned for some processional floats for Good Friday, two of which are still extant: The Annunciation and the Pietà. The AnnunciationKarl-Eugen von Greiffenclau Prince-Bishop of Ottobeuren. stands out for its daring imbalance, dramatic staging, and hanging folds, as well as for the emotion on the faces of its figures. Further qualities are its masterful beauty, and the magnificence of its polychromy. The unusual Pietà stages an enormous Christ and an unbelievably fragile Virgin, whose face is marked by a staggering Rococo emotional quality.

stands out for its daring imbalance, dramatic staging, and hanging folds, as well as for the emotion on the faces of its figures. Further qualities are its masterful beauty, and the magnificence of its polychromy. The unusual Pietà stages an enormous Christ and an unbelievably fragile Virgin, whose face is marked by a staggering Rococo emotional quality.

"Anyone who has spent any time in Bavaria will have noticed the strange and fierce pietism upheld by its citizens to this day."

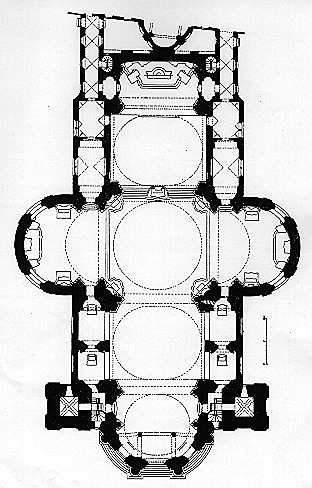

Two churches in particular have been selected for more detailed analysis: the Wies church as one of Bavaria's smallest and most intimate churches, and the Ottobeuren Church as one of its largest and most majestic.

"Gegeiselte Heiland" means the flagellation of Chirst. Why is this church located in the midst of pasture land? Why would such a marvel be found there? It could only be due to a miracle!

"Gegeiselte Heiland" means the flagellation of Chirst. Why is this church located in the midst of pasture land? Why would such a marvel be found there? It could only be due to a miracle!

In 1730, at the Steingaden monastery, preparations were underway for the Good Friday procession. Everyone with even the slightest talent worked on the famous processional floats to be paraded through the city, but two people worked harder than the rest: Reverend Father Magnus Straub and the lay brother Lukas Schweiger. These two participants were working on a beautiful representation of the flagellation; to make it seem truer to nature, the wood was stuccoed and leather was added. Touches of red paint were applied here and there, as were some dabs of blue and green to the wounds. When it was paraded on Good Friday in 1730, the resulting depiction was so true to life that it scandalized viewers with its terrifying realism.

By popular request, the lay brother was asked to put his flagellation of Christ in storage - anywhere would do, as long as he promised to keep it there! He decided to store it in the attic of his best friend, Jérémias Reele, the monastery innkeeper.

It so happened that the innkeeper's mother-in-law, who lived just a bit farther away, in the countryside (which, in Wies, consisted of three farms), came to visit him one day. Out of boredom, she decided to have a look at the attic, where she fell on her knees before the flagellated Christ. When it was time to leave, Maria Lory , as was her name, asked permission to take the Christ with her. Permission was granted, and she hauled her Christ on a little wooden cart all the way to Wies.

, as was her name, asked permission to take the Christ with her. Permission was granted, and she hauled her Christ on a little wooden cart all the way to Wies.

Up until this point, our story is merely anecdotal: it was transformed into far more when, eight years later, in 1738, a miracle took place. That year, on the 14th of June, Maria Lory looked up from her daily prayer to the Christ sculpture to see tears streaming down his face. The neighbours whom she excitedly called in to share in the experience bore witness to the fact that the Christ was indeed crying. The neighbors of the neighbors followed on their heels, and so forth, until a whole crowd, from as far as Steingaden, had gathered to witness the event. For many days thereafter, processions were organized and, of course, the Christ figure was transferred to the church in Wies.

Unfortunately, that church could hold only about fifteen people at a time, a state of affairs that inspired a decision by the Steingaden chapter to build a new church. In 1743, the monastery abbot Hyazinth Gassner proceeded to name those to be entrusted with realizing a setting for the Flagellation. In typical Bavarian style, he chose the best architect and the best sculptor to be had, respectively Dominikus Zimmerman and Anton Sturm Dominikus Zimmerman In the Main Roles (in order of appearance)

Caravaggio

Georges de La Tour

Guido Reni

Adriaen van der Werff

Giovanni Battista Piazzetta

Rainaldi

Giambattista Tiepolo

Filippo Juvarra

Carl-Philip von Greiffenclau

Eugene of Savoy

Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt

Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer

Rupert Neß von Ottobeuren

Schmuzer (also spelled Schmuzzer and Schmutzer)

Johann Georg Bergmüller

Johann Jakob Herkomer

Franz Xaver Schmädl

Ignaz Günther

Dominikus Zimmermann

Anton Sturm

Johann Effner

Johann Michaël Fischer

Josef Weinmüller

Johann Michael Feichtmayr (the Younger)

Karl-Eugen von Greiffenclau

had already proven his mastery throughout Bavaria, and was about to retire. Thus he was prepared to give his all to a last work he considered as a sort of spiritual bequest.

The first stone was laid on August 31, 1746. The dedication ceremony took place on September 2, 1749 - that is, only three years later! Thanks to a varied cast of actors - Maria Lory, Zimmerman, Sturm - the small church of Wies, set in the middle of the Bavarian countryside, was replaced by a magnificent and far larger one, all in white and lemon yellow.

The church is strangely shaped like a kidney: inside, the oval section serving to seat the worshippers is flanked on the left by the pulpit, and on the right by the choir loft.

is strangely shaped like a kidney: inside, the oval section serving to seat the worshippers is flanked on the left by the pulpit, and on the right by the choir loft.

The high altar , set to the rear, was built to Zimmermann's plans, and its design owes a great deal to Sturm. It serves as backdrop to the Flagellation at the origin of the new church. The interior as a whole is totally anti-Baroque, due to its oval shape with large openings, used by Zimmerman to allow light to burst forth from all parts and thus cancel all shadow. In Baroque architecture, shadow served to underscore the message of God, sole source of light; Rococo exorcises shadow in order to allow God's message to permeate the entire structure.

, set to the rear, was built to Zimmermann's plans, and its design owes a great deal to Sturm. It serves as backdrop to the Flagellation at the origin of the new church. The interior as a whole is totally anti-Baroque, due to its oval shape with large openings, used by Zimmerman to allow light to burst forth from all parts and thus cancel all shadow. In Baroque architecture, shadow served to underscore the message of God, sole source of light; Rococo exorcises shadow in order to allow God's message to permeate the entire structure.

Above the sources of light, a series of transverse arches (real and illusionist arches, in a spiral interplay of wide and recessed arches) seem to attain a most surprising formal frenzy. The fact is that Zimmerman resorted to everything he had ever invented here, in what he was leaving as a bequest to posterity. Thus the decor repeats all the architectural volumes: the paintings, sculptures, and bas-reliefs reiterate the perpetual motion afforded by contrasts between the church's concave and convex spaces.

The pulpit represents the prow of the Holy Spirit, one of the major Rococo formulas, and was executed in wood and stucco by artisans from the Benedictine abbey of Wessobrunn, on the basis of a plan submitted by Zimmerman. The big angel on the central part holds in check a deluge of gold- and silver-painted wood shells and swells that seems to engulf the putti in their midst.